On the eve of the 2016 US presidential election, the American author Curtis Sittenfeld published a short story called “The Nominee”, which inhabited the mind of a former first lady now running for president herself. “It’s strange how much I feel and cannot say,” Hillary Rodham Clinton – for it is she – confides to the reader as she submits to an interview by a combative female journalist at the time of the Democratic convention. It was a delicious, audacious, near real-time exercise in biographical fiction, teasing at the discrepancy between Clinton’s public, pantsuit-wearing persona and her real feelings. At a time when the whole world was looking at Hillary Clinton, here we were looking at the world with her.

By then, Sittenfeld – now 44 and the author of six novels plus the excellent short story collection, You Think It, I’ll Say It (2018) – had already established a reputation as a writer prepared to do a little psychological breaking-and-entering in service of her fiction. Back in 2008, she published American Wife, a thinly veiled “fiction” memoir about the former first lady, Laura Bush. In Sittenfeld’s version, her heroine is a book-smart woman who secretly disagrees with her husband’s policies but whose guilt-ridden early years help explain why she silently stood by him through his disastrous handling of the Iraq War.

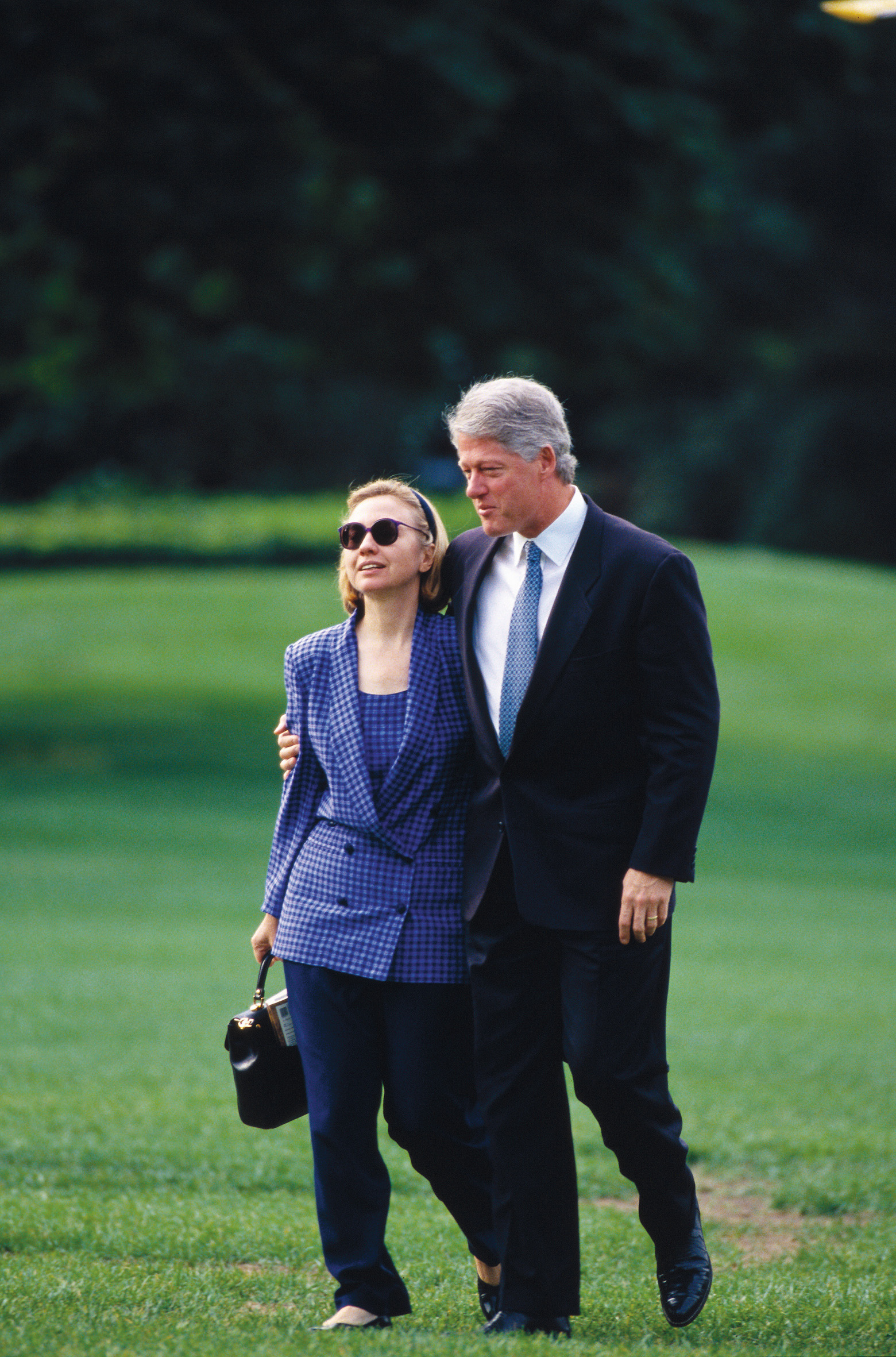

The novel, unfashionably sympathetic, became a surprise bestseller. But Hillary Clinton was always a more obvious choice for the Democrat-voting author. Sittenfeld has now returned to the defeated candidate. Again, she awards herself an all-access pass to Hillary’s mind – beginning when she’s a student – but while events in “The Nominee” could conceivably have happened, in the novel we are in a historical subjunctive, where after dating for four years, Hillary never married Bill Clinton. We can’t take anything from 1974 onwards for granted. “The present is the frailest of improbable constructs. It could have been very different,” as Ian McEwan wrote in his own recent counterfactual novel, Machines Like Me. Sittenfeld’s protagonist echoes that when she says: “really, it could have gone either way”.

