In September 2006, as Tony Blair reeled from the “cash for honours” affair, his opponent vowed to set a different standard. “The public wants cleaner politics and better value for money,” said David Cameron. “Tony Blair’s government has tarnished politics and eroded public confidence in our traditional institutions.

“We need to restore trust and tackle the public’s underlying cynicism – that politicians put party before country and partisan spin before the truth. In short, society has changed. Politicians must change too.”

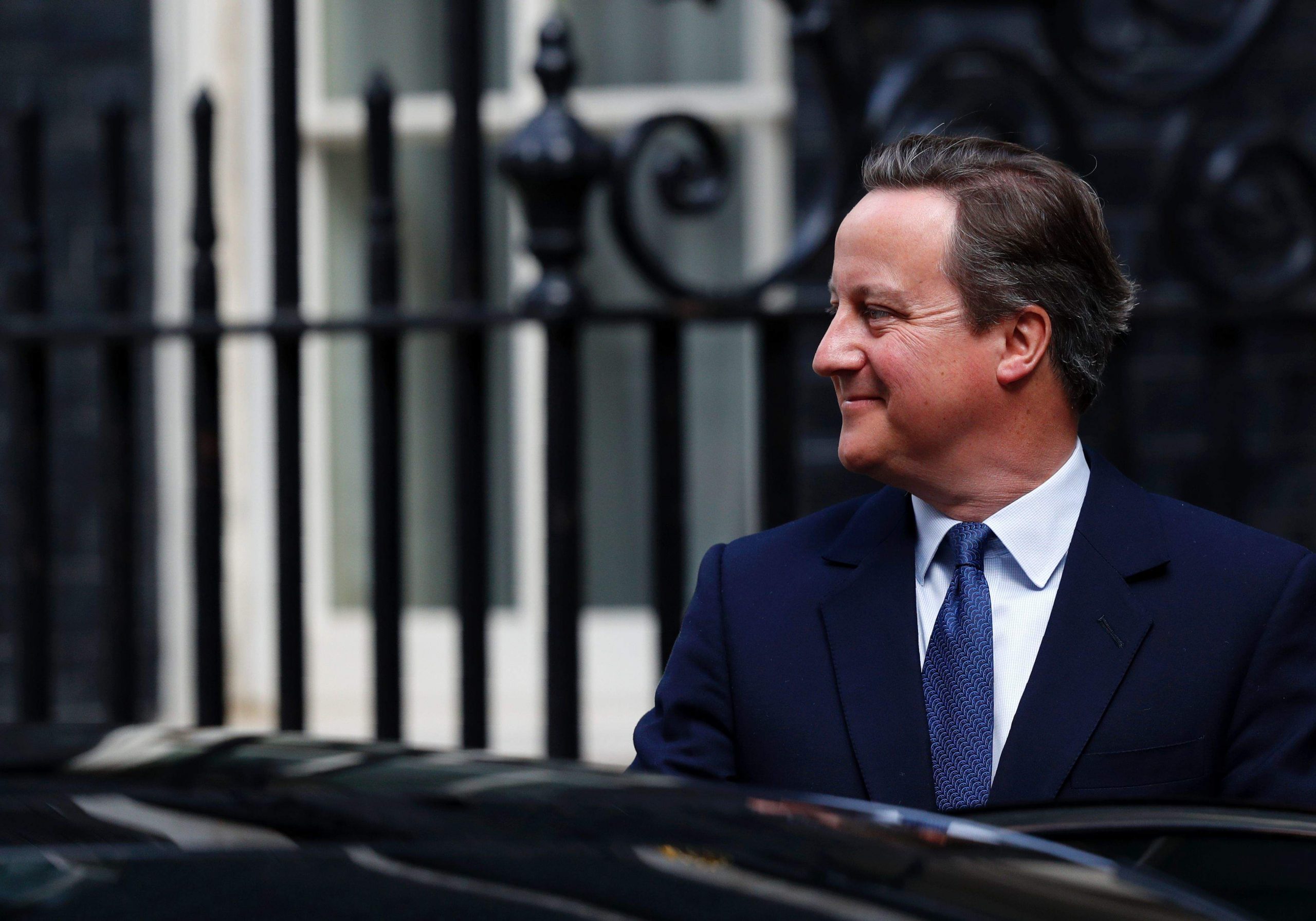

Nearly a decade later, Cameron’s resignation honours list aptly demonstrated how little has changed. When the details first emerged in the Sunday Times, many reacted with incredulity. Had the former prime minister really proposed to knight two Tory donors (giving £2.9m between them) and four serving cabinet ministers? (Their shared distinction being support for Remain.) To dole out honours to failed pro-EU campaigners? To reward a raft of friends and hangers-on? If one were to draw up a list to entrench public cynicism about politics it would be hard to improve.

But the surprise is that anybody should be surprised. Cameron’s valedictory awards are emblematic of his conduct in office: indifferent to reform and willing to exploit the constitution for partisan advantage.

It was the promise of “a new politics” that defined the coalition government’s opening moments in 2010. After the outrage engendered by the expenses scandal, Cameron vowed to overhaul a “broken” system. The Coalition Agreement pledged to reform party funding to “remove big money from politics”, to introduce a new power of recall, allowing voters to trigger by-elections against malfeasant MPs, to create a “wholly or mainly elected upper chamber” and to fund 200 open primaries in seats which had not changed hands for decades. Not one of these promises was kept.

Cameron, who was deservedly pilloried over “dinners for donors” in 2012, never made any serious attempt to reform party funding, even after Ed Miliband voluntarily weakened Labour’s trade union links. The wealthy are still permitted to donate unlimited sums to political parties – and to be rewarded for doing so.

The independent-mindedness of Conservative MP Sarah Wollaston convinced Cameron to strangle open primaries at birth. His recalcitrant backbenches blocked House of Lords reform (an issue he had, in any case, described as a “third term priority”). The Recall Act, belatedly passed in 2015, vested power in a parliamentary committee, rather than the electorate. The old politics repeatedly trumped the new.

After achieving a majority, liberating him from the need to appease the Liberal Democrats, Cameron abandoned any pretence of progressive reform. Instead, he sought to use executive power to strengthen and entrench Tory rule: curbing the Lords’ rights, cutting public funding to opposition parties, diluting the Freedom of Information Act, imposing boundary changes and introducing the stunningly partisan Trade Union Bill.

Most of these changes were amended or abandoned as Cameron sought to curry favour with opponents before the EU referendum. But the intent was clear. In view of his record, it was entirely predictable that he would use the honours system in a tawdry and self-serving manner. Cameron is the man who stood by Andy Coulson (despite repeated and authoritative warnings), concealed his use of an offshore trust and gave his hairdresser an MBE in 2014.

A premiership that the public were promised would be different has ended in hackneyed style. Like Harold Wilson’s 1976 “Lavender List” (which was at least preceded by a referendum victory), history will record Cameron’s honours as a final stain. But the canvass was hardly clean to begin with.

Rarely has the honours system appeared more in need of reform. Whether or not Theresa May delivers to this end, we can say one thing with confidence: her heedless predecessor would never have done so.