25 September-1 October 2015 issue

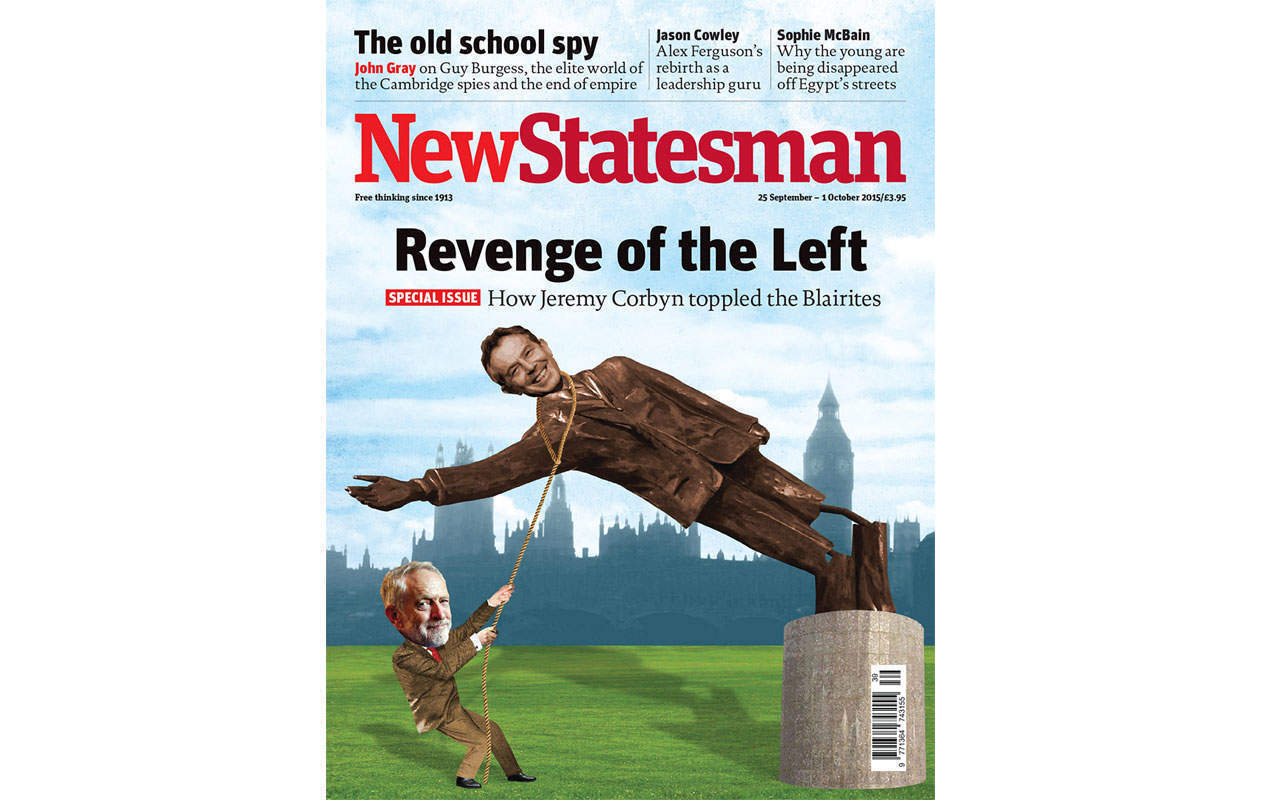

Special Issue: Revenge of the Left

Featuring

Exclusive Interview: Jeremy Corbyn on Trident, scrapping the benefit cap, a united Ireland, deselecting MPs, and the “brilliant” John McDonnell.

Tom Watson on a rocky first week as Labour deputy leader, Corbyn’s “stolen” lunches, how to offend Bananarama fans, and living in The Thick of It.

Jim Murphy: Corbyn, the SNP and the new era of post-truth politics.

Peter Kellner on the growing gulf between Labour’s target voters and the Corbynistas . . . and what Labour must do to win in 2020.

For the first time, Ed Miliband’s confidant Marc Stears on the trauma of election-night defeat and what has befallen the party since.

Nick Pearce on the crisis of the left and the disintegration of social democracy.

Helen Lewis: In May, Britain embraced austerity. But what happens when it starts hitting the sharp-elbowed middle class?

