Social media giants should repay the British public for money lost to fraudulent advertising seen on their websites, the chair of parliament’s digital, culture, media and sport select committee has said.

Julian Knight was quizzing representatives from Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and TikTok about online safety in an evidence session in parliament this week.

The session was in preparation for the Online Safety Bill, which is making its way through parliament and will subject tech platforms to fines, restrictions and possible criminal liability if they do not protect their users from harmful and illegal content.

Online fraud is rife and has surged during the pandemic, with more than £2.3bn estimated to have been lost by consumers to cyber scams between April 2020 and April 2021. This figure is based on reported crimes, so the true figure is likely to be much higher. Last year, Ofcom, the UK’s communications regulator, also found that scams and data hacking are the biggest concerns for UK adults around using the internet.

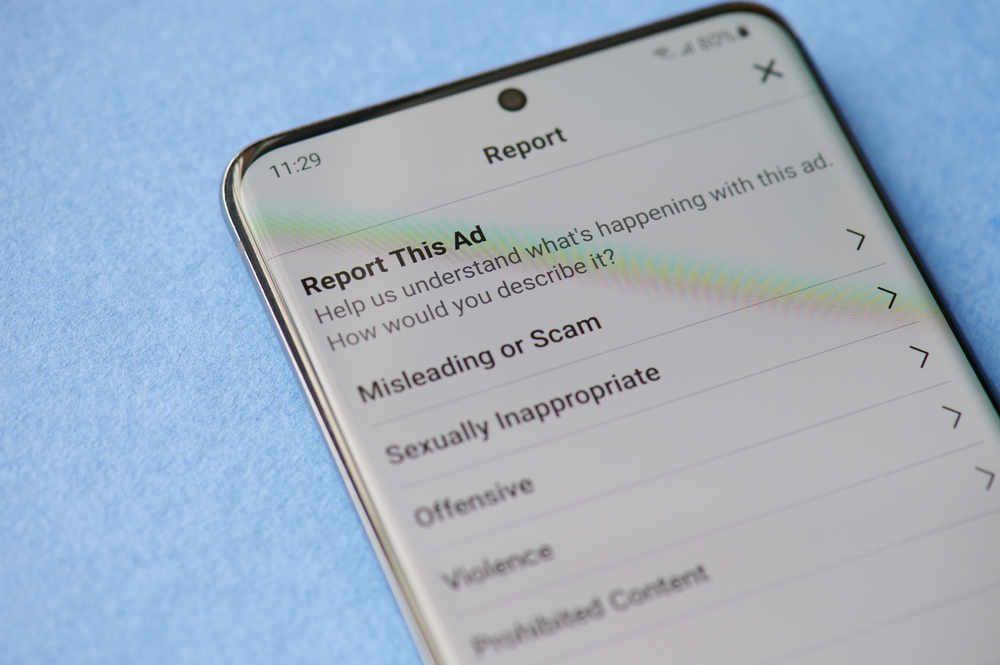

One form of online fraud tricks consumers through fake adverts, which either carry endorsements from celebrities, promote products for sale on fake websites, or promote schemes that offer early access to pension pots or cryptocurrencies. The identity of Martin Lewis, founder of Moneysavingexpert.com, has frequently been used without his consent to promote scams, and he has lobbied government on this issue.

[See also: What the Online Safety Bill means for social media]

In parliament, Knight called for better regulation and oversight by social media giants over who can advertise on their platforms and asked why they needed to wait for new legislation “to do the right thing and stop people being robbed blind by a collection of fraudsters”.

He added that people had not only lost thousands of pounds to scams but in some cases their livelihoods and their lives, referring to people who have died of suicide.

Only financial services firms authorised by the regulator the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) should be able to advertise on social media sites, he said, adding that this should have been enforced years ago.

“For many years, you’ve taken money from these scam artists,” he said. “The one thing you could [have done] to stop this was to prevent anyone who was not FCA-authorised advertising with you. Personally, I think that’s a disgrace and it’s been going on far too long. You ought to pay back the money defrauded from the British public.”

Richard Earley, UK public policy manager at Facebook, said he “didn’t accept” that his company was doing nothing to stop scams. Facebook, Microsoft and Twitter announced at the end of 2021 that they would now only allow financial services adverts from FCA-backed companies.

He said the platform already has technology in place to identify and remove scam ads and has its own strict advertising compliance policies.

“You’re absolutely right that the use of the internet to try to carry out fraud is a really serious problem,” he said. “We’re not waiting for legislation to act. One of the big challenges we face is that fraud and advertising scams are designed to be difficult to tell apart from authentic advertising.”

The chair of the FCA, Charles Randell, has also spoken out on this issue, calling out Google in particular; in 2020, he said there needs to be a framework to stop social media platforms and search engines from promoting scams, adding that the regulator currently pays for warning ads to counteract the impact of fraudulent ones.

“It is frankly absurd that the FCA is paying hundreds of thousands of pounds to Google to warn consumers against investment advertisement from which Google is already receiving millions in revenue,” he said.

[See also: Cyber-flashing is sexual harassment and must be made illegal, demand MPs]

Illegal content and child abuse

The four tech giants at the evidence session were also quizzed on how they are addressing illegal content, such as child sexual abuse and exploitation.

All four platforms said they had detection and removal tools in place, with Earley adding that Facebook has made its detection algorithm “open source” – freely available for other platforms to use.

Iain Bundred, head of public policy at YouTube, said that the platform is working hard to remove this “abhorrent material”, while Niamh McDade, deputy head of UK policy at Twitter, noted the importance of platform collaboration to tackle this issue. “We don’t want bad actors to be pushed off one platform and end up on another,” she said. Elizabeth Kanter, director of government relations UK at TikTok, spoke about tools in place to stop under-15s interacting with strangers, such as restrictions on direct messaging.

Anonymity and online hate speech

McDade was asked about the danger of anonymous accounts on Twitter, particularly those that send racist abuse. John Nicolson, SNP MP and committee member, said that the platform’s identity verification process, which requires a date of birth and either a contact number or email address to create an account, was “deeply flawed”.

She responded that there was “no place for racism on Twitter” and that tackling online abuse is a “priority”, but also that the platform wants to protect anonymity.

“We want to protect the ability to use a pseudonym across the platform,” she said. “Using a pseudonym does not always equal abuse, just as using a real name does not always indicate someone not being abusive.”

Watch the parliament session in full here.

[See also: What’s illegal offline must be illegal online, says Damian Collins]