Genghis Khan: the Man Who Conquered the World

Frank McLynn

The Bodley Head, 646pp, £25

Saladin: the Life, the Legend and the Islamic Empire

John Man

Bantam Press, 287pp, £20

About three-quarters of the way through his compendious and thoughtful book, Frank McLynn pauses to wonder whether Genghis Khan might ever have considered calling a halt to his invasions. But what then would have become of his unpaid followers, who lived by pillaging the lands they conquered? Given the bare terrain and harsh climate of the steppe from which they had come, how could they possibly have been accommodated, had they returned home? And what, for that matter, did “home” mean to people so relentlessly mobile that they reckoned each man needed five horses if he was to live well? “Like the shark”, writes McLynn, “or Lewis Carroll’s Red Queen”, the Mongols could not but advance.

And advance they did, with a speed and efficiency that astonished. The ancient Scythians were “invincible”, Herodotus wrote, because they “have no cities: they shoot with bows from horseback; they live off herds of cattle, not from tillage, and their dwellings are on their wagons”. Fifteen hundred years later Genghis Khan led another nomadic people out of central Asia to prove him right.

As a boy, Genghis early demonstrated his ferocity and his resourcefulness. Hearing of the power of the Jin empire, he asked why, if the Chinese were so mighty, they bothered with trade. Why not take by force whatever they wanted? When his half-brother ate a fish he had caught, he shot him full of arrows. He was taken prisoner by a rival clan and disabled by a cangue – a horribly ingenious thing made of two heavy boards locked together around a man’s neck, and too wide for him to bring his hand to his mouth. In a cangue, most men starved. The 14-year-old future khan jumped into a river and, using his as a float, made his escape. Half a century later, still illiterate, still failing to see the point of peaceful coexistence with neighbouring peoples, he had made himself master of Asia from the China Sea to Bokhara.

McLynn offers a “sober estimate” of 37.5 million as the number of people for whose deaths Genghis Khan was responsible. Repeatedly he promised his opponents he would spare them, only to slaughter them once they had laid down their arms. He permitted his armies to loot and destroy great cities. After his victories, thousands of women were raped and thousands of men captured and used as a human shields in battle – being pushed to the front and killed by the arrows of his next opponent, allowing the Mongol horde to wait, unscathed, until the moment came for the decisive charge.

Genghis declared that he had been divinely appointed to rule the world, but his idea of the divinity was crudely utilitarian. Towards the end of his life he summoned a Chinese sage, Chang Chun. Chang set out reluctantly on a three-year journey, finally catching up with the conqueror near Kabul. He preached to him against drinking, hunting and sex. Genghis, who had female prisoners paraded before him after battle so that he could pick out the prettiest for himself, took little notice, and brusquely asked Chang for the elixir of life. When the sage told him there was no such thing he modified his demands. If not immortality, then couldn’t Chang and his disciples, “praying continually on my behalf”, at least procure him longevity? Yet his lack of interest in religious nuance made him tolerant, unlike his opponents. Christian, Buddhist, Confucian, Muslim, he slaughtered them all, but not for their faith.

What can we learn from this terrible man? The Mongols left no fine buildings, no artefacts. Their genius was for killing. They could fill the sky with a cloud of arrows while riding at full gallop, guiding their tough little horses with their legs, a skill that allowed them to conquer large parts of the world but whose only trace is one of ruined cities, burnt libraries and house-high pyramids of human skulls. Yet McLynn makes a case for Genghis as a brilliant political innovator. Archery and horsemanship, however prodigious, could not have made an empire, had it not been for the masterful way he reinvented Mongolia, transforming a chronically unstable society of warring clans into a unified and disciplined war machine.

The world in which he grew up was one of tribes riven by vendetta. There was a code of honour, but not one of social responsibility. Any man might become a clan leader, so every other aspirant to the position was his rival. Always on the move with their immense herds, the pastoralists became cattle rustlers, initiating yet more feuds. Punishment for disloyalty or betrayal was instant death. Blood was venerated, so the Mongols didn’t use their knives, preferring to strangle their victims or roll them in carpets and stomp on them until their backs broke.

Once Genghis had achieved dominance, he broke up the old loyalties, and the old hostilities, by a system that McLynn calls “supertribalism”, organising all Mongols into units of ten, then a hundred, then a thousand, all answerable to him. It was a military hierarchy for an aggressive new nation and it held together, even when its members were scattered across the Eurasian land mass, and despite the seismic changes he brought about when, thanks to conquests, the Mongols went in one lifetime from being a sheepskin-clad people, close to starvation by the end of each winter, to the recipients of enormous wealth, with silk on their backs and a tendency to get blind drunk on wine (four times as alcoholic as the fermented mare’s milk they had drunk for centuries). That he could impose his system on his unruly followers in the first place is remarkable. That he could make it hold is proof of his personal authority. McLynn, summing up his ghastly but compelling story, concludes that he was at once a “moral pygmy” and “the greatest conqueror of the ages”, a judgement that provokes thought about what we mean by “great”.

