The Chancellor’s Comprehensive Spending Review surprised no one. Further cuts across the board, pay freezes for the public sector, more hoops for benefit claimants to jump through… and protection for elite sports and defence- Plan A all the way.

The Coalition’s continued austerity drive maintains its stranglehold on British growth, while their agenda of Hayekian reforms are less like rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic, and more like trying to cut wage costs by firing crew members as the waters rush in.

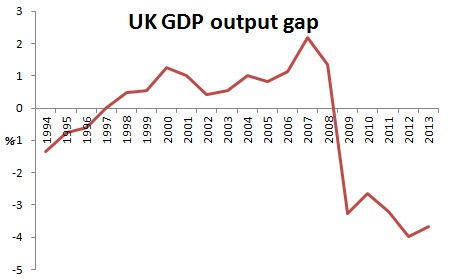

So how is plan A working out?

Fig 1: Source Econstats/IMF, 2013

Fig 2: Source: ONS: UK Public Sector Finances, Jun 2013 & OBR Economic & Fiscal Outlook, Mar 2013, Table 4.36 (pink=forecast)

Figure 1 shows how far the economy is operating below “potential growth”- the pace we would be growing at in normal times (neither boom nor bust). In the last 5 years, we have lost a compound GDP growth of almost 18 per cent. In current prices that equates to a shortfall of around £300bn – or almost three times the size of the current deficit, which incidentally – as can be seen in Figure 2 – is no longer falling.

And this is all against a backdrop of a labour market in tatters- chronically high joblessness (despite disingenuous statistics about private sector jobs), 20 per cent youth unemployment and what looks like a marked shift from cyclical to structural unemployment (temporary to long-term), as shown in the ONS’s latest report:

.jpg)

Fig 3: Source: ONS, Economic Review, June 2013

The figures above tell a story. The country’s resources- particularly labour- are unemployed, so our potential output is not realised, whilst individuals’ reduced spending power means less demand and less consumption – so the national income is lower. This causes an automatic reduction in tax receipts and an increase in social transfers which increase the deficit. And as growth stalls, the debt-to-GDP ratio is increased (via a smaller denominator), so the national debt looms ever larger.

Possibly the most shocking evidence of how bad things are can be shown by comparing our recent recovery to the recovery from the Great Depression of the 1930s:

Fig 4: Source: Eurostat, Maddison Project, 2013.

By this measure, the Great Depression doesn’t look so great, and we are deep in the worst economic crisis of the past century.

But since the very public bank bailouts and stimulus packages that followed the financial crash, policy makers the world over seem to have accepted that we are in a “new normal”. A crude reflection of this can be seen in the number of times the terms ‘crisis’, ‘recession’ and ‘new normal’ have been Google searched over the past few years.

Fig 5: Source: Google trends, accessed 2 July 2013

Why have crisis economics been abandoned in the middle of a crisis?

Instead, the economic discourse has defaulted back to the usual arguments between two dichotomised camps- call them what you want: Left-wing vs Right-wing, Socialists vs Free-marketeers, Aust(e)rians vs Keynesians, Nasty Party vs Scroungers, etc.

Some of the passengers on the Titanic might have thought that the ship would be faster and more efficient if it was not weighed down by the many third-class passengers, whose lowly ticket prices did not contribute as much to the vessel’s opulence. Equally, some may have felt that ticket prices should be lower, or that all passengers should have access to the ship’s offerings. But when she struck the iceberg, these quarrels were forgotten.

The longstanding question around the role of the state to intervene, distribute and employ is a fundamental one, but a state of crisis is not the time for fundamentalism.

Unfortunately, many on the right think that this is precisely the time for it. By dressing their long-held beliefs up as crisis-management tools, they can hold the country hostage “for the greater good”- the Tea Party’s obstinacy over taxation is one very public example of this, but it is just the tip of the iceberg…

The problem is, no right-wing economist has ever published a credible plan to recover from the kind of demand-driven shock we are facing, and recent attempts to contort their usual arguments for economic management into a path to recovery have been disastrous. Papers by Alesina & Ardagna, and Reinhart & Rogoff briefly showed that austerity could be expansionary and that government debt would hamper growth- before being thoroughly and publicly debunked.

But still we hear about the danger of inflation, the importance of encouraging job-creators by lowering top-rate taxes and the need to let austerity “do its work”, by shearing off the weak parts of the economy. These are not crisis management tools, they are the same arguments made by right-wing economists at all times!

But of course there is a custom-designed tool for our current situation.

Whilst their recoveries at year 5 may look different because of international policy choices, it remains the case that no economic crisis in history so perfectly mirrors our own as the Great Depression.

And written in response almost 80 years ago, Keynes’ General Theory clearly sets out the path for recovery in a world of low demand, private deleveraging and ineffective monetary policy: public borrowing to finance stimulus- if the private sector won’t create growth then the public sector must.

Fiscal policy is one of the most fundamental tools of government, and its use to rebalance the economy should not be thrown by the wayside because some people confuse it with a clandestine objective to impose socialism on the state.

With all this in mind, it was staggering to hear it announced that a Miliband Labour government would not borrow more to reverse Coalition spending cuts in 2015-16- in order to remain “credible”.

If the country has regained normal levels of growth by that stage, consolidation may be appropriate- but why explicitly rule out the use of one of the basic tools of government two years down the line?

If One Nation Labour aims to emulate its predecessors by courting Tory voters, abandoning the obvious case for fiscal stimulus is a new and irresponsible way of doing so.

Their change of course marks the retreat of the last bastions of Keynesianism from British politics: now we really are all in it together.

Meanwhile, the ship is still sinking…