The Essay: Finish the Bottle

BBC Radio 3

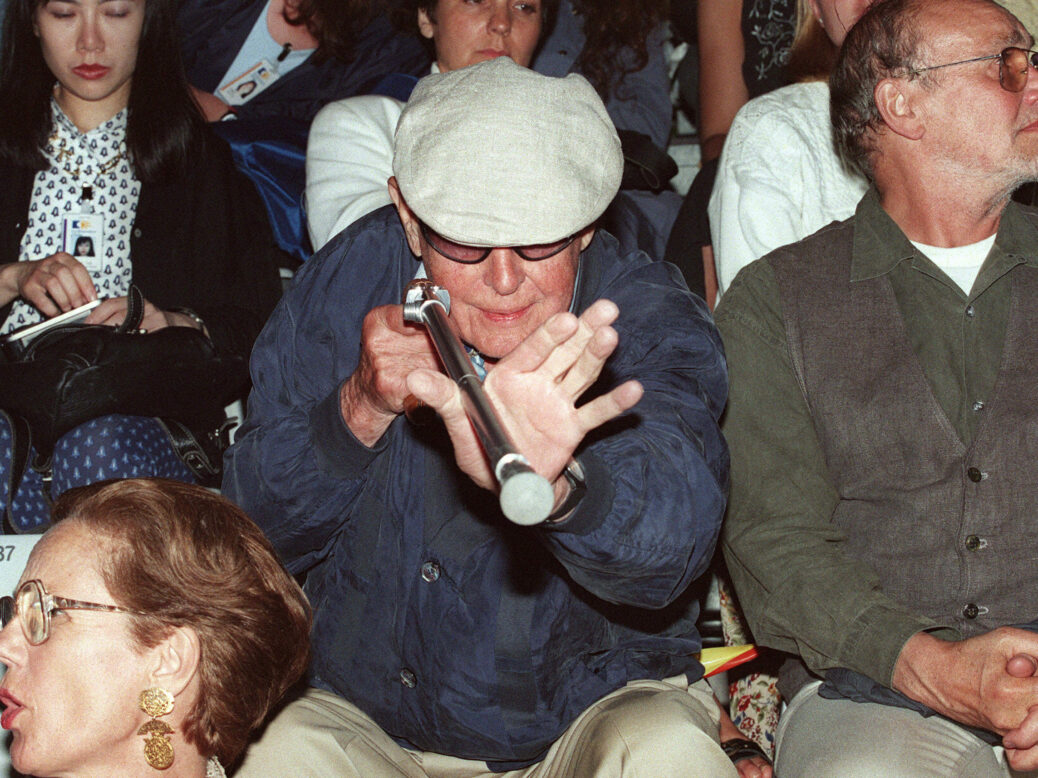

During a week of short monologues about being up close with well-known artists (24-28 March, 10.45pm), the critic Martin Gayford amusingly described a stressful encounter with the then 93-year-old Henri Cartier-Bresson. Taking out a tape recorder, Gayford was poised to press record when HCB boomed that he did not approve of having his words captured by a mechanical device (“To the best questions there is no answer!”). Since Gayford had been charged to conduct a major interview for a national newspaper, this development was a disaster. But he fished out a pen and notebook and managed, with his “scrawls”, to quote the photographer on exotic irrationalism, his nanny from Wolverhampton and the Russian Revolution.

“There is only one thing,” HCB told him. “The glance. It’s a joy. It’s an orgasm. You can teach everything except sensitivity and sensuality. Can you imagine a professor of sensitivity at the Sorbonne?” Your reviewer was impressed. Gayford’s note-taking skills must have been exemplary. I once conducted an interview with Oliver Stone, which – let’s put it down to nerves – I convinced myself that I could do in shorthand. As the director spoke in a low, meandering voice, I filled the pages of my notebook with enormous swirls, as though these were an obscure but ingenious form of notation. At the time, the loops made sense – but when I came to write it all up, it was like trying to decipher cave markings.

Martin Gayford is possibly the one person on earth who would have been able to make something of them. His skill with reconstructed speech is deeply mysterious. In his memoir about sitting for Lucian Freud, Man with a Blue Scarf, Gayford quotes the painter chapter and verse and yet couldn’t possibly have been sitting there for seven months with a pen and paper (Freud objected to a mere move of the leg), or surreptitiously changing batteries on a hidden tape recorder. Yet Freud’s easel-talk in that book reads just right, never more so than when he slams Rossetti as “the nearest painting gets to bad breath”. How does Gayford do it? Is he the ultimate mimic? Does he have a kind of photographic memory? Either way, it’s a skill as unique as most things his subjects have to say.