There is absolutely no elation. Mention the high likelihood of a Labour victory in an election next year to, say, the man charged with the party campaign, the highly experienced and disciplined Pat McFadden, and you’ll get a look back with all the cheery optimism of a drystone dyke in a hailstorm.

It is all caution, restraint, discipline. This year’s party conference, which begins in Liverpool on 8 October, will be even more decked in Union flags than last year’s but there will be no air-punching celebration, not the faintest whiff of Labour triumphalism. It’s all going to be about trying to persuade pessimistic voters that a change of government can improve their lives.

At the centre of that promise is growth. If taxes won’t rise, private sector investment becomes the last tool in the box. Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves, imposing even more stringent financial orthodoxy on the party, believe that simply having a dedicated, unflinching activist government, with plans for housing and green investment, will attract the money Britain desperately needs. Who knows – they face stiff competition.

[See also: The great crack-up]

Labour’s Treasury team has, I gather, also been looking at a long list of loopholes that they believe would generate billions of extra pounds, without raising tax rates. They don’t want to give away details because of the danger of the Conservatives swiping more of their policies. But a radical cleaning up of loopholes and allowances would be an obvious source of revenue.

To “close the deal”, Labour must persuade voters not simply that the last 14 years have been a failure but that real change is possible – to clean away some of our grubby national pessimism. But to do that without diverging from the fiscal orthodoxy is difficult. People close to Starmer talk of breaking the link between expenditure and radicalism and promise a list of practical reforms that would not require large front-loaded expenditure – from curriculum reform in education, to simplification of the planning system; a new-start housing policy with a bias towards first-time buyers; a better returns agreement with Brussels on migrants.

They do not talk about “the radical moment”, but about a government of security and rebuilding. And that indeed is where the public is now. Yet the critiques of Tory underfunding – schools, prisons, local government – will eventually have to be replaced by a positive, costed programme. One senior Labour figure described the danger ahead to me by paraphrasing Harry S Truman: “If the people are given the choice of two conservative parties, they will choose the genuine one.”

But for most of the political world, the great conundrum at the heart of this government-in-waiting is not policy specifics, but personality: Keir Starmer himself. Who is he, really? What, fundamentally, does he stand for? For a private and unrhetorical man, these are uncomfortable questions.

I do not share the general view that the reshuffle moved Labour to the “Blairite” right. As Jon Lansman of Momentum pointed out, that is hard to square with a big promotion for Angela Rayner, which, he said, “represents an important victory for her, for the left, and for the trade unions”.

The long-time party-watchers at the Labour Uncut website at least partly agree. They see Starmer more in the old pro-union Labour-right tradition of Ernest Bevin and Hugh Gaitskell than of Blairism. If, like Blair, he ends up arguing with unions over public sector reform, it will be because he wants better services, not because he believes more in the market than the state.

True, Pat McFadden, the most significant promotion, who now oversees Starmer’s road to power, was Blair’s political secretary. True, Liz Kendall, on the right of the party, takes a big role on work and pensions, and other Blairites such as Peter Kyle and Darren Jones have been moved up. But essentially, Starmer has been promoting people with experience who would help him get through the first months and years in power.

The people with experience are, by definition, the people who were there before. Since there are none left from the Callaghan government, then of course they are going to be veterans of the Blair and Brown years.

[See also: Tony Blair: “If I was back in front-line politics…”]

Tony Blair has been influential on Starmer, and they talk a lot – not about ideology but practicalities such as the technology revolution. Both men believe the politics of the 2020s to be very different from that of the 1990s. And they are fundamentally different: Blair was always political to his fingertips, delighting in shaping an argument; Starmer is driven not by creed or political philosophy but by how he can deliver practical change as fast as possible. He likes being out on the road, meeting people in different businesses, carrying the stories of crane drivers, or engineers, back to his office and working out plans to help. It’s a very different style of politics and most of us at Westminster are a bit baffled by it. What philosophers does he read? Which polemicists excite him? Um… As one ally puts it: “Keir has a lot of friends, but he doesn’t have a lot of friends in politics. He prefers to travel light.”

This makes him hard to place. Who Starmer “really is” matters. To win a majority he needs to be better understood, better liked. The Tories say, repeatedly, that “There’s no great warmth for him out there”, or “We don’t pick up any enthusiasm for Starmer himself”.

What else can they say, when no one thinks the Labour leader is extreme, dangerous, or has a hidden agenda? To fall back on the criticism that people don’t like him very much is – as they say these days – a bit meh. Yet if you look at the polling, it is not entirely made up: YouGov recently had 29 per cent saying they liked Starmer, but 37 per cent saying they disliked him. Redfield & Wilton’s recent “report card” poll, published on 1 September, is more positive, with a net 12 per cent positive rating for Starmer as a leader, against a minus 15 per cent rating for Rishi Sunak.

We will learn more about Starmer the man next year when the first biography – written with his close cooperation by Tom Baldwin, a journalist and former senior adviser to Ed Miliband – comes out. But a working hypothesis might be that, in a political culture reliant on handy, crude class identities, Starmer simply does not fit in. Sir Keir, with his southern accent and sober suits, doesn’t look or sound working class to most people. He is not posh. So, what is he? Not being sure can make people less likely to form an emotional connection.