George Eaton speaks to Jeremy Corbyn in an exclusive – his first major interview since his election as Labour leader

On abolishing the benefit cap (after the shadow work and pensions secretary, Owen Smith, and the shadow equalities minister Kate Green insisted that party policy was to support a limit, not scrap the cap altogether):

“It’s what I’ve put forward as leader and I’ve made that very clear . . . We will now oppose completely the Welfare Reform [and Work] Bill. In my own constituency, the benefit cap has had the effect of social cleansing, of people receiving benefit but the benefit is capped; therefore, they can’t meet the rent levels charged and are forced to move. It’s devastating for children, devastating for the family and very bad for the community as a whole.”

On a united Ireland:

“It’s an aspiration that I have always gone along with.”

On whether unilateral nuclear disarmament would become Labour policy if a motion were approved at party conference:

“Well, it would be, of course, because it would have been passed at conference.”

[. . .]

“I understand the principles of dissent in parliament. I’ve expressed a bit of dissent myself in my time [he has voted against the party whip 534 times since 1997]. I respect that and I hope others will respect it, as well.”

On a senior serving general who told the Sunday Times that Corbyn would face a “mutiny” from the armed forces if he imposed severe defence cuts:

“I don’t know who this general was and apparently he’s been told off by his superiors already and I hope so. We live in a democracy and I think it’s surprising that somebody would make those kinds of statements. But, as I say, I don’t know who this person was, I don’t know the context in which the comments were made and I find it surprising that they haven’t been named.”

On Labour and mandatory reselection of MPs:

Corbyn has spoken out against mandatory reselection, the mechanism that some on the left of Labour hope to deploy to unseat right-leaning MPs, but he concedes that it would “absolutely” become “party rules” if activists voted in favour of the process at conference.

On a free vote for MPs on UK intervention in Syria:

“We haven’t reached that stage yet, because we don’t actually know what, if anything, the government is going to bring before parliament . . . Clearly, there may be differences of view and Ed Miliband went through the same experience and ended up with a fairly united position. I will obviously attempt the best unity I can get on this . . . My views on military interventions are very well known and they haven’t changed.”

On dealing with the media:

“I don’t expect any fair treatment from some of our media to me personally. That goes with the job. I have already said and will continue to say that I won’t respond to personal abuse and I never make any personal abuse, ever, to anybody. I just don’t do that kind of politics.

“What I find appalling is the intrusive nature towards my extended family.”

On Piggate:

Corbyn has “absolutely no response at all”.

Tom Watson: From stealing lunches to offending Bananarama fans – a rocky first week as Labour deputy leader

The NS Diary comes from Labour’s new deputy leader, Tom Watson. He reflects on his first days of serving under Corbyn in the eye of a media storm.

There are some things you just don’t see coming when you start a new job. Being accused of stealing food from war veterans . . . is one of them.

As readers might know, Jeremy Corbyn and I went to St Paul’s Cathedral on 15 September for a service to commemorate the Battle of Britain. Some enthusiastic young people who worked for Costa Coffee spotted our new leader as we were leaving and beckoned him over for selfies and a chat. We left with some sandwiches that they were handing out to guests.

It was a lovely moment and completely spontaneous but Jeremy got a rough ride in the press because he had allowed the staff to hand him two bags of food. The truth is that he did this because he was worried that his new government driver, who was taking him to Brighton to deliver a speech to the TUC, would miss his lunch. It was a typically thoughtful thing for Jeremy to do.

[. . .]

Peace broke out at Prime Minister’s Questions the following day, when there was a notable lack of hostilities across the despatch box. David Cameron was ill at ease with Jeremy’s crowdsourced questions. I felt anxious on the front bench, not least because Chris Bryant warned me repeatedly to stop fidgeting. But I felt the tension behind me dissipate once Jeremy got into his stride. The truth is that PMQs have become like The X Factor. Even MPs have developed a habit of judging their leader on his performance, rather than on the quality of his argument. I hope Jeremy can change that over the coming months.

[. . .]

Up early to do the Today programme. Angry Bananarama fans email and tweet their contempt after I compare the prospect of Labour MPs defecting to the Lib Dems with leaving the Beatles for a Bananarama tribute band. One tweet says it was no coincidence that I’d disparagingly compared the all-male Beatles to the all-female Bananarama. Do I issue a press release making it clear that I’m a Bananarama fan? You’d have to travel a long way to find a better pop song than “Robert De Niro’s Waiting”.

