Future Days: Krautrock and the Building of Modern Germany

David Stubbs

Faber & Faber, 496pp, £20

As the seventh of Germany’s goals made their opponents’ net billow on that balmy July evening in Belo Horizonte – thus completing the humiliation of this year’s feted World Cup hosts, Brazil – and then a few days later, as the benign but steely alpha hausfrau Angela Merkel watched her boys lift the trophy, it was odd to reflect that at the end of the 1960s, while England swung and Brazil bossa-ed, Germany skulked, at least culturally.

Today, the Federal Republic of Germany is the world’s third-largest exporter behind China and the US and creates a quarter of the eurozone’s annual GDP. Yet, in the early 1970s, the economic miracle and Gerd Müller notwithstanding, it was still to an extent a nation in shadow; riven by terrorism, mistrust and a generational schism between parents who had grown up in Hitler’s Third Reich and children burdened with its toxic inheritance of shame.

Nowhere was this fracture seen more clearly than in the world of music. At the music school of Darmstadt and in the classical field, Karlheinz Stockhausen and his disciples were embracing a boldly experimental approach that overturned the cloying conservatism of the Nazis. And in popular music, whose practitioners were sometimes Stockhausen’s pupils and often emerged from the conservatoire, there was “Krautrock”.

Currently, Krautrock is a term that is bandied about alarmingly freely by bloggers, hipsters and, most of all, bands, desperate for its reflected cool. The latter will generally claim to have been immersing themselves in such 1970s German music during the making of their latest masterpiece, even if no one is quite sure what Krautrock means, or if indeed it means anything at all. As David Stubbs, in this first large-scale survey of the “movement”, neatly puts it: “Whenever a new group wish to show their experimental credentials, they will reach up and pick out the word ‘Krautrock’ like a condiment to add a radical dash to their press release.”

What this usually means is that they have appropriated the driving “Motorik” beat from the records of one particular act, Neu! – but, in truth, no two Krautrock acts sound remotely alike. Compare the dreamy synthesiser washes of Tangerine Dream with the alien noise collages of Faust or the psychedelic funk of Can. What Stubbs points out is that it was rather a modus operandi, a generational response to both the consumerist imperialism of the Marshall Plan and the US in their native land and the sins of their fathers and mothers.

The Third Reich looms large over Krautrock. Few bands or pieces address it directly but the ghost of it informs every riff and groove. Irmin Schmidt said that the loose, collectivist vibe of his band Can was down to a deliberate “no führers” policy. Stubbs smartly points out that when Frank Zappa goaded hippie audiences in the US by telling them that their schools were run by Nazis, he was being figurative and hyperbolic. For Can, Faust, Kraftwerk and the rest, it was literally true. Altnazis were still in positions of power in German social life, a tolerated stain on the national culture.

