“I felt I had no other option. The intravenous antibiotics weren’t working, I was so sick.” 29 year-old Ella Balasa has cystic fibrosis, a lung condition that means, among other things, she suffers regular infections by bacteria. Ella’s infections have become more severe over time, necessitating longer stays in hospital and stronger antibiotics as the bacteria became resistant.

Then, in 2019, she finally developed an infection that stopped responding to treatment altogether. “I was on intravenous antibiotics for five or six weeks and I wasn’t having any relief of my symptoms,” Ella said. Her lung function dropped to 18 percent and she was placed on supplementary oxygen.

A few months earlier, she had been contacted by the makers of a documentary about a cystic fibrosis patient in Texas treated with something called “phage” therapy. As someone who had a background in biology and worked in a lab, Ella was intrigued. “I had not really heard about phage therapy before,” she said, “they showed me the video and immediately I was like ‘I need this.’” She contacted the researchers at Yale working on phage and, after a one-week treatment course, she started to clear the infection, at a much faster rate than before.

Phages are viruses that only attack bacteria, by attaching themselves to the bacteria’s receptors. Each phage has a specific bacteria that it attaches to and kills, which means if you can find the right one it can be used to treat an infection resistant to antibiotics. Phages also lack the severe side-effects of stronger antibiotics. They’re not a new technology: phages were being used to treat infections already a century ago, but fell out of favour when antibiotics were discovered.

“The fact that phages are abundant in nature and the fact that they are specific makes them a very good alternative to antibiotics,” says Dr Antonia Sagona, an associate professor at the University of Warwick. There is still the possibility that bacteria become resistant to phages, she adds, but the phage viruses themselves evolve and adapt along with the bacteria. They can also be given in a cocktail alongside traditional antibiotics, and genetically modified to help counter resistance.

In the UK, however, regulations only allow phage therapy as a “last resort.” Given the treatment is also so specific and personalised, it is difficult to construct large-scale trials. In other countries, Dr Sagona explains, such as Belgium and the Netherlands, authorities are more open to using phages in a broader range of cases. Dr Sagona feels that the UK is quite regulated and cautious more generally in medical research, which makes it hard to develop more novel therapies. The UK has also traditionally invested heavily in the discovery of antibiotics, so there is a legacy there, she adds. “I am hoping that it [phage therapy] will be something that will be easier to approach and easier to approve compared to the situation now,” she said. “There is a big effort from the UK side to establish the regulations for phage therapy to be applied here,” Dr Sagona explained.

One specialist who has carried out phage treatment in the UK is Dr Helen Spencer, the lung transplant lead at Great Ormond Street Hospital. One of her cystic fibrosis patients had the same problem as Ella, an infection that was resistant to antibiotics and was shutting down their lungs. The infection recurred even after a lung transplant, placing the patient at high risk. “Most of those patients, if you get recurrence of infection, have died following transplant,” she explained.“ We knew we were in a pretty bad place.”

It was the patient’s mother who asked about whether phage therapy could be a possible treatment. By coincidence, one of Dr Spencer’s colleagues had done his PhD thesis on phage twenty years earlier, and he put in touch with a researcher in the US.

Professor Graham Hatfull describes himself as a “basic biologist” who has been working away at the science of phages at the University of Pittsburgh since the late 80s. It was only when Dr Spencer contacted them about her case that they got involved with the clinical side. “It’s a pretty dire situation for those patients out there who have got these types of infections for which the physicians really have little or no options,” he said. “Often the idea of using phages therapeutically is the last and only possibility for those patients.”

