Rock music has never been short of people who turn from inspiring and empathetic personalities to awful caricatures of themselves. Usually, as odd is it might sound, it’s an innocent process: success breeds arrogance, arrogance begets contempt, and one ends up with a singer who was once of their crowd becoming obsessed only with maintaining their status as a star. Hence Greil Marcus’s withering assessment of Rod Stewart in 1980: “Once the most compassionate presence in music, he has become a bilious self-parody – and sells more records than ever.”

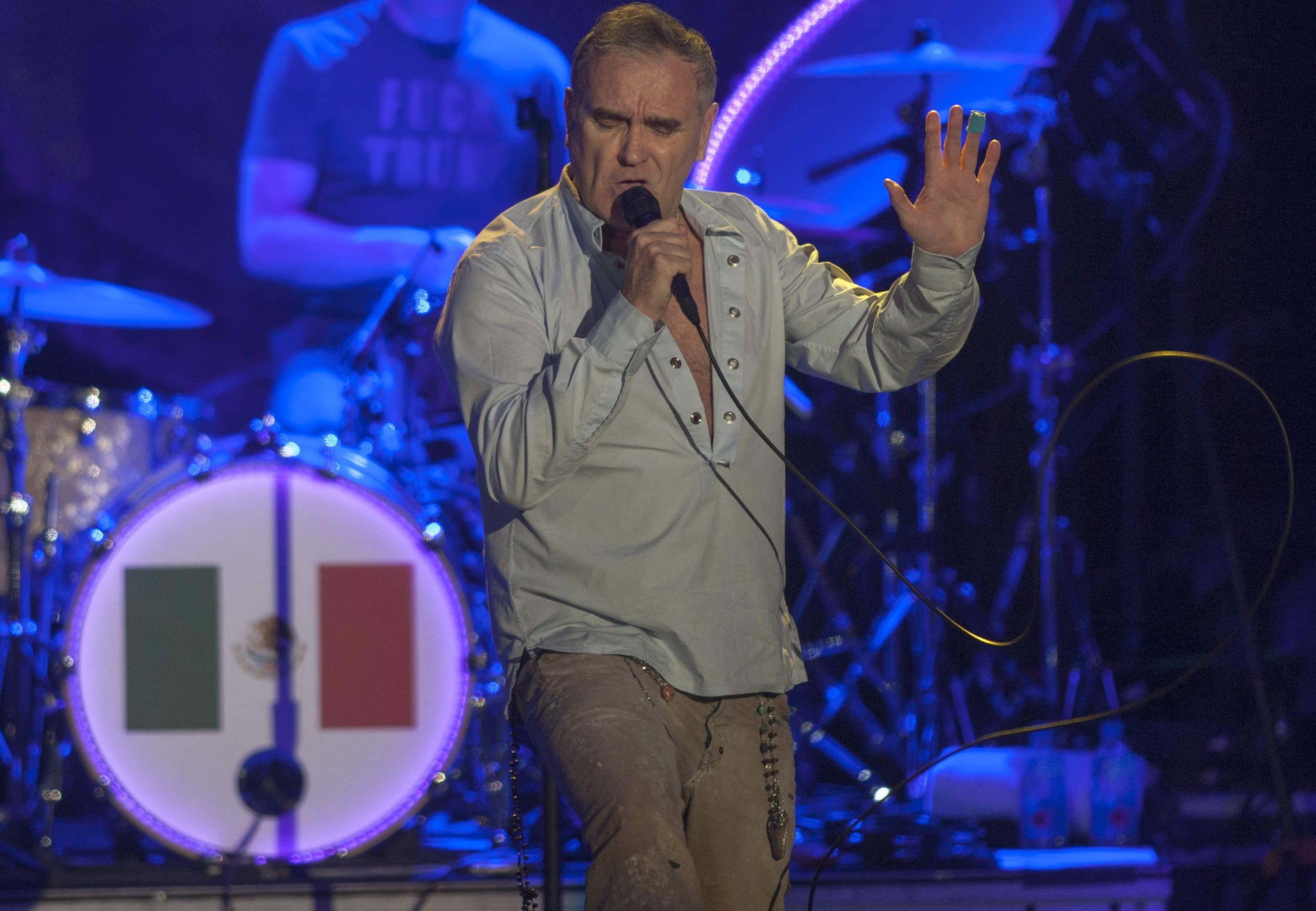

Few, though, have fallen as far from grace as Morrissey. The other week, BBC4’s repeats of old editions of Top of the Pops turned up the Smiths’ first appearance on the programme, performing This Charming Man in November 1983. Even more than 30 years on, it was impossible for those who were teenaged fans at the time not to feel our hearts leap a little at the strange creature on the screen, flailing about with gladioli in hand, offering up those bewitching opening lines: “Punctured bicycle, on a hillside desolate / Will nature make a man of me yet?” One felt the urge to turn and shush imaginary parents so attention could be paid, just as in 1983.

The Morrissey of the mid-80s was a decade or so older than most of his fans, young enough to remember what being teenaged was like, and he sang about it in terms no one had really managed: about the struggle to accept oneself, about not knowing how to speak to the object of one’s desire, about the loneliness of sitting in one’s room, wondering where there might be people who were young and alive. Morrissey understood us.

What the intervening years have proved, however, is that the only thing Morrissey understood was himself. His latest public intervention, a Facebook post on the Manchester Arena bombing, appeared to suggest immigration was to blame (the culprit was born in Manchester of immigrant parents, just like Morrissey), that politicians are never victims of terror (just shy of a year on from the murder of Jo Cox), that Sadiq Khan had not specifically named Isis in his condemnation of the killings, and that “in modern Britain everyone seems petrified to officially say what we all say in private.” Among those who approved of Morrissey’s views on the matter were Paul Joseph Watson, the British representative of Alex Jones’s extreme-right Info Wars conspiracy site and Milo Yiannopoulos, poster boy for those who believe bigotry to be a fun pastime.

