If you believe that perfectionism has upsides, Thomas Curran, a psychologist at the London School of Economics, would like to disabuse you of this. When a job candidate tells an interviewer that their greatest flaw is their perfectionism, this is intended as a humblebrag: I’m an exacting workaholic, the interviewee is saying – if anything, I’m too good. Perfectionism, however, isn’t about high standards, it’s about impossible standards. Studies show that perfectionism doesn’t lead to higher achievement at school or at work. Instead, perfectionists are defensive and insecure, hampered by a fear of failure and an inability to celebrate their successes, and they are at high risk of burnout.

Curran’s first book, The Perfection Trap, argues that perfectionism is the defining condition of our era, the product of a culture that promotes insatiable consumption and a relentless quest for self-improvement. He identifies as a perfectionist himself, someone who has worked all hours to make it in academia but finds himself wondering what all this striving was for. Would he have been happier had he followed his father into the construction industry, “laying bricks for a living, marrying a local girl, owning a modest house”?

In 2017 Curran conducted a meta-analysis (a study of other studies) covering 40,000 students based in Britain, the US and Canada, which found that rates of perfectionism had risen substantially between 1989 and 2016. At the time he was a sports science lecturer at the University of Bath. The day after the paper was published, he began fielding hundreds of calls from international news outlets. His article became the most covered in the 113-year history of the academic journal Psychological Bulletin. He later gave a TED talk, which has now been viewed more than three million times online.

[See also: Are you mentally ill, or very unhappy? Psychiatrists can’t agree]

Curran believes the public response to his paper reinforces his argument that perfectionism has reached epidemic levels. A sceptic could counter that sometimes theories that feel intuitively true – such as the idea that the internet is killing our attention spans – are, on closer inspection, more complex. Psychologists have identified three forms of perfectionism. The self-oriented perfectionist lives according to their own impossible standards, the other-oriented perfectionist cannot tolerate imperfection in others and the socially-prescribed perfectionist believes that others demand perfection of them.

All three kinds can cause suffering, but socially-prescribed perfectionists fare worst of all: the trait is correlated with problems such as loneliness, low self-esteem and vulnerability to mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders and suicide. While Curran’s meta-analysis showed that students were scoring more highly on all forms of perfectionism, rates of socially prescribed perfectionism have risen exponentially since the Eighties. It’s a sign, Curran writes, that “society’s expectations are well beyond the capacity of most people to meet”.

Curran believes that perfectionism has been driving the youth mental health crisis. While poverty, trauma and discrimination are primary causes of distress and mental illness among young people, researchers have found that more advantaged young people in particular are suffering as a result of excessive pressure to succeed. Primed since childhood to excel in a competitive, test-based education system, they are terrified of the consequences of failure in an unequal, knowledge-based economy.

As a result, Curran argues, top universities have become hotbeds of perfectionism, filled with anxious and unhappy overachievers. Students still believe in meritocracy: they tell themselves that if they are good enough, they will succeed, and that if they fail they deserve to, but the truth is that in both the UK and the US social mobility is going backwards, and talent and a good work ethic won’t always pay.

Rates of depression and suicide among young people have risen dramatically in the US since 2008, the same year that rates of socially-prescribed perfectionism started skyrocketing, and one year after Apple released the first iPhone. Curran writes that the correlation between social media use and mental distress among young people, the subject of much research by the US psychologist Jean Twenge, “passes the smell test”: social media encourages people to seek social approval, in the form of likes or follows, and to emulate the perfect-looking lives of the influencers they admire. Of course, real life isn’t an Instagram story, and no one looks as good as their profile picture.

Facebook’s own research, leaked in 2021, found that one in three teen girls believed that Instagram worsened their body image, and that teens consistently reported that the photo app increased their anxiety and depression. Curran believes the problem is exacerbated by social media’s economic model. Companies such as Meta (which owns Facebook and Instagram) are funded by ad revenues from consumer companies that profit from users’ feelings of insecurity – scrolling through social media feeling bad about ourselves primes us to buy items we mistakenly believe will make us feel better.