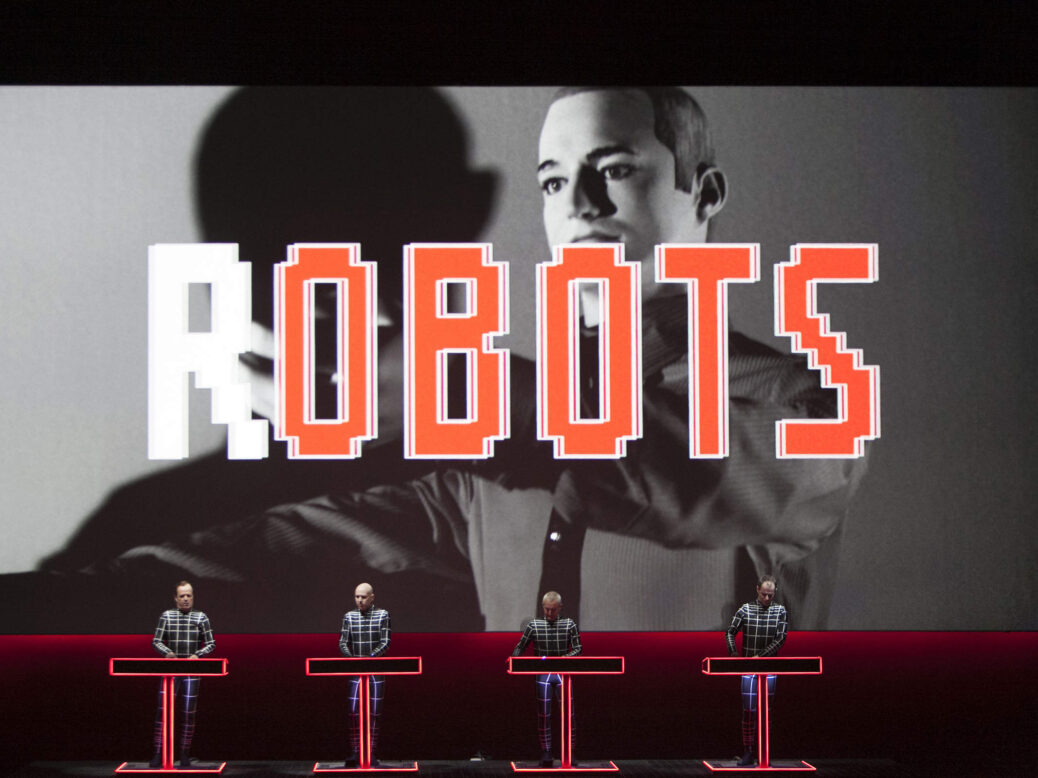

Stubbs is also good at placing this music in an economic and industrial context. “Invention, quite simply, is what Germans did. Industry and manufacture are key to the functioning of the German state,” he explains. “When Kraftwerk named themselves thus, the German word for ‘power plant’, they did so ironically but not scornfully . . . The Krautrock generation were born into a mostly prosperous, highly industrial society.” Kraftwerk addressed this most directly, with witty, tongue-in-cheek paeans to motorways, calculators and nuclear power stations. Like their peers, they did this in a way that owed little to the tropes of American or British rock.

The leading members of groups such as Can and Cluster were older than the Beatles and generally more influenced by Yoko Ono, or at least the Fluxus art movement of which she was a part. They belong to rock music but they are not entirely of it, more likely to have grown up immersed in musique concrète, Terry Riley and serialism than Little Richard or Elvis.

Krautrock is an uncomfortable term, not just conceptually debatable but crude – racist, even. Colin Newman of Wire, a band steeped in the German music of the era, says: “Germans have every reason to be offended by it.” John Weinzerl, a leading light of the movement with Amon Düül II, regards it as “criminal” and “insulting”. Stubbs argues that we would never describe a form of music as “Fagrock” or “Spaderock”. I’m not so sure, given the mores of the 1970s, but the point is taken. Some prefer the term “Kosmische Musik”, which is less inflammatory and even less meaningful. Stubbs reaches an uneasy truce with his conscience, considering the term to have been “semantically cleansed” to a degree.

In any event, the music coming out of the communes of Cologne and Munich and the academies of Düsseldorf and Berlin made small but significant inroads into British rock culture, thanks in no small degree to Virgin’s savvy releasing of albums such as The Faust Tapes for 49 pence. Tracks such as Kraftwerk’s “Europe Endless” helped relocate the hip cultural nexus of rock in the east to Berlin, Vienna and Paris, rather than Burbank, California, or New Jersey. Working-class Scottish punks such as Simple Minds and the Skids made records namechecking futurism and the Bauhaus. Eno collaborated with the German act Cluster and Bowie reshaped his oeuvre in the style of Neu! and Tangerine Dream.

The places where this survey comes closest to conventional rock journalism of the kind Stubbs grew up with – the swiping generalisations about music he isn’t keen on, the always doomed coloratura descriptions of music, the occasional crassness of expression – are weaker than the terrific narrative about nationhood and art, how the mainstream and the avant-garde cross-pollinate and how the aloof, addled and politicised young dropouts and eggheads of postwar Germany continue to influence Brits today who are making records in cities that the Luftwaffe once tried to shape and influence in a different way. Back in 1970, Melody Maker’s Richard Williams eulogised Krautrock bands thus: “Nobody in Britain is making this kind of music.” They are now.

Stuart Maconie’s latest book is “The People’s Songs: the Story of Modern Britain in 50 Songs” (Ebury, £9.99)