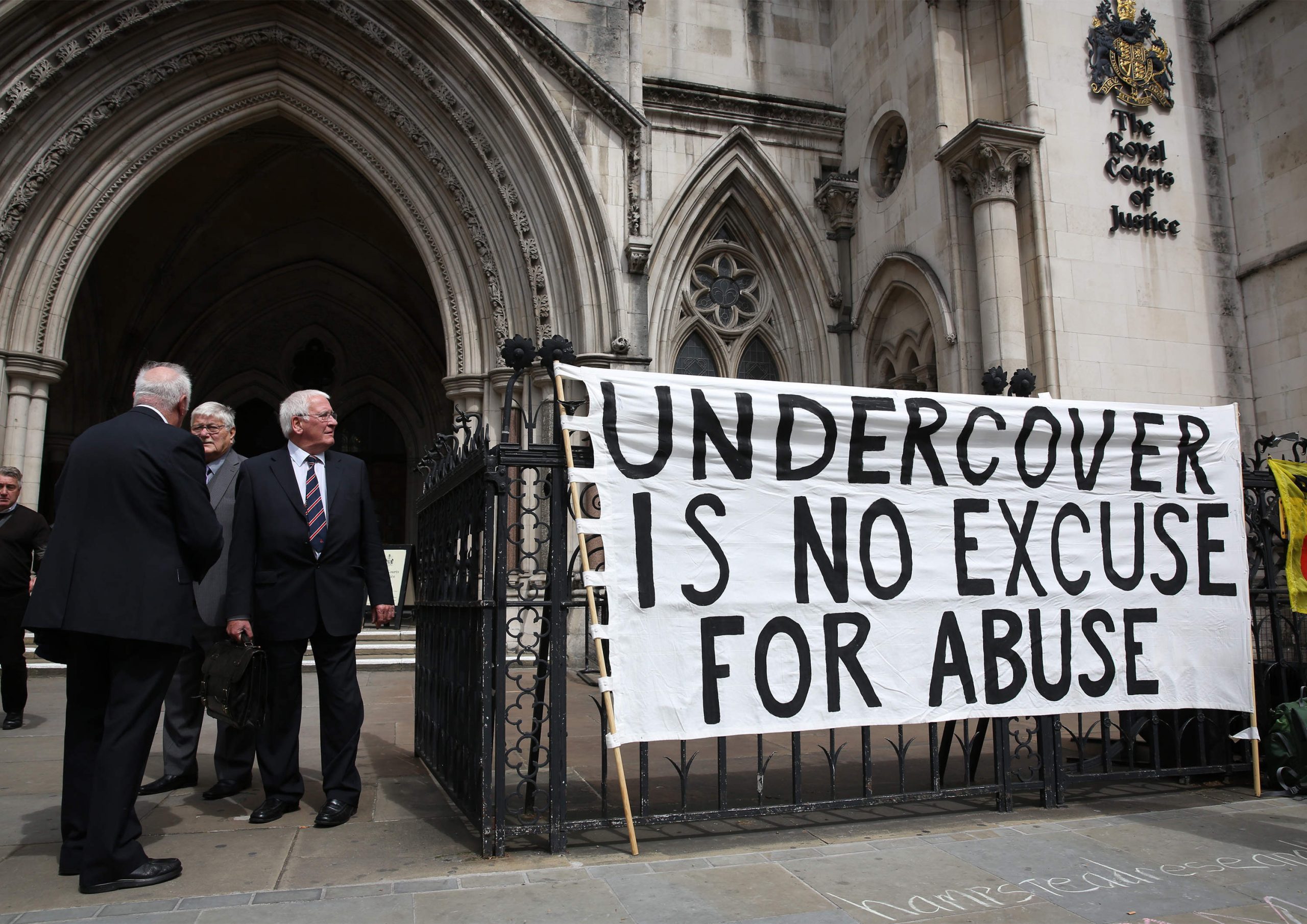

Of all the scandals to have undermined trust in government and the police in recent years, one of the most shocking was “spycops” – the story of how secret police spied on, and in some cases had sexual relationships with, political activists.

Since Mark Kennedy was exposed as an undercover officer in 2010, around a dozen others have been identified thanks to the meticulous research of campaigners and journalists. The stories that emerged confirmed what many – especially environmental or direct action campaigners – had long suspected: that undercover officers were routinely infiltrating political movements.

