What makes a person want to be a journalist? Dmitry Muratov, editor-in-chief of the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, knew he wanted to be a reporter early on, a conviction that came to him after the visit of three famous ice hockey players to the closed city of Kuibyshev (now Samara), where he grew up. When these stars refused to give him and his friend an autograph, his mother wrote an indignant letter to a newspaper, a move that eventually resulted in the miraculous arrival of some signed photographs in the post. Amazed by the journal’s power, Muratov vowed then and there that he would one day work at such a place himself.

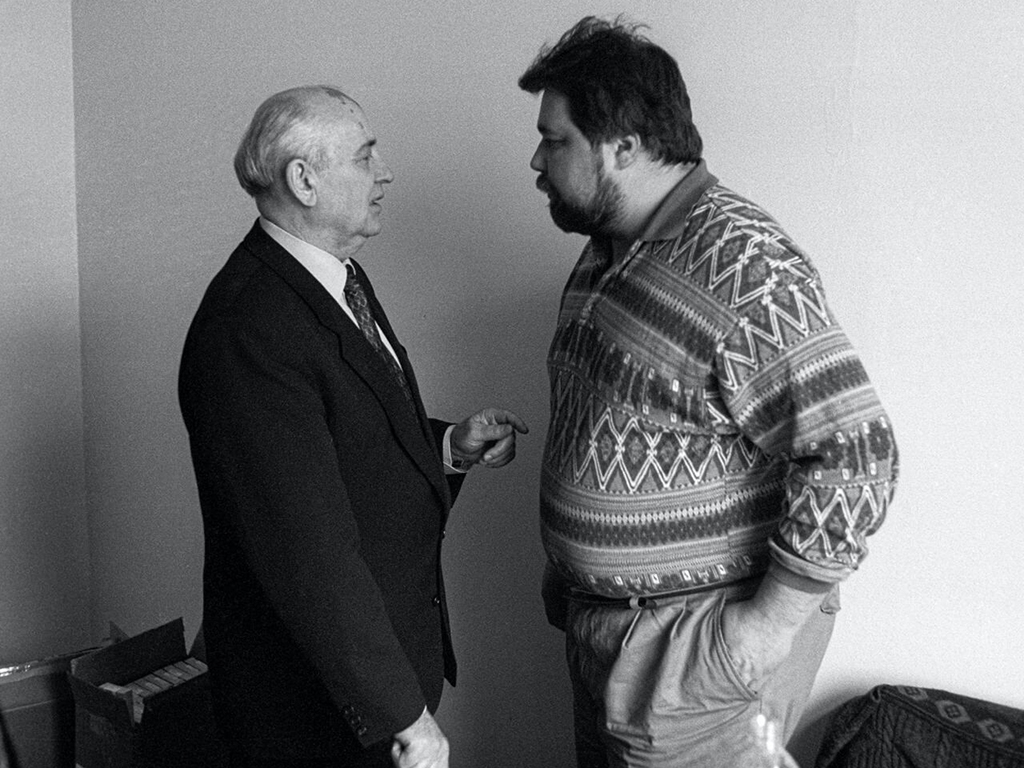

And so he does. Muratov and a group of colleagues established Novaya Gazeta in 1993, its mission to investigate corruption, human rights violations and other abuses of power; he has been its editor for more than two decades. But can a newspaper still be powerful in a country where the press is no longer free? Novaya is not currently published in Russia; following Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the situation for its journalists, already dangerous, has become perilous. Muratov continues to live in Moscow in spite of the risks, but many of his staff now operate from Riga, in Latvia, under the eye of Kirill Martynov, a man whose phlegmatic calm is almost as awe-inspiring to me as that of his ultimate boss.

The Price of Truth, a documentary made by Muratov’s friend, the film-maker Patrick Forbes, follows him through 2022 and into 2023, a period in which a lot – too much – happens. The invasion begins in February. For a while, Muratov stays ahead of the censorship and the threats (journalists deemed “foreign agents” receive long prison sentences). But by April, it’s beginning to be too much. He is attacked on a train by a “veterans’ group”, red paint and acetone thrown over him, burning his eyes. The newspaper’s move to Riga is made. By May, the first new iteration of Novaya has been published – put together, as Martynov puts it, by a load of “people sitting on suitcases”.

In June, Muratov sells his Nobel Peace Prize medal, awarded in 2021 for his efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, at a New York auction for $103.5m, the money to be used to help Ukrainian child refugees. In August, his friend Mikhail Gorbachev dies, a painful loss, and one heady with symbolism. Finally, there is the violent beating of Elena Milashina, one of Muratov’s star journalists, in Chechnya in July 2023. Muratov travels to Grozny to accompany her back to Moscow. On the plane, we see him tenderly cutting up Milashina’s dinner, her bandaged hands too battered for the job.

All of this is chastening. Drinking tea at my desk, I feel a combination of admiration and something close to shame. Muratov’s bravery and determination make my own small battles seem so pathetic; he’s a hero to me. But the film is enlightening, too. Muratov has a strangely poetic way with words, and for this reason, what he has to say about events in Russia stays with you in a way reports on the BBC News at Ten do not, for all that I’m devoted to Steve Rosenberg. What’s going to happen? Forbes asks him. “There’s no happy ending,” replies Muratov, as bewildered by Putin’s invasion of Ukraine as anyone else. The president, he says, is “thinking about how to change the past”, a phrase that might have come straight out of Lewis Carroll.

Propaganda is like radiation, he tells us: toxic, but invisible until it’s too late. “You sow doubt,” a judge tells him, about to shut down Novaya on some technicality. His line makes Muratov smile, for isn’t this what journalists are supposed to do? Isn’t it our job to pull on a hazmat suit and tackle the noxiousness? In a startling encounter at a press conference with Putin – it’s a scene from a movie – Muratov complains of the arbitrary moves against journalists, likening the situation to the beheading of Milady in Alexandre Dumas’s novel, The Three Musketeers (I told you he was poetic). Putin’s response is almost artful in its straightforwardness, its smooth avoidance of any outright lie. “No one is beheading anyone,” he says, his face stretched tight with some other poison, his manner that of a sinister psychiatrist towards a particularly hysteric patient.

The Price of Truth

Channel 4, 21 August, 10pm

This article appears in the 23 Aug 2023 issue of the New Statesman, Inside Britain’s Exclusive Sect