Friday brought the news that the government is going to be stepping up it’s alcohol strategy and moving beyond the previously discussed minimum pricing.

The Telegraph‘s James Kirkup wrote:

The Coalition’s alcohol strategy — expected to be launched next week — will propose that special deals which encourage shoppers to buy in bulk should be outlawed.

Most supermarkets offer significant discounts for customers buying bottles of wine by the dozen or half-dozen. Sainsbury’s and Waitrose, for example, regularly offer a 25 per cent discount for six bottles of wine.

Ministers believe such promotions give customers a financial incentive to purchase more alcohol than they intended to buy and should be banned.

The Telegraph takes umbrage with these plans, citing “fears that middle-class households will bear the brunt of measures supposedly aimed at troublemaking youths and other anti-social drinkers,” and while that is a distasteful way to put it – “middle-class households” and “anti-social drinkers” are not, and never have been, mutually exclusive – it touches upon a problem with expanding the scheme in this way.

Minimum pricing has had its supporters and detractors in these pages. George Eaton pointed out that it would hit the poorest hardest, Samira Shackle argued that “the evidence that alcohol consumption goes down when prices goes up is fairly strong”, and I explained why attempting to increase prices through the tax system alone was not likely to be effective. But the one thing which is universally agreed to be a benefit of the proposals is that it is blind to everything but price per unit. As a result, unlike the current duty laws – which impose different taxes on cider, beer, wine and spirits, even going so far as to distinguish “cider” from “high-strength cider” – it cannot help but applied most forcefully where it would have the most impact.

Clamping down on multi-buys, by contrast, may frequently lead to price rises which have very little impact at all on the amount drunk. It is hard to imagine a situation where someone picking up a four-for-three offer on bottles of Moët champagne is likely to become less of a problem drinker if that offer is scrapped.

While it’s not the most pressing concern – regardless of what the Telegraph says – it does mark out the transition of this policy package from a “hard”, evidence based, attempt to deal with problem drinking to a more populist attempt to make things look like they’re changing without doing that much.

Today we find that it may be that even minimum pricing – the part of the alcohol policy which has the most support of the medical community – is a busted flush. A new report from the Institute of Economic Affairs (pdf) takes a cross-national comparison of the effects of alcohol price on consumption – and focuses strongly on illicit consumption, with rates of both smuggled and home-made alcohol consumption rising.

