If you want a sense of the Britain of 40 years ago, a good place to start is the feature-length film Rude Boy, released in 1980 and put together over the preceding two years. Co-starring the Clash and centred on an amiably daft fan of the band called Ray Gange, it mixes up fact and fiction, but delivers a portrayal of its time and place that grimly rings true.

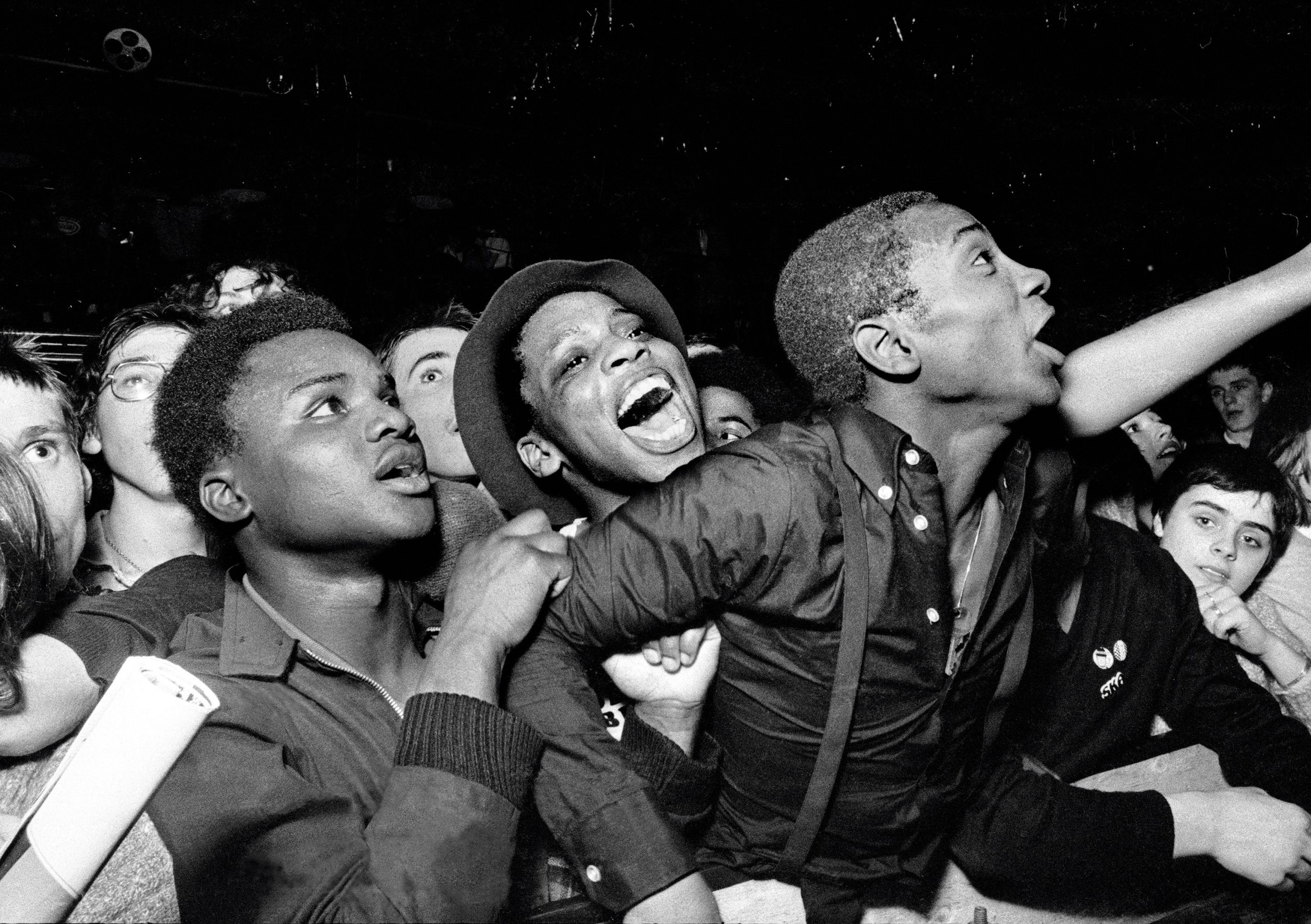

London is a shabby mess, all sticky café tables, musty-smelling pubs and Soho sex shops. The band’s concerts are regularly disrupted by violence. Through the cracks in a deeply troubled country’s psyche come the National Front (NF), marching through multi-racial parts of the capital with the protection of the police, who are both racist and corrupt. The Clash’s supercharged music sounds like a desperate attempt to hurtle out of all the horror towards something – anything – better, never more so than in a sequence filmed at a huge anti-fascist “carnival” at Victoria Park in Hackney, in which the opening seconds of their punk hymn “London’s Burning” turn a 100,000-strong crowd into a heaving, ecstatic mass. It’s on YouTube: there are few more thrilling portraits of rock music’s political oomph, and the era when it arguably reached its peak.