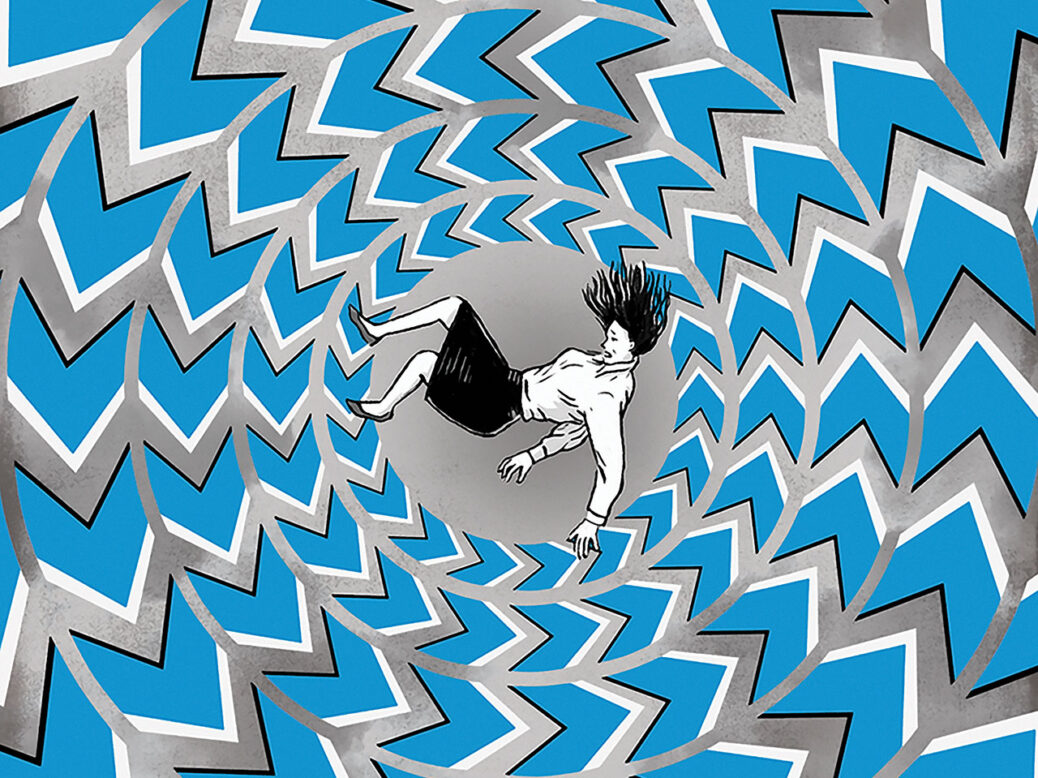

In fact, Curran argues, the biggest driver of perfectionism is consumer capitalism. “We’re living inside a hologram of unattainable perfection, with the imperative to constantly update our lives and lifestyles in search of a flawless nirvana that simply doesn’t exist,” he writes. The Perfection Trap begins as a fairly standard pop psychology book – with scientific studies interspersed with expert interviews and case studies presented as anonymised composites, such as social-media obsessed “Sarah”, and “Emma”, who dropped out of a corporate job to run a café – but it turns into something closer to a political manifesto.

[See also: Social media is taking a dangerous toll on teenage girls]

Perfectionism is not an individual problem, Curran argues, but a communal one. And so, while cultivating an attitude of self-acceptance may make living in a perfectionist world less painful, the real solution lies in political and economic reform. Countries need to stop pursuing unchecked economic growth, Curran writes, and must place national well-being over GDP. As jobs change in response to automation and AI, we need to carve out more leisure time for ourselves, while also reducing economic inequality through wealth taxes and universal basic income.

The problem with turning a self-help book into a political treatise is that some readers will already share your politics and think these are great ideas, but others won’t, in which case alleviating perfectionism seems like a pretty flimsy reason to completely change your views on the role of the state or the nature of the global economy. The political analysis is also fuzzy in parts. It’s unclear if Curran thinks that meritocracy is always bad, or if his problem is that Britain isn’t meritocratic enough.

He concerns himself mostly with self-oriented perfectionism and socially-oriented perfectionism, but what about other-oriented perfectionism? What is the effect of a ratings culture in which people – quick to leave one-star reviews for a hapless Uber driver or a hairdresser having a bad day – have punishing and impossible expectations of others?

Curran’s 2017 study resonated partly because we all have at least some perfectionist traits. Yet while reading The Perfection Trap it occurred to me that both self-oriented and socially-oriented perfectionism depend on considerable self-absorption, a preoccupation with your own achievements and how you are perceived, and that perhaps a way to break out of this pattern of thinking is to focus instead on your treatment of others. What would happen if rather than worrying about self-compassion, people devoted more time to thinking of how to better extend compassion and kindness to all the other imperfect, unhappy people trying their hardest to find contentment and meaning in an unequal, competitive and insatiable world?

The Perfection Trap: The Power of Good Enough in a World that Always Wants More

Thomas Curran

Cornerstone, 304pp, £22

[See also: How we misunderstand depression]

This article appears in the 07 Jun 2023 issue of the New Statesman, The Reeves Doctrine