Jim Murphy: We live in a volatile age of post-truth politics – and so Brexit cannot be ruled out

The former leader of Scottish Labour Jim Murphy writes that while “Jeremy Corbyn may not have one drop of Scottish blood”, his campaign “was laden with learning from Scotland’s referendum.” Murphy explores what lessons from Yes 2014 and Jez We Can the organisers of the EU referendum could learn:

For the EU referendum, we have to come to terms with a politics in which wishful thinking can morph into a popular orthodoxy. The era of impeccably researched documents winning the day on their own is gone and gone for good.

Second, don’t pander to populism, because, unchallenged, it has an appetite that can never be satisfied. The Scottish Labour Party’s demise began with losing an argument it didn’t make a quarter-century ago.

[. . .]

Third, vote to remain but not to stay the same. Having powerful media allies and wealthy campaign backers is seductive but can also be harmful. In a politics where parts of England are tempted by eccentrics and Scotland by populists, it is deadly to be seen as an establishment fix.

[. . .]

Fourth, we have to convince early and convince often. I met very few people during Scotland’s referendum campaign who switched sides in the final hours.

[. . .]

Fifth, social media has at last started to deliver on the decade-old hype that it will help change politics.

Murphy concludes:

And one final thought. It will get personal. All campaigns attract an angry minority. But the other side’s minority will be bigger and fantastically noisier. The online treatment of the gutsy Liz Kendall as well as the bizarre anti-Semitism were vile. In Scotland, post-referendum passions are calming but remain strong. The greetings from strangers in the street sometimes still suggest that I’ve changed my first name to “Murphy” and my surname to “YaBastard!”.

That’s a different debate. And I’m going to put it down as just another example of post-truth politics.

Peter Kellner: The Corbyn insurgency has opened up a chasm on the left

Peter Kellner, president of YouGov, presents new data that shows how difficult it could be for Labour to win in 2020:

Successful party leaders marry the enthusiasms of their supporters to the mood of the wider electorate. By this test, Jeremy Corbyn looks destined to fail. Exclusive YouGov research for the New Statesman finds that the two groups are divided by a gulf that is unprecedented in modern British politics.

Those who voted for Jeremy Corbyn overwhelmingly describe themselves as left-wing. They reject capitalism, and they admire Tony Benn more than they admire Tony Blair. Two-thirds of them want to abolish private schools and the monarchy, and favour higher taxes to pay for greater welfare.

Labour’s target voters think none of these things. Nor do many current Labour supporters. The table gives the main findings. The first column sets out the views of those who voted for Corbyn to be party leader. The final three columns are taken from a separate survey of more than 10,000 electors. Currently, just over a quarter would vote Labour; a further 20 per cent would consider doing so. To win in 2020, Labour must retain the support of almost all its present supporters and at least half its potential voters.

Our figures show how hard this will be.

Marc Stears: The day the earth stopped

Ed Miliband’s confidant and former speechwriter Marc Stears recalls election night and the shock of defeat, and tries to make sense of what has happened since.

Conference season 2015 wasn’t meant to be like this, for any of us. The Conservatives were meant to be plunged into turmoil, having lost office. The Liberal Democrats were meant to be reimagining themselves as partners in a progressive alliance. The leading lights of a young Labour generation – Chuka Umunna, Tristram Hunt, Rachel Reeves and Liz Kendall – were meant to be getting used to their ministerial boxes. And I was meant to be writing a victory speech for a newly elected Labour prime minister.

Painful though it is to recall, it wasn’t that long ago that this alternative future disappeared. It was the night when the hope of 7 May turned to the despair of 8 May.

Only a few months later, Stears continues, it became clear that “the consequence of an election in which the British public opted for continuity was a landslide Labour leadership election victory for a candidate who promised to bring even bigger change” – Jeremy Corbyn.

Put this way, it is no wonder that there are many who genuinely care about Labour’s election prospects who are in despair. Within four months, we have had the public heading one way, followed by the party heading almost exactly in the opposite direction. It is not what any of my political scientist colleagues would describe as “orthodox vote-seeking behaviour”.

Stears writes that although Labour’s loss was a shock at first, now that “the dust has settled, I understand the [public’s] scepticism” of Ed Miliband:

Why should anyone who didn’t know Ed Miliband personally believe that he was sincerely trying to do things differently, trying to demonstrate that the words of political leadership should be dictated by the people? Why shouldn’t they just think it was a cheap trick in an otherwise standard party conference speech? Why should anyone think that a Labour government led by Ed would think differently from governments that had gone before?