Why be surprised? After Anders Breivik killed 77 people in Norway in 2011, Morrissey’s considered opinion on the matter was: “We all live in a murderous world, as the events in Norway have shown, with 97 [sic] dead. Though that is nothing compared to what happens in McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried shit every day.” There was his description of Chinese people as “a subspecies” in 2010. There were songs such as Bengali in Platforms (“Life is hard enough when you belong here”). There was his remark that to NME in 2007 that “If you walk down Knightsbridge you’ll be hard-pressed to hear anyone speaking English.”

So much for Morrissey’s politics. More distressing, perhaps, has been the way he talks of himself. Both his autobiography and his unrelentingly dreadful novel List of the List, hammered on about his personal bugbears, chief among which is his belief that he is the perpetual victim of everyone else’s venality. That has long governed his professional life, too, with his continual complaints about how record companies won’t touch him with a bargepole, because they’re run by people who despise him. For the record, the list of labels for which Morrissey has recorded music since leaving the Smiths is: HMV, Sire Records, Parlophone, Polydor, RCA Victor, Island, Mercury, Sanctuary Records, EMI, Reprise Records, Rhino, Decca Records, Harvest Records and Capitol. There are scores of people in senior positions at labels who adore Morrissey’s music, and know he will sell records for them. It’s not his music, or them, that is the problem; it’s him.

Morrissey turned 58 on Monday. You would never know that from his words, though. What is increasingly apparent is that back when he seemed so empathetic to teenagers, it wasn’t because he understood them, it was because he still thought like them: that he was the centre of a world that wouldn’t listen. You can get away with that when you’re in your 20s and your audience is teenagers. In your late 50s, when those original fans are in middle age themselves, you cannot. Hence Morrissey has become, to so many, a figure of mockery, or contempt, though he retains a large and loyal fanbase, many of whom subscribe to his view that he is the victim of evil forces rather than of his own solipsistic disregard for others. “Has the world changed, or have I changed?” he sang on The Queen Is Dead in 1986. The world changed, and he should have, too.

The records still sound marvellous, of course. Art does not wither. The man sounds less and less marvellous with each passing day. The old pun on a Smiths song title now seems closer to home and closer to the bone than ever: that bloke isn’t funny anymore.