Madness in Civilisation: a Cultural History of Insanity from the Bible to Freud, from the Madhouse to Modern Medicine

Andrew Scull

Thames & Hudson, 448pp, £28

Around the start of the 20th century, mentally ill people were being described as “tainted persons”, “lepers”, “moral refuse”, “ten times more vicious and noxious, and infinitely less capable of improvement than the savages of primitive barbarism”. For many prominent public figures, including Winston Churchill and Woodrow Wilson, the remedy was eugenics – “the effort to rein in the propensity of the poor and the defective to breed”.

Many American states had laws prohibiting those assessed as mentally unfit from marrying, and some made provision for these supposed defectives to be sterilised. The practice of involuntary sterilisation was challenged in the law courts, but when it reached the Supreme Court in 1927 it was endorsed by the celebrated American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes.

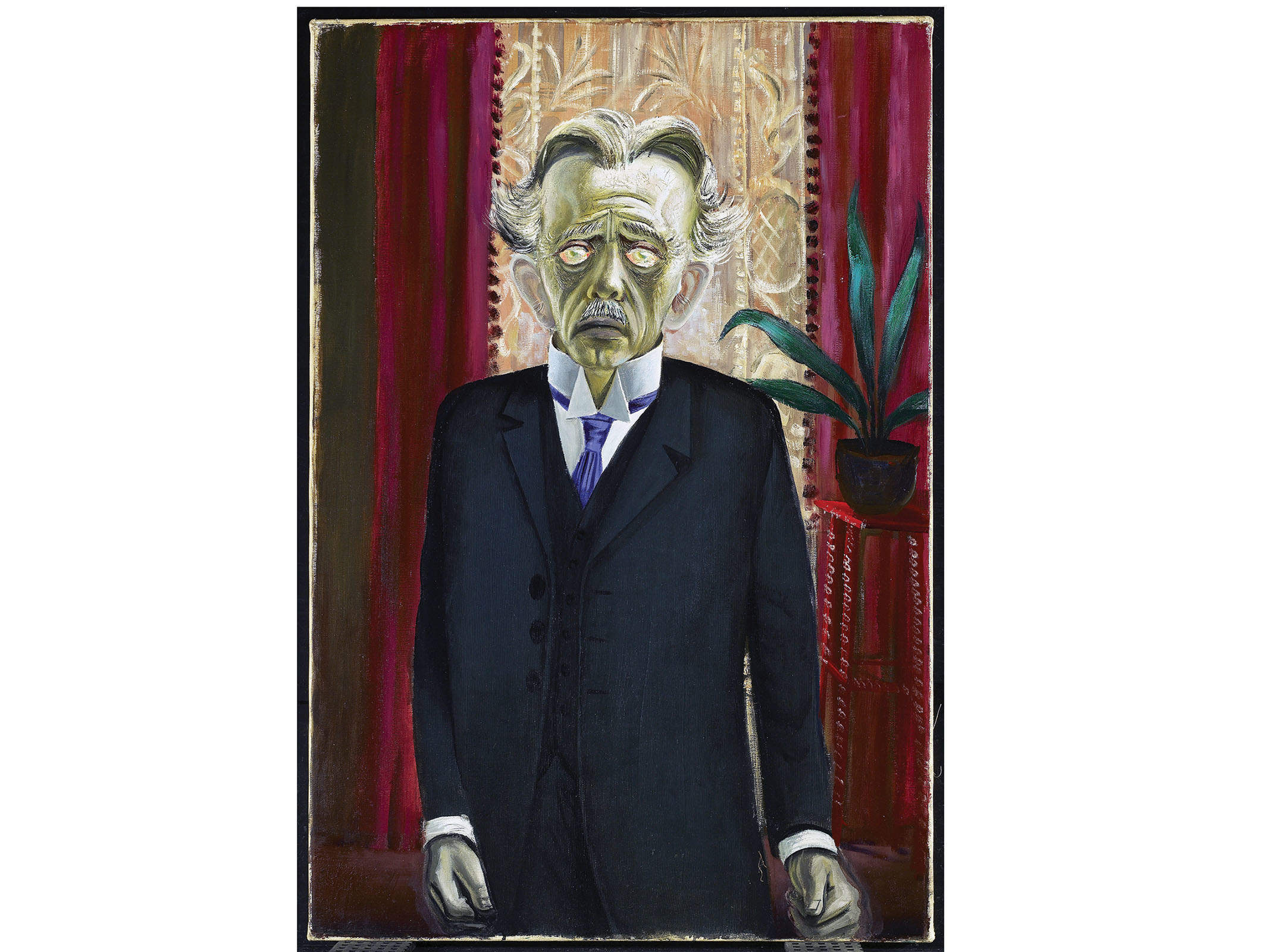

The American precedent was explicitly invoked when, in July 1933, within months of coming to power, Hitler passed the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring, which provided for the suppression of “life unworthy of living” (lebensunwerten Lebens). In October 1939 mentally ill people were rounded up and sent to mental hospitals where they were “disinfected”, in the first instance by lethal injection or shooting, then by gas when these methods proved too slow and cumbersome. By the end of the Second World War as many as a quarter of a million people had been murdered in this way. Throughout this period, German psychiatrists enthusiastically joined in implementing Nazi policies. In one of this book’s many striking photographs, the staff of a psychiatric hospital involved in the involuntary euthanasia programme are shown at a moment of leisure, being serenaded by an accordionist, looking “relaxed and happy after a hard day’s work”.