These are the same questions that remain for Labour’s new leader. The ideology and policy orientation may have changed. The style may have changed even more. But it is going to take much more than either of those things to convince the British public that Labour has an approach to politics that respects them, that takes their lives seriously, that is sincerely concerned with changing the relationship between the governed and those who aspire to govern.

Stears, also a professor of political theory at Oxford, asserts:

The new leader, deputy leader and shadow cabinet need to display an inner belief that people matter more than politicians, that government doesn’t possess all the answers. They need to show they know that the trust that is crucial to our politics has snapped and needs to be restored. This means speaking boldly and directly to people’s concerns. It means forgetting the tendency to speak in the arcane abstractions of socialist politics; dropping the references to the International Labour Organisation and the long march of the working class. It also means an end to behaving as if all the conventions of public life apply only to others. It was the haughtiness behind the decision not to sing the national anthem at the Battle of Britain commemoration that was most off-putting of all. Even more importantly, it means turning decisively against the statism and the centralism of Labour’s past, both in terms of the party’s structures and its plans for government. Corbyn must be clear: the future is democracy, not dirigisme, experimental innovation, not narrow ideology.

Labour and the disintegration of social democracy

Nick Pearce, the outgoing director of IPPR, declares that Jeremy Corbyn’s “improbable leadership of the Labour Party is another symptom of the crisis of social democracy, not the incubator of its future”:

For although the left of the Labour Party is not a sect, it is sectarian. It inhabits a world-view, culture and practice of politics that is largely self-referential and enclosed. Save for brief moments of popular experimentalism – such as the two occasions when Ken Livingstone governed London – its reach has been minimal. Corbyn’s policy platform is an unreconstructed Bennite one, defined by nationalisation and reinstatement of the postwar settlement, given a fresh lease of life by revulsion at foreign wars and the social consequences of austerity. While his campaign tapped into discontent with the decrepit state of mainstream Labour politics, it did not give birth to a new social movement, rooted in popular struggle, like those that have sprung up in southern Europe.

Arguing that “social democracy is in crisis across Europe”, Pearce continues:

Britain’s first-past-the-post system has protected the Labour Party from the full force of these currents, but the pull of their logic is at work here, too: political loyalties have fractured, immigration has split the core working-class vote, and the financial crisis has ushered in a politics of economic security, not reform.

Pearce writes that, although it significantly broadened its electoral appeal in the New Labour era:

Labour has not created social and economic bases to replace those lost with the passing of industrial society. It has become caught in what the political scientist Peter Mair diagnosed as the trap facing all centrist parties: the one between responsibility and responsiveness. Parties aiming for elected office seek the patina of responsibility, fiscal and political. They set out credible, carefully crafted programmes for government, mindful of its constraints and compromises. Instead of representing the people to the state, they increasingly represent the state to the people.

He concludes that, even so, there are grounds for optimism on the centre left:

Economic reform, meeting the challenges of climate change and ageing, and the promise of digital technologies – all of these hold progressive potential. Social democracy could be just as well placed as any other tradition to capitalise on what the 2020s will bring; it doesn’t need to remain trapped between hollowed-out centrist technocracy and revanchist state socialism. But the depth of the crisis it faces demands deep and sustained rethinking, as well as political reorganisation. The rupture that Corbyn’s election has forced must be a catalyst for that change, or it will never come.

Helen Lewis: In May, the country embraced austerity. But what happens when it starts hitting the sharp-elbowed middle class?

For the Politics Column this week, Helen Lewis considers the potential effects of austerity politics on Britain’s middle classes. Although the public has been satisfied with austerity since 2010, the next five years will not be the same:

More of us will feel the pain, even though many believe the financial crash is long past and the worst is over. The Local Government Association, which represents English councils – most of which are Conservative-controlled – has warned that “popular” services will be affected. “Vital services, such as caring for the elderly, protecting children, collecting bins, filling potholes and maintaining our parks and green spaces, will simply struggle to continue at current levels,” its chairman, Gary Porter, newly ennobled to join the Conservative benches, said earlier this month.

Explaining how middle-class professionals such as lawyers and doctors will be hit by cuts to public services, Lewis notes that a shift in public opinion may be approaching. And she concludes:

George Osborne might find that his greatest achievement – cutting public services and still getting re-elected – is unrepeatable.