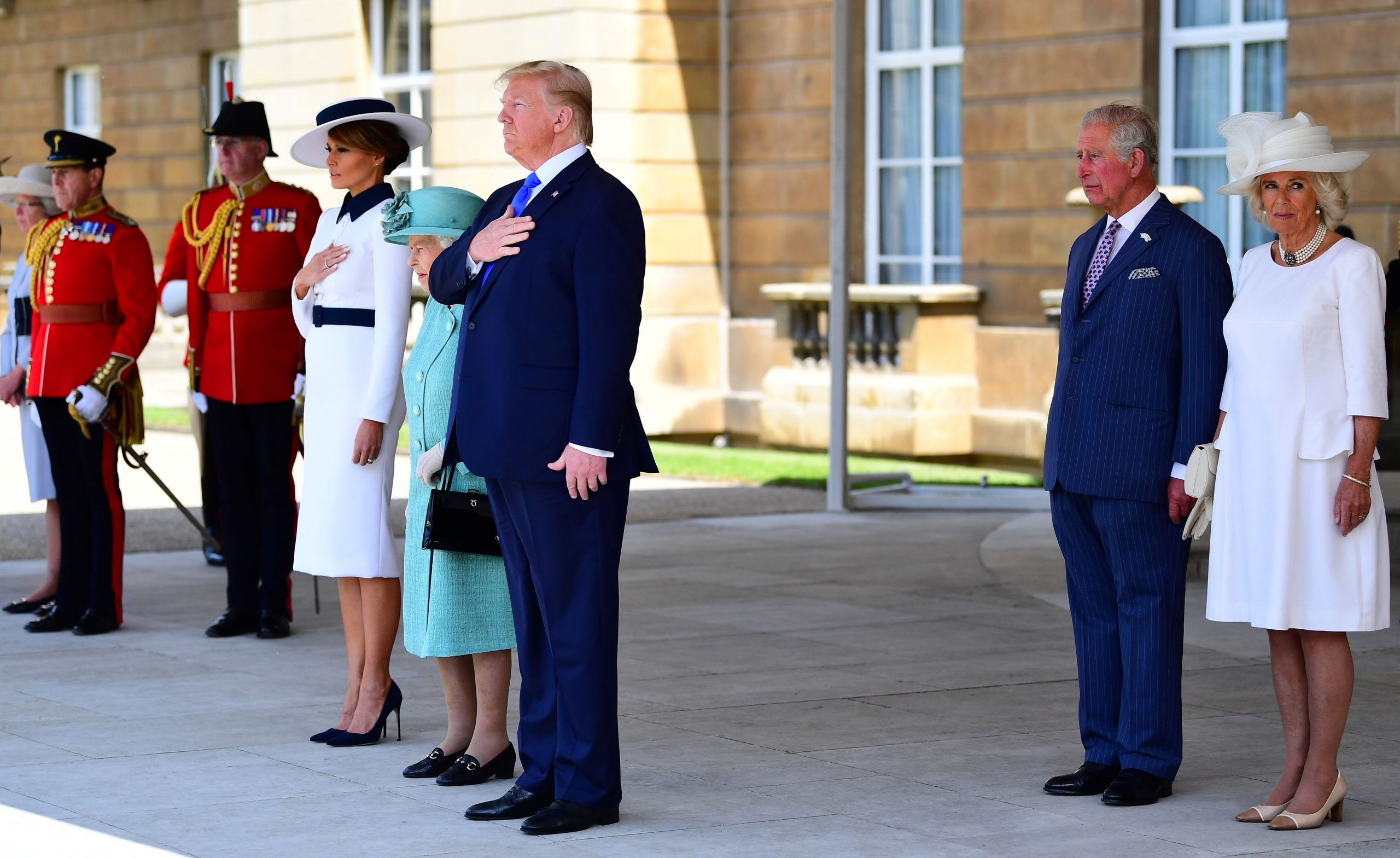

The photos of Donald Trump’s arrival at Buckingham Palace convey the impression – nauseating to those who consider him a liar, a cheat, a bigot, a threat to American democracy – that the president is currently a man completely in his element. That all he ever wanted was to stand next to the Queen on the steps of the palace inspecting the guard of honour in front of the world’s media, his chin raised high, his face puckered with pride and self-satisfaction.