In 1221 two of his generals led their horde across the Caucasus, a test of endurance to rival Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps, making towards the Black Sea. There they encountered merchants of Venice who asked for their help against rivals from Genoa. A deal was done. The Mongols laid waste to a Genoese colony.

It was the Mongols’ first contact with a European power. It might have been expected to trigger a pan-European attempt to stop them but none followed. The Pope was looking elsewhere. Ignorant, or careless, of the infidel wolf pack sweeping towards his flock, he was busy slaughtering fellow Christians, the Albigensians, in southern France. Meanwhile, all over Europe, fighting men with a taste for booty and bloodshed in the service of Christendom took up arms, not to protect their own societies but to destroy the Islamic one that had gained control of Jerusalem. The crusaders, like Genghis, considered their aggression to be divinely sanctioned and, like Genghis, they grew rich far from home, in the Holy Land. There they encountered a warlord born a mere quarter-century before the Mongol world-bestrider – Saladin.

John Man, the author of Saladin, has written several books about the Mongols. Frank McLynn has written about Saladin’s most celebrated opponent, the English king Richard the Lionheart. The two historians have overlapping interests but very different approaches. McLynn’s notes and bibliography run to over a hundred pages, Man’s to barely ten. McLynn’s narrative is methodical and detailed. Its sentences are long, its arguments careful. Man’s feels flung together and is delivered in a chatty, laid-back style. One character meets “a nasty end”; another “fingers” a traitor after “the right sort of persuasion” (a euphemism for torture). McLynn’s tone is authoritative, Man’s that of an after-dinner raconteur.

The Sufis thought that God had sent Genghis Khan as a punishment for the decadent luxury of Shah Muhammad’s court. The scourge of Allah was also Allah’s instrument. The crusaders thought something similar of Saladin. They were fighting God’s battle. How could they lose? It must be because they had offended so grievously that God had sent this Muslim to chastise them. To explain to themselves the shocking fact that Jerusalem was once more in Muslim hands, they idealised their enemy. If Europeans underestimated Genghis Khan, they made a hero of Saladin.

Man’s sources are patchy. As he candidly declares, for Saladin’s first 26 years “we have no picture of him at all”. He fills the lacunae with information – variously quaint or illuminating – about carrier pigeons, long-distance horse-racing and the way warfare glutted the slave market.

