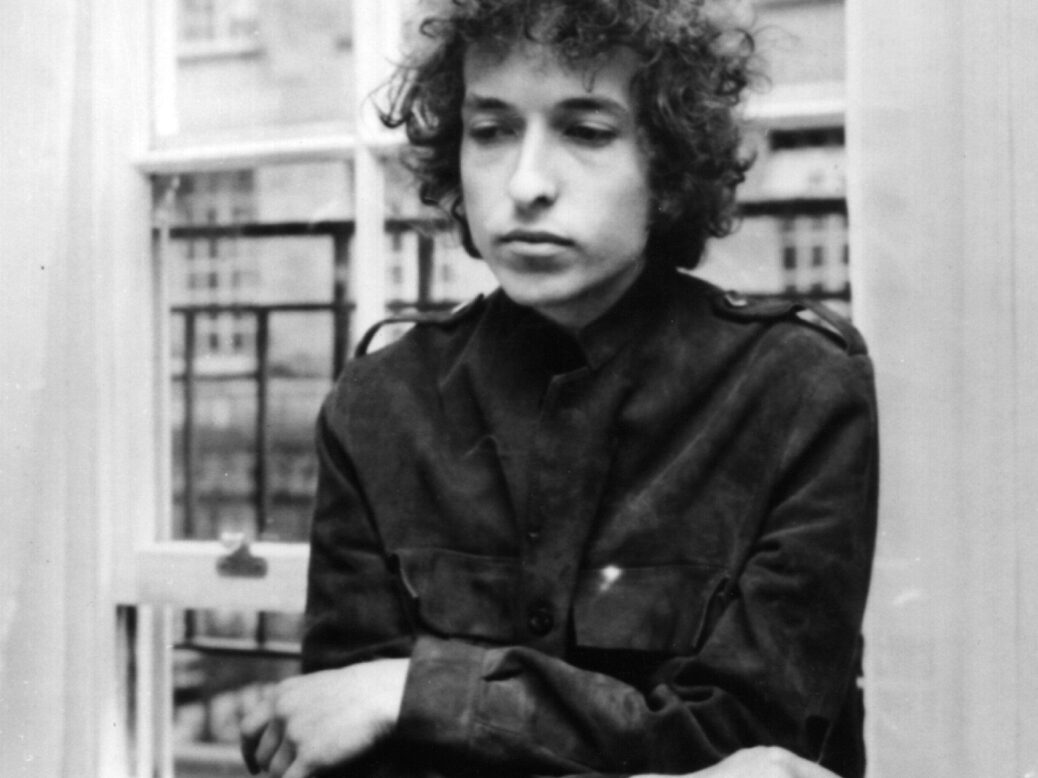

Bob Dylan in London in 1966. Photo: Express Newspapers/Getty

In 1987 I had just started working at NME. A collection of Byrds outtakes called Never Before came out. It was horrible. David Crosby had apparently got hold of the master tapes, pushed his voice way up in the mix, and – worse yet – added clattery Eighties drums to the recordings. I thought it was unlistenable, thought it may as well have been a Ben Liebrand remix, but deputy editor Danny Kelly – who I had, and have, the utmost respect for – didn t seem bothered: “I’ve waited so long just to hear these songs”, he reasoned.

You got what you were given in the olden days, when the music industry was fat. In 1975, CBS released Bob Dylan and the Band’s Basement Tapes, a selection of the legendary sessions recorded in a house called Big Pink in 1967. Coming across this album in the Eighties, I was confused by how Seventies they sounded, and nothing like the missing link I’d expected between Blonde On Blonde and John Wesley Harding. That was because Robbie Robertson had tampered with the originals, finishing them off, turning them into an album – “improving” them, I’m sure he thought.

The full set of Basement Tapes just issued by Sony – every variation, every scrap – is quite the opposite. The Basement Tapes were recorded over a whole year, a lifetime in Sixties pop, the difference between “Then He Kissed Me” and “You Really Got Me”, between “Drive My Car” and “Strawberry Fields Forever”, between “Barbara Ann” and “Good Vibrations”. It shouldn’t be a surprise that there are six discs’ worth of recordings; what is quite shocking is that Dylan allowed himself to be so entirely cut off from pop’s contemporary progression that there is no real aesthetic, melodic or structural difference between the music recorded in March ‘67 to that recorded in March ‘68.

Unlike almost everyone else recording pop music in 1967, Dylan cherished a means of escape more than a way forward. He wanted to know how to get out of being “Bob Dylan”, the prophet, seer and sage. Partly he worked this out by playing at being other people – John Lee Hooker on “Tupelo”, Johnny Cash on “Big River” – but the magic of this all-encompassing set is that you can hear Dylan and the group formerly known as the Hawks working together, at first tentatively, through all of their influences until, several months in, they hit a peak on originals like “This Wheel’s On Fire” and “Tears Of Rage”.