That’s not quite right though. When Trump ran for the US presidency he wanted more than to be the guest of honour in royal households. He wanted to be treated as a royal himself. With every passing month it is becoming clearer that Trump never wanted to be president of the United States. He wanted to be king.

His love for royal pomp and ceremony is part of it, of course. Trump rarely smiles, but he seems happiest when presiding over a military parade or some other ceremonial event. What a blow it must have been for him to have to call off his planned Veterans Day military parade last year because of the estimated $90m bill, especially when his frenemy Kim Jong-un is never asked to account for the costs of his high-camp displays of military might and when the British royal family, though more constrained financially, is required to do nothing more than show up for such fancy ceremonies. As far as Trump is concerned, the Queen gets all the perks of high office with so few inconveniences – when was the last time anyone sniped about her not reading boring snoring briefing papers?

Last year, during the UN General Assembly, I ended up stuck behind a road block as the presidential convoy sped from the UN building to Trump Tower. When he looked through his car window at the mass of grumpy New Yorkers forced to a standstill, some recording the event on their mobile phones but most cursing him for making them run late, the president wore the same smug, aloof expression as on the steps of Buckingham Palace.

Trump always wanted the kind of power that money alone can’t buy. The huge police escorts; the ability to bring an international city, better still his hometown, to a halt; the adoring crowds – though his political rallies might seem a poor substitute for the spontaneous, crazed affection of British royalists who stockpile royal wedding memorabilia, or camp outside the palace dressed head-to-toe in union jacks or post teddy bears to baby Archie. The reason, after all, that Trump lied so outrageously and so transparently about the size of his inauguration crowd was because it mattered so much to him: his politics was only ever motivated by a desire for self-aggrandisement, for fame, followers and public recognition.

Trump no doubt envies the reverence with which the Queen is treated by both the British elites and the media. The New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik describes a seminal moment, during the 2011 White House Correspondents’ Association dinner when Barack Obama roasted Trump. He writes:

“Trump’s humiliation was as absolute, and as visible, as any I have ever seen: his head set in place, like a man in a pillory, he barely moved or altered his expression as wave after wave of laughter struck him. There was not a trace of feigning good humor about him, not an ounce of the normal politician’s, or American regular guy’s “Hey, good one on me!” attitude—that thick-skinned cheerfulness that almost all American public people learn, however painfully, to cultivate. No head bobbing or hand-clapping or chin-shaking or sheepish grinning—he sat perfectly still, chin tight, in locked, unmovable rage…

One can’t help but suspect that, on that night, Trump’s own sense of public humiliation became so overwhelming that he decided, perhaps at first unconsciously, that he would, somehow, get his own back—perhaps even pursue the Presidency after all, no matter how nihilistically or absurdly, and redeem himself.”

Trump, one could conclude, ran for president because he wanted to prove himself to the American political and business elites who have always sneered at him – who have considered him too crass, too tacky, too dumb to be one of them, no matter how many buildings he bought, or (dubious) charitable foundations he set up, or exclusive golf clubs he ran. He wanted the presidency to confer on him the prestige, the unquestioned social superiority that comes with royalty. It must irk him that it doesn’t.

Similarly, Trump’s fierce attacks on the press reveal his expectation that as president he should be treated with the same veneration the British media reserve for the royal family. He believes that he should be able to dictate the terms of his own media coverage, that his words should count for more than his deeds, that pillorying him should be taboo. He feels too that his position should accord him with the kind of international respectability enjoyed by the British royals, whose racist remarks or unsavoury friendships tend to be brushed off as faintly amusing, or just some British eccentricity.

Most disturbing of all, however, is Trump’s apparent belief that, like the Queen, his power should be protected from the public vote. His attempts to prepare for a strong 2020 Democratic challenger by already casting doubts on the legitimacy of the election process suggests the alarming possibility that if he loses the election next year he may not accept the result. If Trump had his way, he’d be allowed to stay in power until he chose to abdicate.

To know that Trump might be nursing a sense of jealousy and resentment during his tour of Buckingham Palace and his schedule of royal tea parties and luncheons is hardly consolation for those Brits who believe he merits no red-carpet treatment. Instead it raises disturbing questions on both sides of the Atlantic: how best can we contain Trump’s monarchic ambitions? And what does it say about our attitude towards the British royal family that Trump envies it so much?