It was just after 7pm. Yulia was lying on the sofa after a long day at work, trying to will herself to get up to make dinner. She made it approximately two steps before the first missile hit. The glass in the windows exploded. She felt the building shake. “It was surreal,” she said. She understood what was happening and could not believe what was happening at exactly the same time. She went downstairs to start helping people, but the police and the firefighters were already there. Someone asked her to go back upstairs to check on an elderly woman, and she ran back inside. Then the second missile struck.

“The sound of the explosion was so loud,” Yulia told me later from her hospital bed. “Everything was falling down. The doors, the walls, the window frames. It looked like everything was crumbling. The smoke was so thick it was hard to breathe.” She held her breath and tried to find her way down the stairs. She felt the broken glass cutting into her feet. “Everything was like in a horror movie,” she said. “Everyone looked so unreal.” She saw a man she knew and shouted for help. “He lifted me up and carried me as far away as possible.”

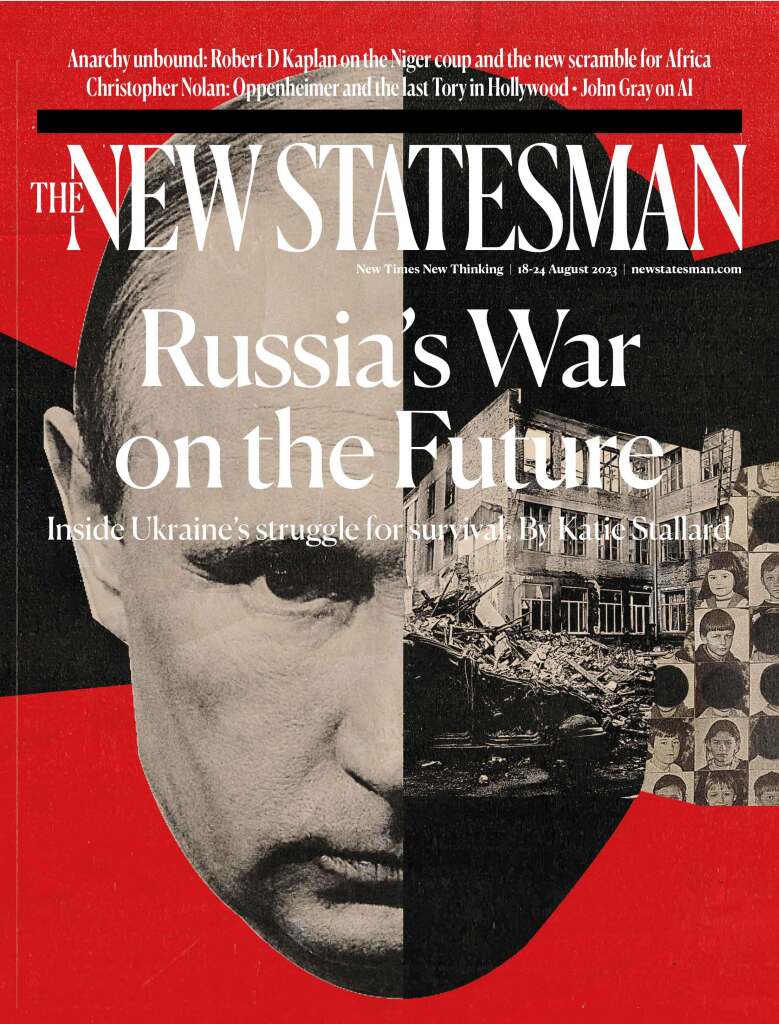

Pokrovsk is a small city in the Donetsk region of eastern Ukraine. This industrial heartland is where Vladimir Putin first launched his assault on the country in 2014, and it is where the heaviest battles of the current war are taking place. Pokrovsk is 50km from the front line and Yulia thought it was relatively safe. (Like everyone else I spoke to in the city, she asked me to use just her first name.) But this conflict is not only being fought on the battlefields. Putin is waging a war against Ukraine’s civilians too. This is a war on Ukraine’s future – a barbaric attempt to drag the country back into his imperialist fantasy of the past. Targeting women and children, and terrorising cities such as Pokrovsk is part of the plan.

“This war finds you everywhere,” Yulia said, lifting up her bandaged feet and gesturing to the cuts and bruises on her legs and arms. She had opened a hair salon in the city – she showed me the scissors tattoo on her forearm – but now she wanted to leave as soon as possible. “I think it’s finished for me here,” she said. “I am going to build a new life for myself, but not in Ukraine.”

Russia claims that it destroyed a military command post in the city, but there is no evidence such a facility ever existed. Instead, two Iskander missiles destroyed a small hotel that was popular with aid workers, journalists and, occasionally, off-duty soldiers (though the hotel had been closed for five weeks), along with the neighbouring block of flats and a children’s playground. The morning after the strike, rescue teams were still working through the ruins, the air thick with smoke and concrete dust. A war crimes investigator took photographs. An old man named Dmitry searched the rubble for his cat.