Describing these developments, Andrew Scull comments on how, from the 18th century onwards, many believed that madness was a condition which had emerged along with civilised life:

… it had become commonplace to see nervous illness of a milder sort as part of the price one paid for civilisation, indeed as afflictions to which the most refined and civilised were particularly prone. A century later, these ideas began to be extended to encompass the most severe and frightening forms of Bedlam madness. Insanity, alienists and their allies argued, was a disease of civilisation and the civilised.

At the same time as madness was being defined as a distinctively civilised malady, those who had been judged to be suffering from it were condemned as degenerates. Having cruel, pointless and damaging treatments inflicted on them in asylums, they were also the target of policies of eugenic extermination. If madness is a disorder of civilisation, societies claiming to be civilised have often resorted to barbaric and deranged practices in the attempt to cure it.

The foremost living scholar of the history of madness, Scull, a professor in the department of sociology at the University of California, San Diego, achieved some celebrity when, in a review of Michel Foucault’s History of Madness that appeared in the TLS in March 2007, he suggested that Foucault had postulated “a non-existent ‘Great Internment’” – a movement to remove the insane from society and place them in newly created institutions – in early-modern England. Scull’s sharp critique focused on what he regarded as deficiencies in Foucault’s historical research, but it also pointed to a weakness in the French postmodernist’s thinking, and in postmodernism generally. Denying anything like a constant human nature, postmodernists represent experiences that are found in widely varying societies and eras, and which in some cases may well be universal, as being historically discrete cultural constructions.

For Foucault, madness falls into this category: the human experience of insanity has been configured according to practices and discourses that reproduce structures of power. Scull does not deny this evident fact. This deeply humane book is full of examples of the many ways in which diagnoses of madness have been used as tools of inhumanity and oppression. Where Scull differs from Foucault is in recognising that derangement of the mind doesn’t date from some time in the 18th century, when some in Europe believed humankind was entering an era of reason. Whatever other follies the Enlightenment committed, it did not invent the experience of madness, which, as far as anyone can tell, appears to be generically human.

Vast in scope and learning, Madness in Civilisation explores the many different experiences and behaviours that madness encompasses and the diverse ways in which societies have coped with them. The result is a book that is as illuminating as it is compendious. By no means all cultures have regarded madness as an unqualified evil. Comic-book histories of ideas tell us that the ancient Greeks were devoted to rational inquiry as few other civilisations have been, but as Scull shows, certain Greek philosophers thought that losing one’s mind could open a window to knowledge. Plato believed madness was “another way of seeing”, secret, visionary and mystical, while Socrates pondered the meaning of dreams and listened to an inner daemon. The idea that madness could be a channel for truth resurfaced in medieval Christianity; in the Dutch Renaissance humanist Erasmus’s essay “Praise of Folly”, in Cervantes’s crazy knight-errant, Dostoevsky’s holy fools and the “super-sane” schizophrenics romantically imagined by the late-20th-century anti-psychiatrist R D Laing. (Scull doesn’t explore the point, but versions of this view of madness as a non-rational way of knowing also appeared in surrealism and other avant-garde artistic movements.) Madness has not always been regarded as a curse, even if that is how it has been experienced by many who have been labelled as mad.

Ranging through the ancient Hebrew and Hellenic worlds to imperial China, Islam and medieval Christendom, Scull goes on to consider theories of the humours in

early-modern times, citing Richard Burton’s shrewd advice to those who live in fear of melancholy: “Be not solitary; be not idle.” It was only in modern times, he argues, that those who had lost their wits were separated out from a much larger group of unfortunates – the crippled, the aged and the maimed – who were incapable of productive labour and therefore dependent on others. From the mid-17th century onwards great hospitals were founded in France, but those judged insane were always only a fraction of the inmates, who included pregnant women and wet nurses, people suffering from blindness and paralysis and other incurables of all kinds. Foucault’s notion of a “Great Confinement” oversimplifies these medical institutions, and also exaggerates their disciplinary role in the societies in which they emerged.

Alongside continuing popular belief in demonic possession and the practice of exorcism, old ideas of the humours renewed themselves in conceptions of madness as a type of nervous malfunction. One of the leading practitioners in this tradition was Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815), an entrepreneurial German physician who claimed to have discovered a vital force of “animal magnetism”, which he could control and use to effect cures for the manifold disorders of the rich and famous who flocked to him. As Mesmer came to understand it, sickness of the mind resulted when the flow of this force throughout the body was blocked. Denounced by jealous rivals and the subject of an investigation by a French royal commission, Mesmer was ruined and spent the last two decades of his life in obscurity. However, the idea that madness might be a physical disorder, which could be remedied by physical therapies, would be renewed in many different guises.