David Renton’s Never Again is a forensic retelling of the story of the two organisations that organised the Hackney event and the anti-fascist march through London that accompanied it, and the political ferment that gave rise to them. Rock Against Racism (RAR) was a brilliantly unorthodox meeting of pop culture and politics, founded by the music photographer Red Saunders in response to a drunken onstage outburst in August 1976 from Eric Clapton (“This is England, this is a white country, we don’t want any black wogs and coons living here,” he allegedly said, apparently untroubled by the fact that he owed his career to black music).

The Anti-Nazi League came a little later, thanks to an alliance between elements of the Labour Party and the far-left Socialist Workers Party, which was also involved in RAR. At the time, both were maligned as “front” organisations subject to the cynicism and deceptions of the SWP’s Trotskyism, but the truth is very different: thanks to an appeal that went way beyond the usual suspects, they embedded anti-fascism in the culture, and pushed the NF back to the margins. Retrospectively, the late SWP activist David Widgery captured what had been achieved: “For a while we managed to create, in our noisy, messy, unconventional way, an emotional alternative to nationalism and patriotism, a celebration of a different kind of pride and solidarity.”

Renton eloquently portrays the political battlefield on which all this happened, not just through high-profile events, but also his experience at primary school in late-1970s west London: “the inkwell beside which a pupil had carved a swastika… the day ‘Jew’ became a verb among my classmates: ‘Jew him, Jew you’.” His observations are particularly acute when he traces the links between the UK’s economic decline and some people’s aggressive longing for the days of empire, which fed into the rise of a newly emboldened far right. One of the founding elements of the National Front, he points out, was the League of Empire Loyalists, led by a rum assortment of earls, barons and former air commodores who pledged to restore Britain’s imperial glory. The key figures who would later lead the NF passed through its ranks, fusing the league’s aggressive nostalgia and plummy racism with their own bigotries (anti-Semitism is a part of this story that is too often overlooked). All of these elements chimed with mainstream politics and everyday culture: the long reverberations of Enoch Powell’s “rivers of blood” speech, brazen racism within the Conservative Party, and the nastiness and nostalgia that bled out via everything from racist stand-up comedians to the Second World War comic books that were part of thousands of 1970s childhoods.

At least a quarter of Renton’s text is devoted to a history of the National Front and its leadership, which amounts to pages of dense detail about extremely horrible people, best read in small doses. But the book comes to life when it zeroes in on their opponents, and two things in particular: the bravery that led thousands of activists to confront the NF – and the police – whenever they gathered; and the inspired thinking, as manifested in a wider and deeper cultural fight that took place on the terrain gifted to them by punk and reggae. His treatment of the music and musicians concerned is sometimes inept (The Sex Pistols were not “utterly mercenary”; Elvis Costello was never a punk), but the stories he tells of Rock Against Racism gigs are vivid and stirring.

Perhaps the best encapsulation of RAR’s power is the story of a July 1978 carnival in Manchester, headlined by the Buzzcocks and the Birmingham reggae band Steel Pulse, and attended by 35,000 people. “Some of the NF’s periphery went to the carnival,” recalls one of the organisers. “We could see them talking to people, dancing.” Another insider remembers the crowd being full of “kids from every school in Manchester. These kids would then go back into the school and say ‘Where were you?’ to the local Nazi.” This was a new, instantly effective kind of politics, saluted in the Daily Mirror by its esteemed columnist Keith Waterhouse: “It transcends all the old boundaries of accent, upbringing or postal district, laughs at the supposed difference between one shade of skin and another… If it is a Trot conspiracy, tough luck on the conventional political parties who play it all so safe and down the middle that they have the popular appeal of yesterday’s gravy.”

Some 50,000 people are reckoned to have been members of the NF at some point or other; for a time, its electoral performance suggested it was moving beyond the political fringe. But by 1981, it had been beaten. That said, 1970s English fascism embodied currents that have continued to swirl around, and that have arguably since made their way even further into the political mainstream. Superficially, the most obvious inheritors of that decade’s far-right politics are the kind of English thugs who now sporadically appear in the news dressed in yellow vests, and take their lead from that latter-day chancer Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, aka “Tommy Robinson”. But as I read Renton’s book, I thought about a much more insidious set of links between then and now, and the way that old prejudices and cruelties have become newly respectable.

There are obvious lines to be drawn between the Powellite cry of “Send ‘em back” and the Home Office’s current hostile environment doctrine, as shown in the ongoing Windrush scandal. And when Renton describes the League of Empire Loyalists as “a movement of the old rather than the young, and of men with social power”, he shifts the reader’s attention to the present with even more clarity. That description surely fits the politics of Brexit, and the alliance of angry fifty-somethings who now howl their rage on Question Time and Boris Johnson, Jacob Rees-Mogg and Nigel Farage – whose delusions and prejudices deserve a cultural response that has so far failed to materialise.

I do not know what a 21st-century version of the Victoria Park carnival would look like, whether any musicians will ever again channel their time as brilliantly as the Clash, or if contemporary popular music could give rise to anything resembling Rock Against Racism. But this book once again put an inescapable thought in my mind: isn’t it time someone at least tried?

John Harris writes for the Guardian

Never Again: Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League, 1976-1982

David Renton

Routledge, 192pp, £16.99

This article appears in the 13 Mar 2019 issue of the New Statesman, She’s lost control