As one of his allies puts it, Starmer has a very complicated relationship with class. Coming, famously, from the working-class parentage of toolmaker and nurse, he broke through by hard work to become a lawyer and then director of public prosecutions. (At the despatch box, he doesn’t paint visions in the air: he prosecutes.) Thus far, it’s a straightforward British story of graft and aspiration.

But class matters deeply to Starmer, as his recent speech on state education and breaking the “class ceiling” demonstrated. His shadow cabinet is as working class as any I can remember. Could that be because not all members of his family emerged into the smooth, well-spoken professional world as he did? His three siblings are a carer, a mechanic and a dinner lady. And anyway, if you are working class in a Surrey village, are you really “working class”, as traditionally understood, at all? You don’t have the kind of community or collective that a working-class child would have in the West Midlands or Glasgow. You talk southern, which to much of the country sounds like posh.

Compare the self-confident authenticity of Angela Rayner, Bridget Phillipson, John Prescott or – though his case is also complicated – Wes Streeting. They have all suffered moments of impostor syndrome; I don’t think Starmer ever has. It’s as if we have a national class jigsaw and the Starmer piece isn’t the right shape to fit into the picture.

The deeper criticism is that he “flip-flops” or – for the left – that he’s ditched so many promises. But unpick this, and all it means is that he has done everything needed to take Labour in short order from unelectable to government-in-waiting. For true Conservatives and for the hard left, this is simply unforgivable. They’d both much prefer him to be failing in a principled manner.

Personally, he is a principled and moral man. Add in his dislike of politics as a game; his preference for flying solo, rather than as part of a political club; and a powerful streak of hyper-competitiveness. Add, finally, his absolute refusal to use his own family for political advantage, and that he came late to politics… and the confusion about him is hardly surprising.

I think he would make a far better prime minister than a party leader. People who work closely with him say that his most powerful quality is his temperament. He doesn’t agonise about personal slights or hostile newspaper coverage. They say that compared to other political leaders he has remarkably little ego; that he is ready to give others the credit, and is calm about his personal status.

All very creditable – but voters remain unsure. There is probably nothing to be done about that. Attempts by Keir Starmer to change his style or alter his way of speaking would be met with a McFadden-like stare. We will only start to know who he really is once he’s in power. The trouble is, that uncertainty about him may be a serious road-bump on the way.

[See also: Culture is everything – and if Labour is to win us over, it needs to rediscover its own]

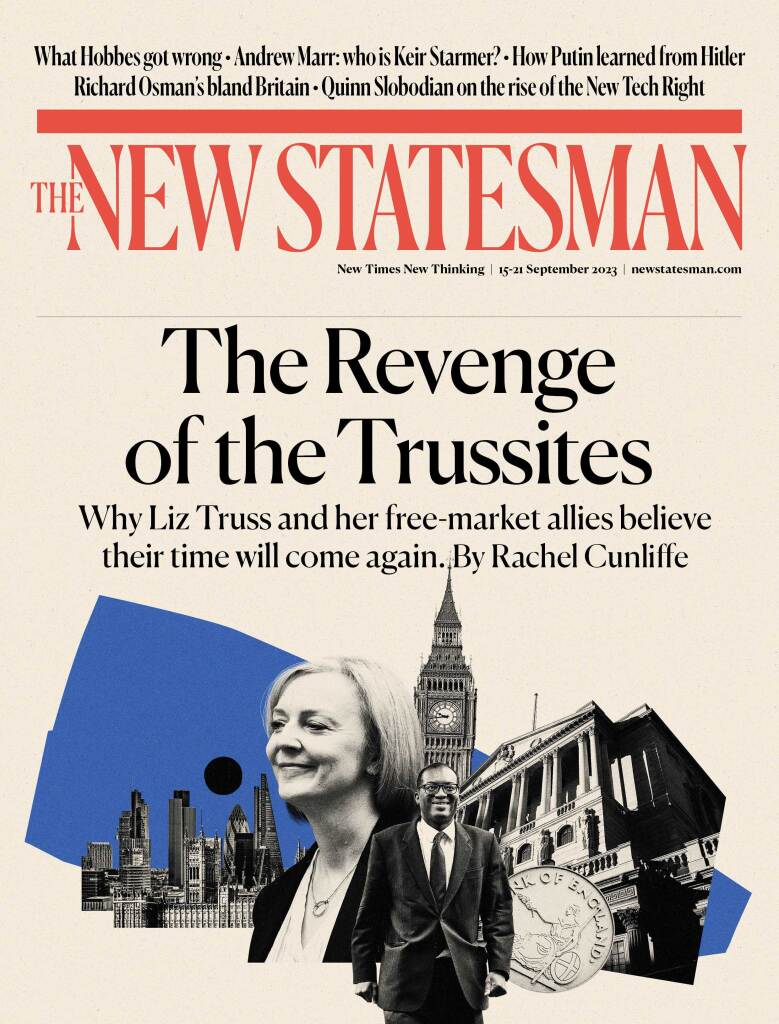

This article appears in the 13 Sep 2023 issue of the New Statesman, The Revenge of the Trussites