Under the gaze of Big Ben, a man with blue eyes and a neat white moustache is rolling a cigarette outside the main entrance to Westminster Underground station. In his black beanie, woolly jumper, anorak, jeans and walking boots, the 60-year-old doesn’t look so different from the tourists swarming past, dressed for a daytrip in windy springtime London.

Yet his enormous rucksack, which he kindly offers me as a seat, tells a different story. After leaving his ex-partner, and with nowhere else to go, Peter – who grew up near Birmingham – travelled to London and has been sleeping rough in the Tube station for eight months.

Four weeks ago, he was instructed to move. Three police officers came up to him, he recalls, and told him to leave under Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act, a law written in 1824 still used to criminalise sleeping rough or begging today.

To demonstrate how archaic this law is, one of the offences under Section 4 reads:

“…wandering abroad and lodging in any barn or outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in the open air, or under a tent, or in any cart or wagon, and not giving a good account of himself or herself.”

Although Scotland repealed this Dickensian legislation nearly four decades ago, it is very much alive in England and Wales – with 2,947 prosecutions in 2015-16 – and right on the doorstep of the Houses of Parliament, too.

When I visit the station on a Wednesday afternoon in May, I count five people sleeping in the main station and its tunnel walkways. One tunnel leads to an underground entrance to parliament, which MPs, peers and their staff use every day.

There is no one sleeping directly outside that door today, but there are tell-tale signs that somebody has been – a flowery bedsheet, flattened cardboard, and remnants of take-away food and cigarette ends.

“I was sitting in the tunnel reading a newspaper,” Peter tells me. “The police came up and asked me to move and get out of the tunnel. They’re picking on the harmless, a lot of people have no means of support.”

Peter is not the only one. There have been reports like this from many homeless people who sleep in the tunnels.

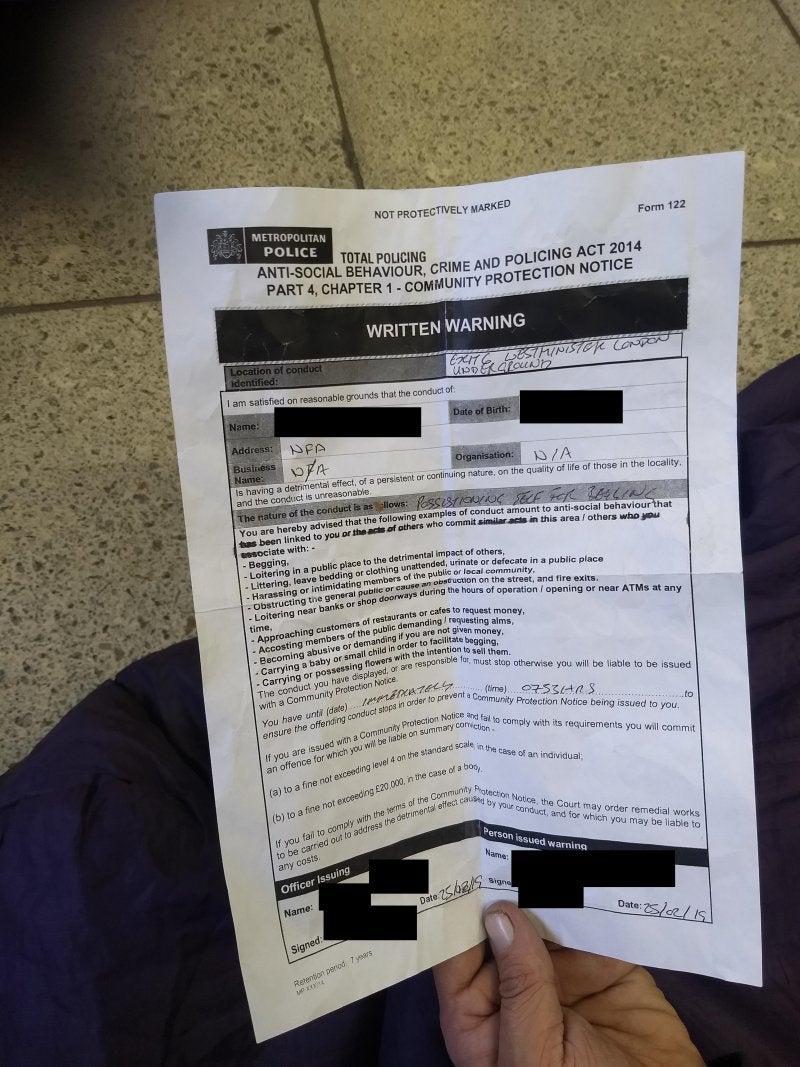

Earlier this year, some were handed Community Protection Notices (CPNs) – or woke up to find one – threatening fines of up to £20,000 for antisocial behaviour, for reasons such as “positioning self for begging” and “loitering to the detriment of others”.

