Over the Christmas period, the Prime Minister will consider the role of the House of Lords in scrutinising legislation. Bruised by recent defeats in the upper chamber, it would be tempting to give the Lords a bloody nose. In the interest of the country, he should resist.

The question facing the Prime Minister dates back to October, when the Lords voted to delay a statutory instrument – a secondary piece of legislation – that contained the government’s controversial tax credit reforms. This sparked a small but potentially significant spat. The government argued the vote broke the convention that the upper house does not block money bills or manifesto commitments. The Lords said their actions met neither of these tests. As a result, the government set up a review, chaired by Lord Strathclyde, into the powers the House of Lords should have over Statutory Instruments.

On “trash day” – the final sitting of Parliament before Christmas – the government published the report. Lord Strathclyde suggested the primacy of the House of Commons needed to be restated, and recommended the removal of the Lords’ ability to block secondary legislation. Under the proposals, the House of Lords will now only be able to ask the Commons to think again.

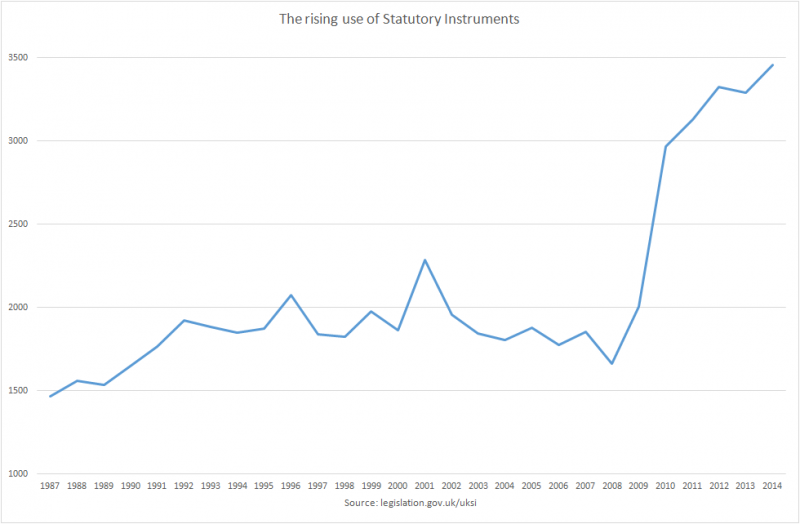

Lord Strathclyde’s recommendation is ill-judged. Statutory Instruments are now a major legislative tool for the executive. Their use has more than doubled since the 1980s, and Hansard Society estimated Statutory Instruments currently account for as much as 80 per cent of the legislation that impacts citizens.

Despite this, they are given less parliamentary time than Bills, enabling governments to push through their legislative programme with little scrutiny. By removing the Lords’ veto, opposition to the executive would be further weakened. Given the partisan nature of the House of Commons, a determined government could pass any piece of secondary legislation it wished.

Eroding Parliament’s already inadequate scrutinising function increases the risk of poor legislation. The government should tackle, rather than exacerbate, this lack of democratic accountability. Beefing up the oversight function of the House of Commons would be a good place to start. The existing committee system for revising legislation gives a partisan group of MPs, who often have no experience in the area, the duty to hold the government to account: those being scrutinised are effectively managing the scrutiny. As Reform has argued in A Parliament of lawmakers, handing the more expert and independent select committees this function would be a step in the right direction.

Checks and balances do not tend to exercise the British electorate. However, dry constitutional questions – such as the one addressed by Lord Strathclyde – are crucial to ensuring a Parliament can hold the executive to account. Resisting the immediate political benefits of accepting Lord Strathclyde’s proposals will be difficult for a Prime Minister with a slim majority in the House of Commons, and no majority in the House of Lords. Nevertheless, he must do so in the national interest.