It goes something like this: disc one is made up of pussyfooting demos cut at Dylan’s home; disc two sees them messing about at Big Pink with a load of stoned covers (“See You Later Alligator” recast as a tribute to Allen Ginsberg); then suddenly on the third disc, their visions flow into one another – “This Wheel’s On Fire”, “I’m Not There”, “I Shall Be Released”. Midway through the fourth disc they revert to pissing about – blues jam “Get Your Rocks Off” makes “Rainy Day Women” sound deep, and “Bourbon Street” is dull enough to put you off touching another drop. A run through some of Dylan’s greatest hits on disc five (“Blowin’ In The Wind”, “It Ain’t Me Babe”, “One Too Many Mornings”) suggests the sessions had reached their natural conclusion (the final disc is made up of the poorest quality audio recordings that have survived), though it ends on an extraordinary high with the soulful, Curtis Mayfield-like “All You Have To Do Is Dream” and two deeply atmospheric tracks, “Goin’ To Acapulco” and the previously undocumented “Wild Wolf”. I’m no Dylan omnivore, but I imagine that for a true devotee, a brush with “Wild Wolf” would be like hearing “Tangled Up In Blue” for the first time.

The six-disc set comes with a hardback photo book containing Elliot Landy’s pictures that resulted in the Nashville Skyline cover, as well as intriguing paraphernalia like acetate labels, picture sleeves of cover versions by everyone from Julie Driscoll to Jonathan King, and press releases. Everything, in fact, except a song by song breakdown. For that, you need to buy the two-disc edited version, though this lacks the essential “Wild Wolf”, and – of course – it only talks about the highlighted songs. Sid Griffin’s main essay furrows my brow, too: of 1967, he says “The hit parade showed a popular music full of incense, peppermints, tea parties with the vicar, white rabbits, grandly orchestrated musical backdrops fraught with ruffles and flourishes.” This is the kind of conservative sniffiness that led to cat-calls when Dylan dared to introduce strings and black female backing singers on Self Portrait in 1970. Griffin’s notes use words like “truth” and “passion”, rather like Mark Hughes discussing Stoke City’s footballing philosophy. By 1967, he gasps, “even Buck Owens had bought a Moog synthesiser”. Good God! Where’s Pete Seeger’s axe when you need it? Call me a closet librarian, but I’d love to have an idea – even a rough one – of when the songs were recorded and in what order, rather than one man’s assassination of psychedelia and progressive pop. No matter. This is an essential, and surprisingly undersold, set.

It has always felt like something of a cop-out to say that the Velvet Underground’s third album is your favourite; it suggests you prefer the easy melodic charms of “Femme Fatale” to the abrasion and darkness of “Heroin”, or that the now-departed John Cale had been somehow problematic. Then again, you’re always going to get the grit and dissolution of “Waiting For The Man” on first listen – whatever terrors of loneliness might lurk behind Mo Tucker’s breezy barstool piece “After Hours” are more subtle but no less dark, nor is the album’s gently delivered opening couplet: “Candy says I’ve come to hate my body/And all that it requires in this world.”

The super-deluxe issue of The Velvet Underground’s eponymous third is another six-disc set, another major excavation, though it throws up less surprises and variation than The Basement Tapes. Here’s one thing, though – I might be very late to the party, but I never knew that there were two totally different takes on “Some Kinda Love”, depending on which pressing you owned. One has a characteristically bored sounding Lou Reed explaining how some kinds of love are “like a dirty French novel”, but the eager, breathing-in-your-ear version I knew from my mid-Eighties vinyl copy was apparently part of the rarer “closet mix” of the album. This is how the album was originally released, a version of the album on which Reed had pushed the vocals higher in the mix than they were on producer Val Valentin’s first attempt. There are no other alternate versions but the difference between the “Val Valentin Mix” and the “Closet Mix” is pronounced enough that both are given a disc each on this new set, as is a promotional mono mix.

The real treat for Velvets nuts is that the 1969 session tapes – the bulk of which were first issued as VU in 1985 – have been revisited on disc four. These fourteen songs would have been the basis of their fourth album had they not been dropped by incoming MGM president Mike Curb (he went on to become Republican Lieutenant Governor of California in 1979. Hardly surprising he dropped them, really). Like the ‘75 Basement Tapes, someone with clown gloves on had remixed these in ‘85 – for the first time we now get to hear “Foggy Notion” as it was originally mixed in 1969, without the perceptible mid-Eighties studio air that thinned out the VU version. Better still is a new mix of “I Can’t Stand It”, another one-chord wonder that was rendered unrecognisable as a product of the Sixties by an engineer whose guiding light was presumably Bob Clearmountain. The gated snare and orange-grey air of the VU mix is gone, leaving something that sounds rattier, but much more in keeping with late ‘68.

It’s odd to note the influences coming through, post-Cale. “She’s My Best Friend” shares the vocal descent of the Beatles’ “All I Gotta Do”. Elsewhere, I hear the lust of Buster Brown’s” Fannie Mae” and, more surprising, the almost ghostly but very white and suburban harmonies of a trio called the Fleetwoods. One of the earliest covers on The Basement Tapes (and a surprise, given Dylan’s poo-pooing of Fifties teen pop) is the Fleetwoods’ 1959 US number one “Mr Blue”. There may have been a desire amongst both the Band and the Velvet Underground to cut through the undergrowth and find a clearing in 1968, but there was also the pull of music from their teenage years, not so long ago, when things seemed less complicated. The Fleetwoods as an influence – it’s a surprising, and very sweet coincidence.