The cruelty was not only that the missiles targeted civilians in the city centre, but that they also targeted the emergency services who came to help them. The second strike came 37 minutes after the first, at the height of the rescue effort, a tactic known as a “double tap” that Russia perfected in Syria.

“I ran there to help people,” said Nurlan, a 32-year-old police officer, standing on a street near the site of the attack. “I started giving first aid to an old lady and managed to get her into an ambulance, but then the second missile hit.” Both his legs were heavily bandaged, and his arm was in a sling. “I felt the shrapnel entering my body and I thought I would not survive.”

Another policeman used a tourniquet to stop the bleeding and he was rushed to the hospital. His brother, also a police officer, was pinned beneath the rubble in the second explosion and broke his collarbone. “They knew the rescue workers would come, and they waited for the moment when we would get there.”

In all, nine people were killed in the attack on 7 August, including the deputy head of the regional emergency service. At least 82 people, including two children and dozens of rescue workers, were wounded. It was sheer terrorism, Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky said later that day: “Russia is trying to leave only broken and scorched stones.”

[See also: Ukraine must go to war with itself]

I had travelled to Pokrovsk the day before the strike to meet Iryna Rybinkina, a British-Ukrainian doctor who transports ambulances and medical equipment to Ukraine through her charity Smart Medical Aid. After working as a consultant anaesthetist in the NHS, she had just moved her young family to New Zealand to start a cardiac fellowship when the war began. She resigned on day seven. “I just thought, how can I be here on this paradise island when missiles are hitting Kyiv?”

Rybinkina’s husband, who is Dutch, flew with their two children, then aged two and nine, to the Netherlands, and she travelled on to Ukraine. “We are living with a 9/11 here every day,” she told me. “We are fighting for every life, but the Russians are bombing civilians and hospitals. What are we supposed to do, throw tourniquets at them?”

There have been at least 1,014 strikes on Ukrainian hospitals and medical workers since the full-scale war began in February 2022. On average, there are two such attacks every day. According to a recent report by a group of Ukrainian and international experts, Russia is deliberately targeting medical facilities, including children’s hospitals and maternity clinics, in an attempt to degrade the country’s healthcare system.

“Putting a red cross on a vehicle here is putting a target on it,” Rybinkina said. “I’ve lost a lot of close friends.” She scrolled through the photos of destroyed ambulances on her phone, pointing out a gaping hole in one from a rocket-propelled grenade strike. “Now, when I can’t reach someone on the phone for a few days, I know that they might be dead.”

We were sitting outside a small wooden church in the grounds of a hospital where Rybinkina had just finished setting up a new resuscitation room. The equipment was designed to be run from a generator if, as often happened, they lost power. “You know, I don’t sleep naked any more,” she said. “If they find me under the rubble, I want to be covered up. So now I sleep in my clothes.”

Her main fear was that people outside Ukraine were starting to lose interest in the war. On a visit to the UK earlier this year, a well-meaning former colleague had asked her whether there was still shooting in Ukraine. “Sometimes it is not even news,” she said as she wiped tears from her eyes with the back of her hand. It never got easier to say goodbye to her own children. Her daughter sometimes asked her when she was leaving, “why other mummies go to work and come back every day, but you don’t”. When her children were older, she said, “I need to be able to tell them that Mummy did everything she could.”

After the missile strike, I messaged Rybinkina to check that she was safe, but got no response. The force of the explosion had ripped chunks of concrete from walls and shattered windows across a ten-block radius in the city. Cars had been crushed in the street. “Putin is trying to scare everyone here,” said Oleksandr, a 60-year-old man in a bright orange shirt who was shovelling broken glass into a bucket outside his block of flats. “He wants to drive people away and divide us. He is trying to destroy our future.”

The air raid sirens started, so we moved inside the stairwell. I heard the distant thud of the air defences. This was not Oleksandr’s first experience of Putin’s wars. He had lived in Donetsk, the regional capital, until the start of the war there in 2014, when Russian proxies seized control of the city and declared their own “People’s Republic”. He had moved to Pokrovsk, and his son and five-year-old grandson went to Mariupol, the southern port city that Russia captured in May 2022. “They passed through absolute hell,” Oleksandr told me. “Now the little boy asks his parents not to open the curtains because he is scared that the shells and bombs will come again.” It was ironic, he told me, that Putin had claimed to be saving Russian speakers like him from genocide in eastern Ukraine as his justification for starting this war. “This is the real genocide.”