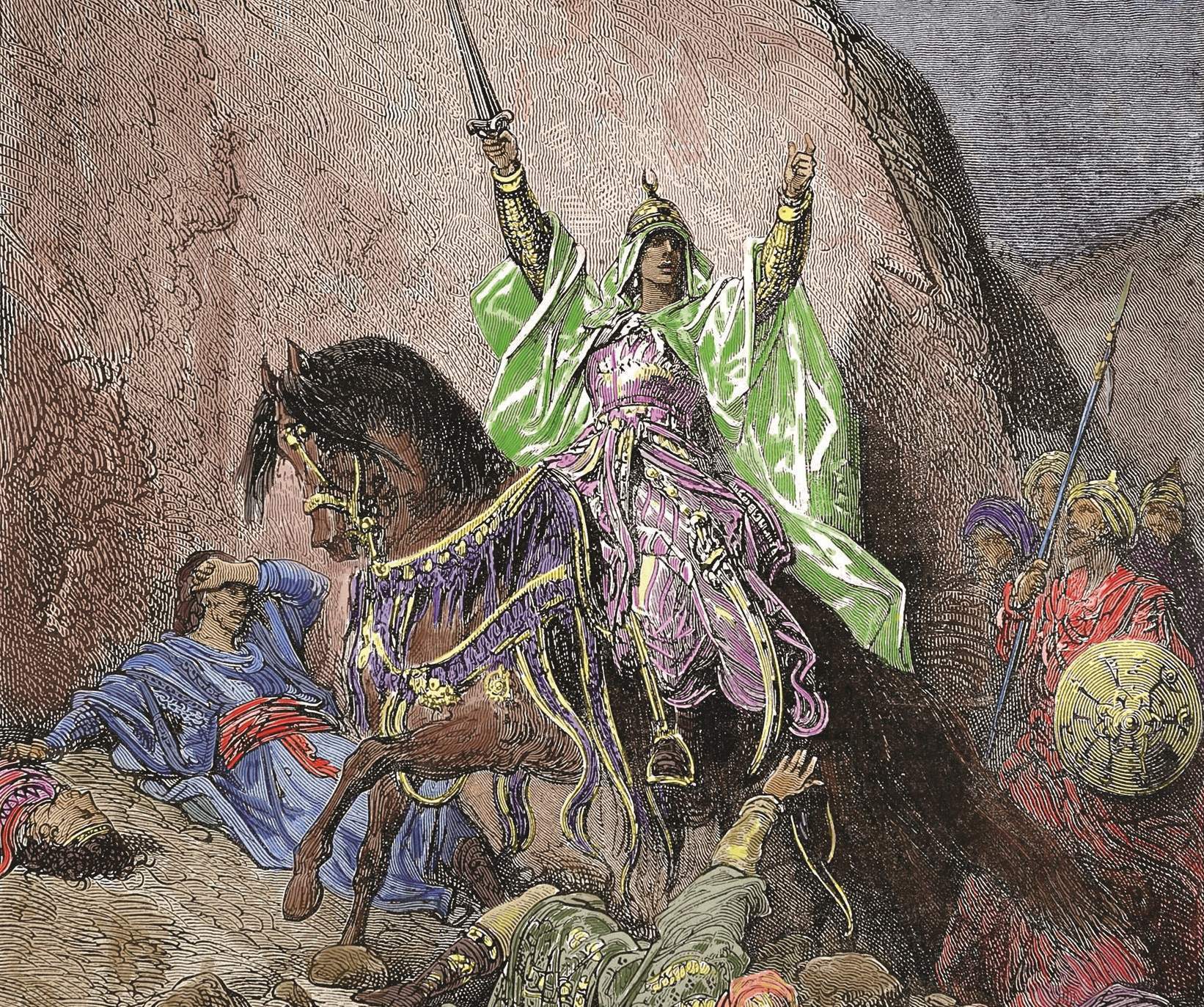

Saladin was ambitious, well connected and prompt to seize chances. When he was 30 he was appointed vizier of the Fatimid court. The sickly young caliph dying shortly thereafter, “Egypt fell into his lap”. At his induction ceremony it was said: “As for the jihad, thou art the nursling of its milk and the child of its bosom.” The presence of the Franks in Jerusalem was a provocation that it would be sinful to ignore.

As Genghis had subdued his fellow Mongols before setting out to subdue the world, so Saladin made himself paramount in his own region before taking on the infidels. When the sultan of Damascus died after a game of polo, Saladin, using Egyptian money, made himself master of Syria, too.

Man’s account of his rise to power is as confusing to the reader as it no doubt was to the participants. A castle burns, its Frankish commander leaping into the flames. In Baghdad, viziers are murdered. In Jerusalem the young king shows symptoms of leprosy. A wilful Frankish princess marries the wrong man, thereby jeopardising the succession. As Man writes, the Middle East is like a “nightmarish snooker table, with iron balls that are magnets of different strengths and sizes . . . sticking together in perverse alliances, and occasionally cannoning off into pockets labelled ‘death’ or ‘defeat’”.

Saladin picked his way adroitly through this deadly game. Man brings him at last to his great victory in 1187 at Hattin, and its aftermath, when he beheaded the rogue knight Reynald of Châtillon with his own hands and ordered the execution of 200 more. (This early champion of a pan-Islamic state based on Syria and Iraq seemed to his European contemporaries the very flower of chivalry, but he decapitated helpless prisoners as ruthlessly as his successors in Isis do now.) And so to Jerusalem. Saladin had announced that he would take it by the sword: “The men I will slaughter, and the women I will make slaves.” But he changed his mind. He needed money more than blood. He allowed Christians to buy their freedom, and so his reputation for mercy was formed.

The siege of Acre, Richard the Lionheart’s massacre of 2,600 prisoners of war, Saladin’s death: Man leads us through it all, a jovial guide full of quips and modern parallels. His only attempt to stand back and reflect on his subject comes in a perfunctory late chapter on leadership, with recycled comment from the Harvard Business Review and allusions to Winston Churchill. Sources from Saladin’s own era would surely have been more illuminating.

To understand the past we need not just a narrative of events, but also the re-creation of a lost mentality. Saladin captured the True Cross (a fragment of wood, set in gold and silver and borne aloft by Frankish bishops as they went into battle). After his death his son sent it to the caliph in Baghdad. It was stowed away somewhere. A few years later, as part of the peace treaty ending the Fifth Crusade, it was agreed that it should be returned to the Christians. But when the time came for its restitution, no one could find it. Removed from its context of faith and violence, the object for which so many crusaders had declared themselves ready to die was just a piece of glittering junk.