But some facts shocked even the most cynical. Officers adopted the names of dead children when creating their back stories. They slept with targets, in one case fathering a child with a “partner” – all while leading parallel, secret lives. Officers spied on left-wing politicians like Jeremy Corbyn and the Green Party peer Jenny Jones – and may have shredded files to cover it up.

The revelation in 2014 that officers spied on the family of murdered teenager Stephen Lawrence was the final straw, and a judge-led public inquiry was ordered by then-home secretary Theresa May.

Three years later, this inquiry is now mired in controversy and spiralling costs. Police forces have demanded anonymity for officers, and many activists hold little hope for the “truth and justice” they were promised.

But despite considerable evidence of undercover operations taking place in Scotland over the years, the inquiry will stop at the border. Northern Ireland, too, is excluded.

But all this could change if Matilda “Tilly” Gifford wins her legal challenge this summer. She is seeking a judicial review of the Home Office’s decision to exclude Scotland – and additionally, of the Scottish government’s refusal to set up a separate inquiry.

Forced to crowdfund for the costs of the initial stage after legal aid was denied, Tilly, 32, is keenly aware of the significance her case could have.

“There’s just so much resting on this. It’s such an important issue of accountability and transparency.

“Now that we know all the intrusion and surveillance went on, all these state-sanctioned abuses… we can’t just backtrack and accept that we’ll never find out.”

It’s “comforting”, she says, to know that a parallel challenge is having some success in Northern Ireland. Jason Kirkpatrick, who says he was spied on by Mark Kennedy in 2005, won the right to a judicial review in February, and a full hearing will take place later this year.

Despite Labour MSP Neil Findlay repeatedly raising the need for a Scottish inquiry, the government north of the border seems to have been slow to respond. A review was ordered by Justice Secretary Michael Matheson, but it will cover only the last 17 years (the England and Wales Pitchford Inquiry, in contrast, will stretch back to 1968, when the infamous Special Demonstration Squad was formed). The fact that Matheson’s review will be carried out by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary Scotland (HMICS) led campaigners to dismiss it as a “whitewash”, accusing the government of “letting police mark their own homework”.

“There’s been enough HMIC reports in England to know they’re a waste of time and resources,” Tilly says. “We need to know the extent of it – how people were targeted, and why, and who commissioned it.”

Tilly, who now works as a gardener and runs a workers’ co-operative, says she was targeted by officers in 2009, offering her money to inform on fellow environmental activists. She taped the men boasting of their “hundreds” of informants, and provided the Guardian with the recordings. Tilly could find no proof the officers were really from the local Strathclyde police, as they claimed.

“Lots of people knew or assumed [spying] was happening but it was very hard to find proof,” she remembers. “But before the Mark Kennedy story broke, people just didn’t know the degrees to which police would go.

“When it was discovered that they had been systematically destroying the lives of women over the years, then suddenly the general public could understand how activists were being targeted. That was a pivotal change.”

She draws a comparison with victims of blacklisting: in 2009 it was discovered that construction companies had been keeping tabs on trade unionists and activists for decades, barring people from work and effectively ruining their lives. Indeed, there is evidence that undercover officers colluded with the operators of the blacklist, and political figures as well as trade unionists were found on the lists.

“They knew it was going on, their whole lives were affected – but they didn’t have proof,” she says. “Imagine, for the state apparatus to undermine you and interfere with your life. . .but you can’t say it out loud because you’ll be labelled a conspiracy theorist!”

Blacklisted workers have left messages of support on her crowdfunding page. Tilly says that has been “so encouraging – because it’s quite a lonely position. It’s terrifying to put your face out there and ask for money.”

For Scottish alleged victims of undercover police abuse to miss out on an inquiry and be left in the dark would be “tragic”, she adds. The discovery of Mark Kennedy’s role as an undercover officer has already led to the quashing of convictions, when it transpired he had withheld evidence vital to activists’ defence in court.

When (or if) more evidence of undercover activities comes out of Pitchford, it could expose “potentially the biggest miscarriage of justice in legal history”, Tilly thinks. “To have to sit and watch that happening across the border, when exactly the same practices were happening in Scotland . . . it would be painful, and ridiculous.”

The pressure is huge, she admits, but she is staying positive. “We all know it’s going to be a slow burner. It will take time. But it will have to come to light.”