Let’s face it – the hallowed US comedy show Saturday Night Live, while always weirdly watchable, has never been very funny. And its least funny cast member of all time was Robert Downey Jr, who spent a season in the mid-1980s floundering on the small screen, even as his Hollywood career was taking off. But I always liked Downey Jr and found his later performances in films such as True Believer compelling, in large part because of his awkward physicality. There was a sense of in-between about him. He was both vulnerable and confident, subtly camp.

His breakthrough role came in 1987’s Less Than Zero, in which he played a strung-out drug addict. Downey Jr is, of course, now best known as Iron Man. Fitness websites and magazines analyse his workout routines and diet: “With his five-day weight training programme… he gained more than 20 pounds of muscle,” bodybuilding.com reports. But for me, he shone most brightly as a star when he looked jacked-up, not jacked – when people thought he was attractive because he was a danger to himself, rather than a danger to world-conquering supervillains. It’s an unhealthy result of my adolescence in the 1990s, I suppose, when “heroin chic” was a thing, and waifish, skinny boys like Brett Anderson somehow became pin-ups. Today, even Ben Stiller is hench.

Street Fashion: Jock from the series Gay Semiotics (1977/2016) by Hal Fischer

I mention all this because what often gets lost in discussions about masculinity is that the ideal man periodically regenerates, like Doctor Who. He’s an archetype that changes with the times. Over the past couple of decades, the mainstream went from laughing at Peter Andre’s six-pack to aspiring to Chris Hemsworth’s; lads’ mags went extinct and #MeToo brought in a new consciousness about male abuses of power. What does the ideal man look like in 2020?

A new photography show at the Barbican claims to consider “how masculinity has been coded, performed and socially constructed”, but it sidesteps this issue somewhat. “Masculinities” devotes little space to the mainstream culture that did (and does) all of that coding and constructing – no shots from men’s magazines here; no clips of, say, Burt Reynolds in his hairy-chested prime. Instead, it focuses on critical responses to this phantom hegemonic power, under the assumption that everyone is on the same page of a well-thumbed copy of Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble. More nuance on conventional assumptions about masculinity would have been welcome.

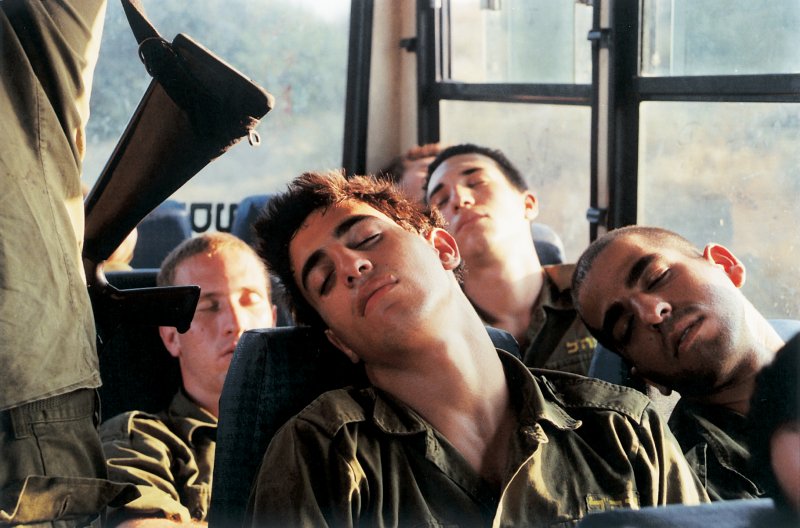

An untitled photograph from Adi Nes’s series Soldiers (1999)

However, as a survey of dissenting (or at least questioning) voices, “Masculinities” is well structured and, at times, even thrilling. Upon entering, I was confronted with John Coplans’ Self-Portrait (Frieze No 2), a startling set of four panels, each containing three close-up images of the then 74-year-old British artist’s body. Rousseauvian in its honesty, it’s all sagging flesh, pubes and wrinkles, yet beautiful, too, full as it is of the awful daring of utter surrender. Opposite, I read a quote from the civil rights activist James Baldwin characterising “the American ideal” of masculinity as “paralytically infantile” and unable to accept the “complexity of manhood” – surely still a primary cause of the traumas and depressions facing dudes in the comfortable West.

Then I looked at some images of Lebanese soldiers taken by the photographer Fouad Elkoury during the 1975-90 civil war. Performing to the camera, they stand purposefully in the way we expect soldiers (and, frankly, all men) to. Only two of the six soldiers smile. Contrasted with these were photographs by Adi Nes, showing Israeli troops at their most unguarded. In an untitled picture, four men shoot the breeze in a tent, one of them playing with a candle – he’s got wax all over his hands. I was moved by the tenderness of the scene, the absolute lack of purpose in it.

Peter Hujar’s David Brintzenhofe Applying Makeup (II) (1982)

And so the show took me seamlessly from wartime posturing to cowboys, then from visceral portrayals of physical functions (crying, pissing) to the rites and rituals of Yale frat boys, and on and on through images of political power, fatherhood and misogyny. It’s an impressive work of curation, though the decision to physically marginalise the excellent sections on black bodies, the female gaze and queer culture to the floor above is a shame – especially since the polemical purpose of this show seems to be to demonstrate that gender signification is a kind of language. No work here does that better than Hal Fischer’s Gay Semiotics, which humorously catalogues the sartorial “signalling devices” employed in the San Francisco gay scene. Nonetheless it’s a brilliant exhibition, if what you want is a summary of the poststructuralist argument for gender performativity. It doesn’t quite explicate the male condition – but not even Robert Downey Jr is capable of that.

“Masculinities” runs until 17 May

Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography

Barbican Art Gallery, London EC2

This article appears in the 04 Mar 2020 issue of the New Statesman, Inside No 10