There is a subgenre of comment article that has been flourishing since the financial crash in 2008, its central conceit summed up in the agonised question: “Where has all the protest music gone?” Depending on the age and personal taste of the author, Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan, or the Clash and the Sex Pistols, or the Specials, Billy Bragg and Red Wedge will be cited as having captured the zeitgeist of a more sincere and selfless time, when musicians used their guitars (they were usually men with guitars) as weapons against injustice, singing earnest political songs that yearned for freedom and a better tomorrow. The flip side to this construction of a western canon of worthy political music is the sense that anything outside of it – especially contemporary pop music – is shallow and mindless, devoid of political meaning.

Having worked for music and youth culture magazines and also as a foreign correspondent, Matthew Collin has the perfect CV to explode this narrow definition of political music and, in this entertaining collection, he combines original reporting from the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s with the wisdom of hindsight. His account spans drug-addled free festivals in central Europe and the Balkans, the use and abuse of disco as “soft power” in South Ossetia, the Berlin Love Parade, the Gezi Park uprising in Turkey, Public Enemy and rock as resistance in contemporary Russia. As a participant-observer in this admittedly strange assembly of countercultural moments, Collin has a zeal that’s a tonic to the weary scepticism of armchair critics. When he begins a recollection with the phrase “My notes that day are a rambling, somewhat intoxicated essay . . .” it’s endearing rather than off-putting.

Although the opening chapter on Public Enemy is a little overfamiliar (Chuck D having entered the rock canon along with Joe Strummer and Dylan), the less well-known characters whom Collin meets on his travels are gloriously compelling. Chief among them is Keith Robinson – half Sudanese, part Viking, a fearless techno evangelist surrounded by wastrels “from the outer limits of the lysergic frontier”, a young Scot who threw his first illegal rave in a disused bank in Glasgow in 1991, plastered it with pictures of Saddam Hussein and named his roving sound system Desert Storm (he later took it to war-torn Bosnia on several “cultural aid” missions).

In these older despatches, Collin supplements his observations from the time with more recent visits to former protagonists, giving the original reportage an extra layer of poignancy. A decade after the Desert Storm maestro went on tour with the sound system, Collin, idly reading a newspaper article about troops being sent off to fight in Afghanistan, notices a familiar name and his jaw drops. “I wanted a new challenge,” explains Lance Corporal Keith Robinson.