The development of psychoanalysis came about as an accidental by-product of this materialist approach to mental disorder. Through the work of the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-93) on hysteria, the idea that this and other psychological maladies were rooted in lesions or malfunctions in the brain and nervous system became an enduring part of the psychiatric dogma. Sigmund Freud had not initially intended to focus on hysteria, but in 1885, at a difficult moment in his career, he turned up in Paris and offered his services to Charcot. Nothing developed from their interaction and after five months Freud returned to Vienna to resume private practice. This failure to connect with Charcot may have led to Freud’s eventual abandonment of his project of a scientific psychology that would be grounded in neurology. The cause of hysteria, Freud later theorised, was not in brain lesions but in sexual trauma. Repressed memories of sexual abuse were the true roots of the strange behaviours and chronic difficulties that hysterics displayed. It was a bold claim, and was immediately ridiculed, the pope of Viennese sexology, Richard Krafft-Ebing, denouncing Freud as the author of “a scientific fairy tale”.

Freud went on to develop a theory in which fantasy and its repression were central to the life of the mind – a view that he continued to claim was scientific, though no longer based in neurology. His assertion of the scientific credentials of psychoanalysis spawned an enormous critical literature, much of it thoroughly tedious, with philosophers such as Karl Popper chipping in with accounts of scientific method that were designed to exclude Freud’s theories from the canon of respectable knowledge. Yet it was not the epistemological questions surrounding psychoanalysis that produced the greatest animosity to Freud’s ideas. As Scull notes – and he is not particularly sympathetic to psychoanalysis – the clear implication of Freud’s view of the mind was that mental disorder was not an affliction suffered by inferior specimens of humanity, such as the pitiful figures that languished in lunatic asylums, but a condition that affects us all to some degree. It was this suggestion that made Freud’s thinking so disturbing in his time, and it continues to disturb today.

Freud has been accused of having created a therapeutic culture in which inner conflict is viewed as a failure of psychological integration or adjustment – a condition that can be remedied by psychoanalysis. In fact, his view was the opposite: inner conflict goes with being human, and for that reason is incurable. If psychoanalysis had an overall aim, it was to learn how to live with inner conflict and self-division. But this was a daunting message, especially in the US, where Freud’s work was turned into a therapeutic technique promising self-realisation

and personal fulfilment. The original stoical impulse that informed his work has been lost and persists only in dissident currents of psychoanalytic thought, most notably the writings of Adam Phillips.

Freudian thinking had less influence on the way in which mental disorder is understood than is commonly supposed. The dominant approach continued to be one that looked for a technical fix. The American physician Henry Cotton (1876-1933) believed madness was an infection caused by infectious toxins, which spread through the bloodstream to poison the brain. To begin with, he thought that the tonsils were the chief agency of transmission, and implemented tonsillectomy on a large scale at the New Jersey state mental hospital he directed. When this failed to cure those diagnosed as deranged he moved on to the surgical excision of stomachs, spleens, cervixes and especially colons, where he believed the germs responsible for mental illness tended to accumulate.

A similar approach was followed in Britain by Thomas Chivers Graves (1883-1964), who removed teeth and tonsils and imposed prolonged colonic irrigation at the mental hospitals he directed in and around Birmingham. The work of Cotton and Graves received the endorsement of the British Medical Association and the Royal College of Surgeons. Elsewhere, physical therapies implemented as remedies for mental illness included the injection of horse serum into the spinal canal to produce meningitis and a fever that cleansed the nervous system of toxins, and lowering the body temperature to levels only just consistent with life (and sometimes, it turned out, lower than that). Lobotomy and electroconvulsive therapy were only the best known in an arsenal of weapons in what practitioners saw as an ongoing medical battle against madness.

In the late 20th century, drugs became the weapons of choice. Nineteenth-century psychiatrists had experimented on their patients using opium and marijuana, and in the 1920s barbiturates were used to induce periods of suspended animation. By the mid-20th century powerful antipsychotics were coming into play, and increasingly madness would be viewed through the lens of chemical reductionism. Meanwhile, policies of excluding mentally ill people from society were pursued in new ways. With asylums being shut down, many former inmates found themselves on the streets, and large numbers of these homeless, vulnerable people ended up in prison. In the US, Scull reports, the largest single concentration of the seriously mentally ill is in the Los Angeles County jail system.

“It is entirely possible,” Scull observes towards the end of this absorbing and often discomforting book, “that madness will after all turn out to have some of its roots in meanings, not Freudian meanings perhaps, but meanings nonetheless.” It is a tantalisingly oblique suggestion. One of the gaps in his magisterial survey is an exploration of collective madness – the propensity of large groups of human beings, even entire societies, to lose their mind. What does this recurring phenomenon tell us about the human pursuit of meaning and the fragility of what passes for sanity? Perhaps Scull will devote some of his future work to these large, unanswered questions.