The overall effect is very different from “The Nominee”. The short story was closer to a highly imaginative form of journalism than fiction. The question that kept you reading was: does this feel like Hillary? Reality provided the context. After the first third of Rodham, the context is fictional. Almost everything rests on how far you buy into Sittenfeld’s wayward, rather wistful vision of the past 40 years. The questions that keep you reading are hypotheticals: will this Bill and Hillary eventually wind up together? Will they make it to the White House – and, if so, in what order? But another question nags at the enterprise. Is this anything more than liberal wish-fulfilment – a chance to right not only the cosmic wrong of the 2016 election but everything leading up to it?

Rodham opens with an arresting prologue, in which diligent young Hillary delivers the first-ever student commencement speech at Wellesley College in 1969, a “bracing”, “idealistic” manifesto of “constructive protest” for a generation swept up in civil rights and anti-Vietnam War struggles. But the next 30 or so pages are stiff and flatfooted, cluttered with unnecessary detail about potluck dinners and legal aid work that sound plausibly earnest – but plausibly dull.

When Hillary meets Bill, the troubling idea that this is essentially fan-fiction began to enter my mind, Sittenfeld the ultimate Hillary stan. The pair flirt by reading out their CVs to one another. The attention of the swaggering, sax-playing Southerner unnerves the earnest Midwesterner. “It doesn’t make sense that someone like you wants to be the boyfriend of someone like me,” she tells him.

The story becomes more involving once Hillary and “handsome lion” Bill start to sleep with each other, though the fan-fic atmosphere still looms large in the lavish descriptions of her “intolerable ecstasy”. There are scenes of naked sax as he serenades her with marching songs. Sometimes the histrionics just about work: “Falling in love was shocking, shocking, utterly shocking.” But I suspect that Sittenfeld simply felt duty-bound to go there – “he blew on the mouthpiece and held his fingers over the buttons” – in order to add the sex scenes that all the memoirs and biographies missed out.

More interesting are the early intimations of Bill’s “simultaneity of appetites”. When the pair meet late at night in a diner, he dips French fries into her ice cream and, at the offer to retreat to her room, orders more food: “Wasn’t this moment about sexual tension rather than eating? But Bill, apparently, could be hungry for multiple things at once.” Their relationship is clearly fuelled by fierce intellectual connection but his libido soon becomes a problem, despite Hillary’s pragmatic attempts to develop a plan to deal with it (“strategising made me feel as close to him as sex”). She dutifully follows him to Arkansas – he sees the governorship as a springboard to the presidency – but here Sittenfeld starts playing loosey-goosey with the facts. Clinton’s philandering ultimately sends Rodham her own way.

We now skip forward to the early 1990s, where Hillary, an unmarried law professor at Northwestern, Chicago, is being courted by the Democrats to run for Senate. She’s a cautious, quick-witted professional, committed to public service – her only sin is to be caught up in a fraught but touchingly chaste affair with a married colleague. Scenes of sexual tension unfold as they watch the Senate hearings in which Anita Hill accused Supreme Court judge Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment. Meanwhile, Bill runs for the 1992 presidential race but drops out over similar allegations. In this version, his marriage to a simpering woman, rather than hard-headed, legally trained “equal”, is what radically changes the alignment of presidential history. Bill couldn’t have done it without Hillary.

Sittenfeld gives us a compelling account of the career Hillary might have had, complete with all the sexism and media chicanery she would have confronted on her path to the Oval Office. Among the real-life characters she encounters is Carol Moseley Braun, the first woman of colour to be elected to the Senate. In this version, Hillary doesn’t believe Moseley Braun is organised enough to seal a victory and runs against her, prompting some chewy reflections on racial equality.

It isn’t her only dirty decision (there’s another crucial one involving Donald Trump). But Sittenfeld comes out squarely in defence of her heroine as she weighs up the human longings and moral reckonings that lead to such political compromises. “Sometimes I think I’ve made so few mistakes that the public can remember all of them,” says Hillary, “in contrast to certain male politicians whose multitude of gaffes and transgressions gets jumbled in the collective imagination, either negated by one another or forgotten in the onslaught.” While Hillary still faces a hostile media, Sittenfeld suggests that without the added baggage of Bill, she is able to nimbly dodge any lingering scandal. Hillary could do it without Bill.

There is much to admire in Sittenfeld’s writing. Her ear is attuned to inconvenient truths and double standards, particularly misogyny in America. She specialises in awkward encounters and surprise shifts in power, and these elements feed into Hillary and Bill’s story, both true and alternate. Her characters are usually more slippery than they initially seem but secretly yearn to be unravelled, as we see in one memorably excruciating scene with the pair in their 50s.

But it’s hard to see how Rodham frames the events or issues in any new way – or wouldn’t have been more truthful reframed as fiction. It glimmers with relevance but doesn’t ever justify its need to be written.

“Rodham” is published in e-book and audio, and available to pre-order in hardback

Rodham: A Novel

Curtis Sittenfeld

Doubleday, 432pp, £16.99

This article appears in the 20 May 2020 issue of the New Statesman, The Great Moving Left Show