All photos and consent to share: Labour Homelessness Campaign

One rough sleeper was stopped and searched by police:

The code letter ‘N’ means the reason for the search came under “terrorism”.

“This has happened before,” says Paul, a 51-year-old Big Issue seller who was born in Portugal and has lived in London for 19 years. He has been sleeping in the station for five months, having struggled with gambling, losing his restaurant business and his relationship breaking down.

“One of our colleagues in Victoria got woken up and given a map of the area where you’re not supposed to sleep by police. It’s just a matter of time before everybody is moved.”

Peter says there are places that he and his peers are “not allowed to sleep, eat, fart or anything”. He jokes that soon they’ll be moved out to fields in the countryside, “where we’ll need to look out for tractors!” He feels “belittled”, and argues that if people like him aren’t allowed some semblance of a normal life while they sleep on the streets, “we might as well just throw ourselves in the Thames”.

The Metropolitan Police confirms that sanctions can include arrests, cautions, warnings, penalty notices or community protection notices.

Its officers are “required to uphold the law and to enforce lawful measures to address issues such as anti-social behaviour and to encourage those sleeping rough to seek support and safer accommodation”, says a spokesperson, and “it would be wrong of us to refuse to play our part in a partnership effort to prevent people sleeping rough on London’s streets. Where enforcement is required, the Met does have a duty to act.”

In Westminster, “the police, Westminster Council, and outreach partners work together to engage with people on the street, identify their support needs, and try to connect them with services, including temporary accommodation, mental health or drug and alcohol support,” they add.

According to the British Transport Police, “responding to homelessness on the Underground is a challenging issue”, and its role “first and foremost” is to “identify those individuals with vulnerability concerns and ensure they are appropriately safeguarded”.

It adds: “In Westminster we are working closely with our colleagues at the Metropolitan Police, Westminster Council and outreach partners to engage with those sleeping rough around the station and identify the appropriate support for them.

“However, police are still required to uphold the law and occasionally, officers will move on homeless people if they are obstructing stations or exhibiting anti-social behaviour. When this is the case, safeguarding that person and providing access to the available support will still always be the primary concern.”

While Westminster’s rough sleepers “get good and bad” police officers, according to Peter, he believes that when “someone from on-high says ‘get rid of them’, they start throwing their orders about”.

For example, he says an MP complained to the Metropolitan Police about rough sleepers in the station. This is confirmed by Neil Coyle, a Labour MP who chairs the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Ending Homelessness.

“The frustration I have is that it was an MP who complained about homeless people sleeping in Westminster station outside the entrance and exit,” Coyle tells me. He has sent a Freedom of Information request to the Met, which he hopes will name the MP in question. “They are able to share some information but they haven’t yet,” he adds.

“These are people trying to sweep the problem not just under the carpet but into the drain,” he says. “They are trying to hide a problem. Rather than actually get on with dealing with tackling the causes of homelessness, they just don’t want to see it.”

****

Last December, a 43-year-old man sleeping rough called Gyula Remes collapsed by the station’s parliament entrance, and died later that night. His death followed that of a 35-year-old man in February of the same year, in the underpass of exit three in the same station.

According to the Bureau for Investigative Journalism’s Dying Homeless project, 796 people in the UK have died on the streets or in temporary accommodation since October 2017. That’s an average of 11 people a week. Last December, homelessness deaths were calculated to have risen by 24 per cent over five years, according to the Office for National Statistics.

MPs left flowers and cards. Remes’ death was called a “wake-up call” for Westminster. Yet since then, the associates Remes left behind in Westminster Tube have simply been asked to move on.

“The MPs get up off their lovely cushioned seats after getting drunk or whatever they do, and they come and say ‘we’re really sorry, we’re going to do this and that’, but a lot of them just ignore us,” says Peter.