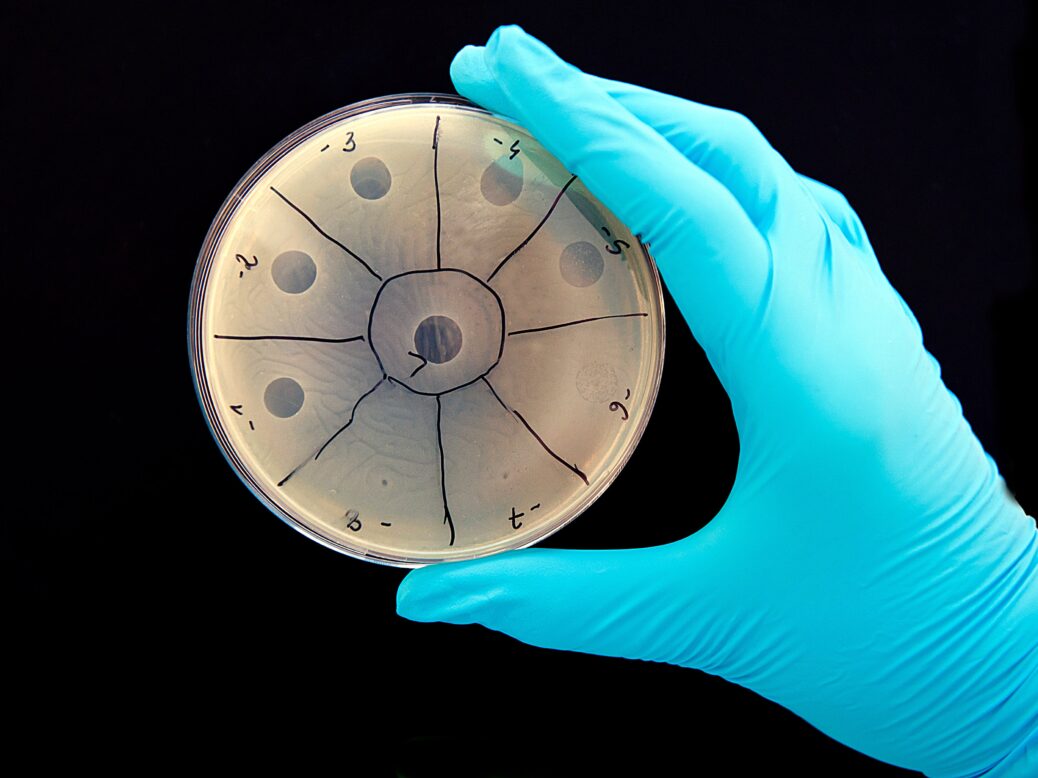

“Behind the scenes, Graham and his team in Pittsburgh were searching for phages and that took a couple of months,” Dr Spencer explained. The team screened thousands of phages and, using genetic modification, came up with a cocktail of three to use on the infection. It was just in time: by that point the patient had been sent home for palliative care alongside antibiotics.

Once they had agreed to go ahead, getting the phage across from Pittsburgh and approved for use took another twelve weeks before the patient could come in for treatment. “She tolerated it well,” Dr Spencer said. “To see her respond felt pretty miraculous at the time because all my other patients had died from this infection.” While her life has been extended, the infection still has not fully cleared and the team at Pittsburgh are continuing to work to find more phages to treat the infection.

Hatfull’s lab has since been contacted by around 200 clinicians working on cases where phage therapy might be an option. In each case, his lab test their phages to see if they will work on the specific bacteria, and they have been able to help on around 20 cases. However variation in the strains of bacteria means the phage that worked on the Great Ormond Street case is very unlikely to work on any other case. What Hatfull and his team are looking at now is whether it is possible to have a standard off-the-shelf phage treatment and how to get there from the almost personalised treatments that are being administered at present. The team is also yet to find a phage that works on the 40 percent of strains where colonies of bacteria are “smooth” as opposed to “rough,” Encouragingly, however, they are yet to see resistance emerging to phage therapy.

There is no risk of phages mutating to infect humans, assures Hatfull. “Phages have been around for probably around 3 billion years and we are exposed to them and we have phages in us all the time,” he explains. They are so specific, that it takes a huge amount of work to get phages to attack a broader set of strains of just one bacteria, so it’s highly unlikely it could “jump kingdoms” to even another species of bacteria, let alone humans.

“When Covid emerged, people realised the limitations of modern medicine. It’s a serious disease that there wasn’t a tablet for. The same for antimicrobial resistance,” says Dr Gordon Jamieson. “There we have a tablet, but the tablet’s going to stop working.”

Jamieson is chief commercial officer at Fixed Phage, a British company are essentially “phage hunters” who look at a problem, whether an infection or how to extend the shelf-life of a salad; look at which bacteria are at work, identify the phages that attack that bacteria and then work to “stabilise” it for use. The shelf-life of phages is often quite short, just a few days – not enough time for it to be transported and used – so Jamieson and his team have been working on extending that to a few months. Similarly, because phages are so specific to each type of bacteria, they too have to use “cocktails” of phages depending on how accurately the bacteria can be identified.

Dr Jamieson has found regulators “open to discussion” about use of phage because of the threat from antibiotic-resistant bacteria. However, the team still have to demonstrate safety, quality, and effectiveness. “There’s a little community of phage scientists and phage companies and what we’re all wanting to do is see more phage products out there, because then it creates the pathway,” he explains.

While Dr Jamieson acknowledges there are challenges and limitations, he is optimistic about the future of the technology. “It’s the same as electric cars or silicon chips, it’s one of those technologies you start somewhere and you’ve got to develop it, and once people get interested you can move mountains,” he said.

Ella still gets infections – it is a chronic part of her condition – and still has to take antibiotics, but feels that phages really worked for her, and believes longer and more frequent courses of treatment may help “beat back” the infections more. She has spoken widely about her experience and is active in pushing for new treatments for infections. “It’s the thing that affects my life the most,” she said.