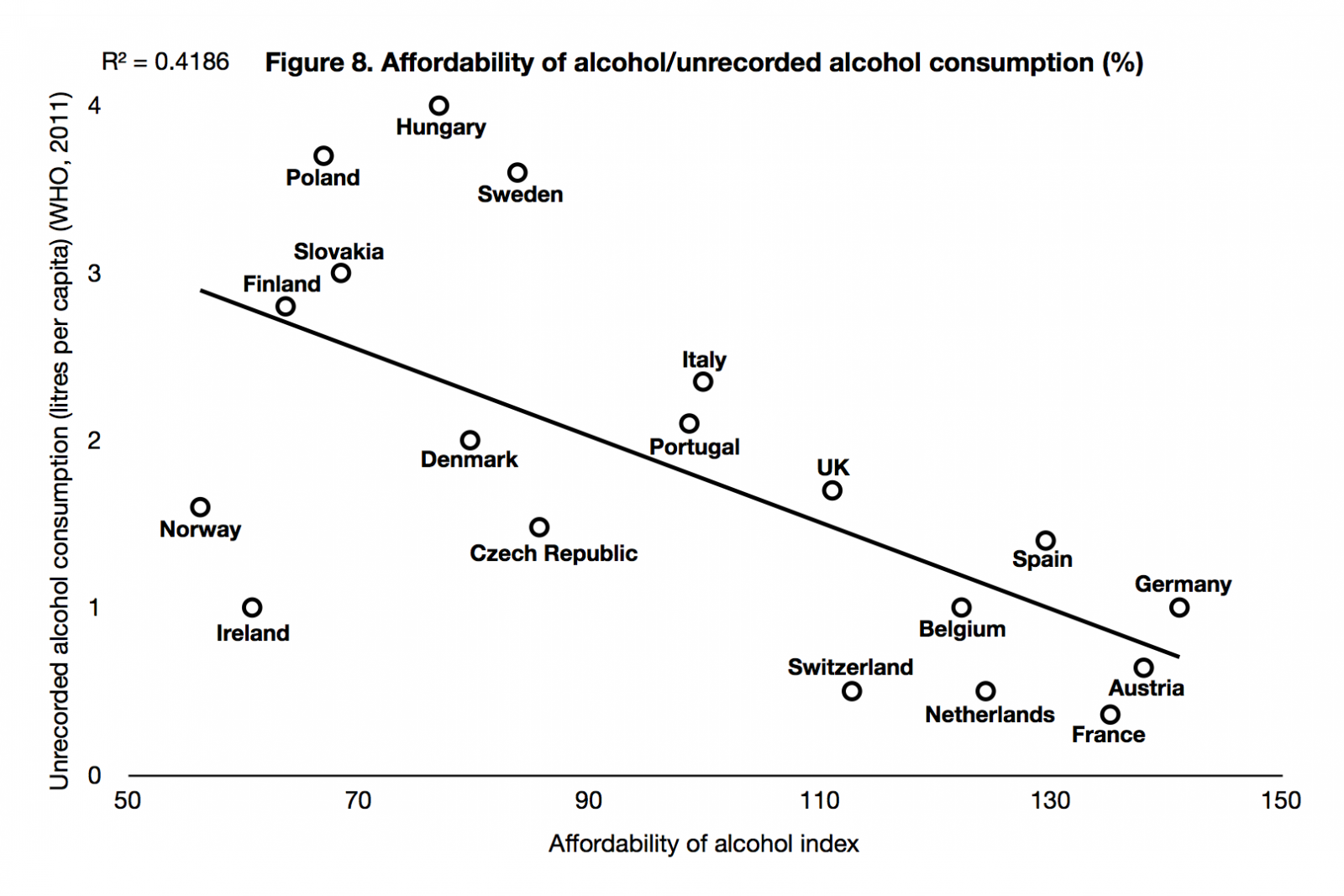

As you would expect, the more unaffordable alcohol is, the higher “unrecorded alcohol consumption” is estimated to be by the WHO, from around 3 litres per person in countries like Finland and Sweden, down to barely half a litre per person in France and Austria.

While the author, Christopher Snowdon, is keen to draw parallels with prohibition, citing John Stewart Mill’s claim that “to tax stimulants for the sole purpose of making them more difficult to be obtained is a measure differing only in degree from their entire prohibition, and would be justifiable only if that were justifiable,” it does seem that this “unrecorded alcohol consumption” is rarely as dangerous as bathtub gin. Although the stats are not presented, the more realistic inference – and Snowdon seems to agree, given his references to the geography of the countries involved – is that this unrecorded consumption consists mainly of cross-border sales, especially in richer countries. Not only is this not particularly dangerous, it isn’t even really smuggling, given almost all of the countries in the study are within the EU and thus have no requirement to pay duty or declare personal imports.

While it may not be dangerous, this unrecorded consumption adds to the key finding of Snowdon’s paper: the total absence of a cross-national correlation between affordability and consumption of alcohol.

Clearly, this all plays back into the debate around minimum pricing. Although Snowdon brings up the risk that minimum pricing encourages moonshine production, and so may even harm health, it’s not really important to overreach in that manner.

The key problem for advocates of minimum pricing si that if alcohol price is as poorly correlated with consumption as the above chart shows, then raising it may not do much for public health at all – while still having a strong negative effect on the private purse.

There’s still a lot to be said in this debate – not least because an IEA paper, no matter how good, struggles when pitted against a Lancet paper which concludes that (pdf):

Natural experiments in Europe consequent to economic treaties have shown that as alcohol taxes and prices were lowered, so sales, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related harm have usually increased.

But the argument is far from settled. It may be better if the government just backs off on the whole plan for a while.