“They need to sit up and listen, we need to make them pay attention,” he adds. “Was his [Remes’] death in vain? Why have they [MPs] allowed this to happen? If he’d been given shelter, he wouldn’t have been on the streets. He could’ve been off the streets far quicker if they did something. All these people that are dying, no one cares about them.”

Paul agrees, saying it’s “not an issue” for politicians walking past them who “turn a blind eye”, and also notes that the services weren’t there to help him with his gambling problem, having “tried everything” he could to seek help.

The main support he receives now is from ordinary passers-by, “not from the government”. “The government have never helped with anything,” he says.

“The Tories are the worst culprits,” Peter argues. “If they can’t see us, they don’t want to know about us. It’s out of sight, out of mind. They’re too posh and so far up their own backsides, they don’t want to help. If they listened to homeless people, they’d get a better picture of what to do.”

****

As of the latest rough sleeping figures in England, the place with the largest number of rough sleepers is Westminster. In autumn 2018, 306 people spent the night on the streets of the borough that is home to Westminster and Whitehall, up by 41 per cent on the previous year, and more than double the following borough on the list, which is Camden in north London.

However, when they were announced, these figures were a “step in the right direction”, according to the Housing, Communities and Local Government Secretary James Brokenshire. This was because rough sleeping had decreased by 2 per cent in a year. But the count still showed an 165 per cent increase in rough sleeping since 2010, and London alone saw a 13 per cent increase.

A Westminster City Council Spokesperson said: “We spend £6.5m a year on housing, mental health support, drug and alcohol addiction support for people sleeping rough on our streets. We can help most people who engage with us – 97 per cent of new people sleeping rough that engage with us are helped off the streets for good.

“We are aware that the underpass can be a rough sleeping, anti-social behaviour and begging hotspot, and our outreach teams regularly visit and try to connect people there with our services.”

The government announced a Rough Sleeping Strategy last August, aiming to halve rough sleeping by 2022 and end it in 2027. But half of the £100m committed to this strategy was already going towards rough sleeping initiatives, and the rest wasn’t “new” money either, simply reprioritised funds from the existing Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government budget.

“They re-announced money that was already a given,” says Coyle. “The commitment just isn’t there.”

****

Activists aiming to repeal the Vagrancy Act are trying to help Westminster’s rough sleepers. The Labour Homelessness Campaign, launched last December but separate from the official party, staged a protest in the station last Tuesday. Along with other homelessness groups, they broke the Vagrancy Act along with the rough sleepers by standing and sitting in the public space with them.

Shaista Aziz

“One of the things that’s really come through from the campaign is the way that people experiencing rough sleeping are being criminalised,” says Shaista Aziz, an Oxford City councillor who co-founded the campaign and attended the protest.

“And in many, many cases it’s being done by Labour-run councils and that’s a fact. So we have to understand that fact, those of us who are Labour councillors. We have to push back against the way the system is set up.”

An example of this is Manchester council looking into £100 spot fines for rough sleeping. The latest figures show 36 per cent of local authorities have used Public Spaces Protection Orders (PSPOs) specifically against rough sleepers despite the guidance telling them not to.

“They’re disproportionately impacting people who are existing on the streets,” says Aziz.

She also believes austerity has led to the neglect of people’s needs, with “services not functioning fully” condemning them to the streets. “Austerity has really decimated all public services but particularly those for the most vulnerable, if you look at rehab, drug facilities, domestic violence services…”

Well-resourced addiction services, for example, would help people from reaching crisis point. Someone like Paul, who is now selling the Big Issue and has no roof over his head, would have benefited. Instead, he says he carries a “bag of regrets” around with him about his gambling.

“The solution isn’t to throw the homeless people into the river, it’s to get on with the more difficult solutions,” says Coyle. “Around housing itself, obviously, support charities and councils to do more, drug and alcohol treatments, which are being slashed to bits. And of course, support for people with mental health conditions.”

As an MP, he feels “ashamed” to walk past homeless people on his way to work. “Westminster is one of the tourist hotspots for London, so as a symbol of who we are and what we are as a country, we have a World Heritage Site, Westminster itself, surrounded by people who have been badly let down by government policy,” he says.

“Millions of tourists who come through Westminster every year – to see this in the sixth wealthiest nation on the planet is an embarrassment and an international humiliation.”

Back underground, a service information board bears a marker-penned message written in capital letters by Tube staff: “Do something today that your future self will thank you for.” A call that many of this station’s users seem to ignore.