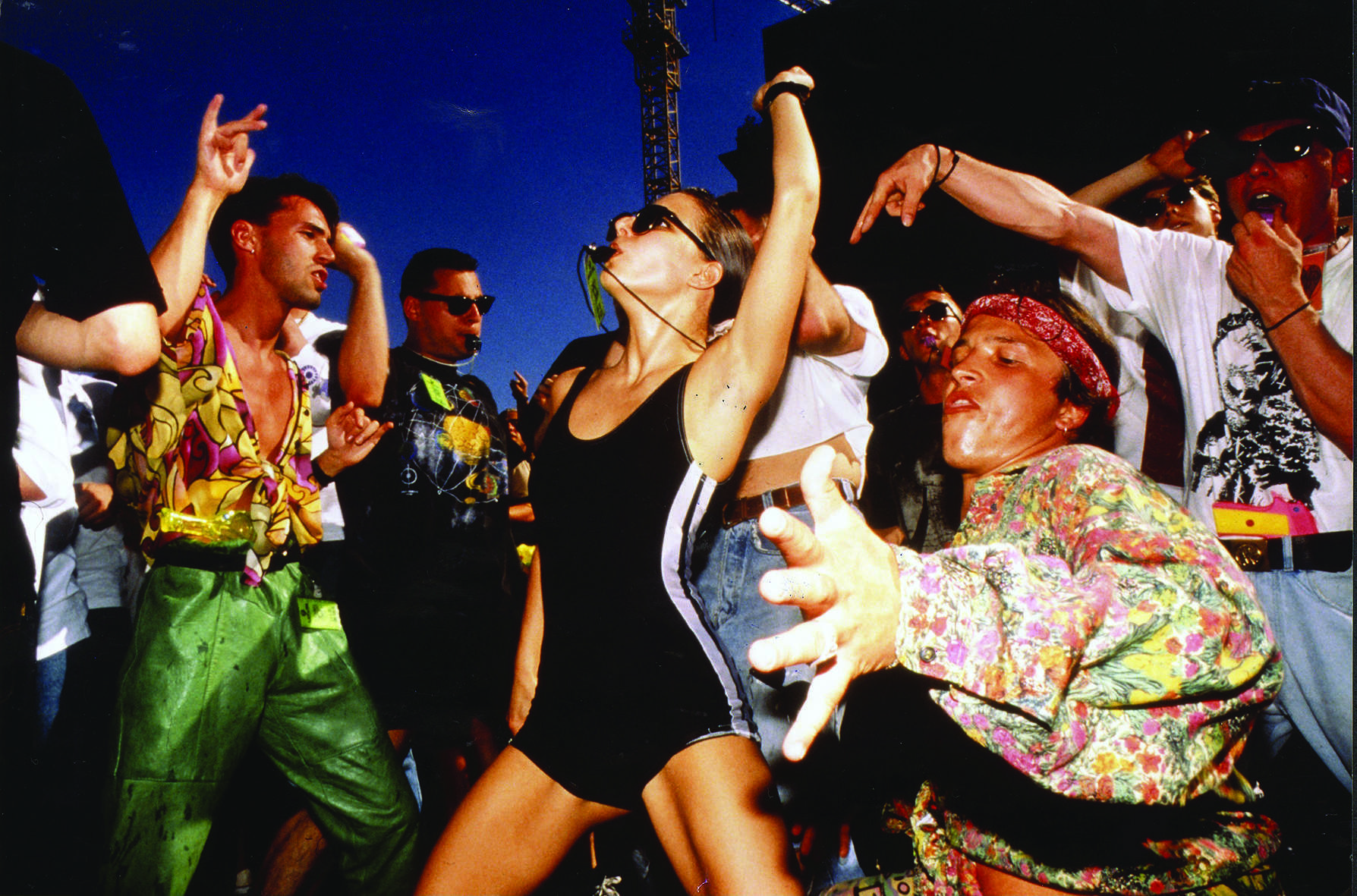

Most captivating of all is a long chapter on the story of the Berlin Love Parade, which ended in tragedy when 21 people were crushed to death in a stampede in a tunnel in 2010. Collin traces the city’s libertine history and the techno festival’s roots in “that glorious period of liminal grace” after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when the perfect coincidence of MDMA, acid house and grand historical change seemed to offer a more peaceful and just future for Europe.

The annual festival had grown so big by 1996 that it was marching 750,000 revellers from the Brandenburg Gate, a symbol of cold war division, down Straße des 17 Juni, the old Nazi parade route. It is a beautiful detail that, in 1989, the Love Parade’s first year, the organisers of what was ostensibly an unashamedly hedonistic carnival applied for a political demonstration permit for the festival – in doing so, freeing themselves from the burden of having to pay for policing or the post-festival clean-up. They got the permit and retained it until 2001, by which time money, tourism, cocaine, superstar DJ culture, corporate sponsors and ossifying music had led the utopian parade down the inevitable path of becoming a brand – “turning rebellion into money”, as the Clash once put it.

Registering the Love Parade as a political demonstration was not just a cheeky way of sidestepping costs that its idealistic dropouts could not afford. It speaks of a much grander point: music and youth culture have never needed explicitly to proclaim that “the times they are a-changin’” – they only have to show that they are. Protest songs are every bit as varied (in quality and form) as the love song, as Dorian Lynskey showed in 33 Revolutions Per Minute. But the more important lesson from Collin’s excellent book is that it is the world around the song, from the listeners and dancers to those dropping the needle or pressing Play on iTunes, that lends music its political power.

Among several interesting non-musical reference points, Collin draws on the anarchist philosopher Hakim Bey’s vision of a “temporary autonomous zone”, a popular idea on the pre-Criminal Justice Act rave scene: an unpoliced space, free from judgement and free from the authorities. It was the desire to find and create such a zone that propelled Keith Robinson and his band of narco-sonic explorers in Desert Storm.

It’s a good shorthand for many of these spaces carved out by people striving for freedom and documented by Collin – from elderly women of Istanbul crooning sad laments in Gezi Park to rave-era “psychonauts” with Mohicans and hi-vis jackets trying to start a sound system in the middle of the Czech countryside.

Pop Grenade: From Public Enemy to Pussy Riot, Despatches from Musical Frontlines by Matthew Collin is published by Zero Books (260pp, £12.99)

This article appears in the 23 Sep 2015 issue of the New Statesman, Revenge of the Left