Putin’s intentions in Ukraine are barely disguised. Unable to win on the battlefield, he is trying to pummel the civilian population into submission and to eradicate the Ukrainian identity. This includes the mass abduction of Ukrainian children, for which he and his children’s rights commissioner are now wanted by the International Criminal Court. Putin cannot tolerate the idea of a free and independent Ukraine. As a Russian guard who identified himself as an FSB captain told Ihor Bondarenko, a Ukrainian journalist who had been taken prisoner in Kherson last summer, “It’s very simple – we want you to be with us, or we will kill every one of you.”

“We are ready to keep struggling against these stupid monsters,” Oleksandr told me. “But we really hope the UK and the other Western countries will not turn away from us. Without their support, we will not be able to keep going.”

Pokrovsk’s maternity hospital is the only specialist facility still working in the region, although now with sandbags piled against the windows at the end of the corridor. Here I met 22-year-old Tanya, who was curled up in a hospital bed next to her newborn son, Artem. He was 11 hours old, with tiny white mittens and a little blue hat. “He is pretty great,” Tanya said, gently stroking his face with her finger. “He is eating a lot and getting stronger.”

“We hear the air raid sirens almost every day,” she continued. She told me she tried not to think about the war, “but sometimes it knocks at your door”. Around a month earlier, she had been about to take a bath in her flat, but as she put one foot into the water, a blast wave shook the building and blew open her balcony door. She had heard the sound of the missile strikes two days earlier too. “I was so scared,” she said. “I just felt so worried for my baby.”

Tanya’s mother, Svetlana, works as a midwife at the hospital. So many people had been wounded in the attack, she said, that staff from the maternity ward had helped care for them. “We joked with the policemen, telling them, do you know you are being treated by the gynaecology department?” The only thing she wanted for her grandson, she said, was peace. “I hope that he will never know this war.”

There were around 1,200 babies born every year at the hospital before the war. Now, with so many people having moved away, that number has roughly halved. But many more of those babies were being born prematurely. “The biggest reason is stress,” Elena, the deputy head of the department, told me as we sat in her meticulously ordered office. “There are missile attacks happening and everyone is scared. If you are pregnant, you are frightened for yourself, for your baby, for your husband. You don’t know what will happen next.”

I asked her whether seeing the new babies being born every day at the hospital gave her hope. “Do you want to know my honest answer?” she said. “I’m sad to say that I don’t feel hope. I don’t see the future here. We stay and do our jobs because we must do our duty and we can’t just leave, but my own children are already abroad.”

More than six million Ukrainians have fled the country since the start of the war, the majority of them women and children. (Most men aged 18 to 60 are not allowed to leave the country.) This includes around 2.8 million working-age women, according to research by the economist Alexander Isakov. If they do not come back, he has warned that Ukraine stands to lose around 10 per cent of its pre-war GDP.

“Russia has had more success so far with its economic war than its military war,” said Stanislav Zinchenko, the head of the Kyiv-based economic think tank GMK Centre. “For example, before the war, we were one of the top exporters of grain and the number one exporter of sunflower oil in the world. Now, who is at the top? Russia.”

Ukrainian exports of iron and steel were also suffering, he explained, with Russia deliberately targeting the country’s export infrastructure. “If Ukraine cannot export our grain, iron ore, and steel, we will lose 40 per cent of our existing GDP,” Zinchenko warned. “We will lose jobs, we will lose taxes, and it will be the end of the Ukrainian economy as we knew it. Of course, then the state will also not be able to afford the same expenses for fighting against Russia.”

I headed north out of Pokrovsk, past the roadside stalls selling watermelons and, incongruously, garden gnomes, towards Kramatorsk, an industrial city around 30km from the front line. Before the war, this was a bustling hub of approximately 150,000 people, but here too many have left and the broad central avenues in the city centre were all but deserted. There were trenches and machine gun emplacements along the side of the roads where the Ukrainian soldiers had prepared for bitter street fighting last year, but the most devastating attacks came from the air. A cluster bomb assault on the railway station in April 2022 killed 59 people, including seven children. In June of this year, a missile strike on a popular pizza restaurant killed the Ukrainian novelist Victoria Amelina, along with 12 others.

[See also: Death and literature in Ukraine]

The schools in Kramatorsk, like those in Pokrovsk, closed last year. The older children study online, but there was nothing for the younger children, so Anna, a mother of two, started offering English lessons to local kids from the bright front room of her apartment. “Human beings simply can’t live in the horror all the time,” she told me. “We have to do something, so I provide classes for the children four times a week.”

And then there are her own children: German, who is 14 and going through his awkward teenager phase, and Anya, a five-year-old with long blonde hair. It has been easier for her daughter to adapt, Anna said, because she doesn’t remember the time before the war. “There was a time in my life when I wished that I could give them a great education,” she said. “But when the war came, I lost my financial security, and I can’t give them what I wanted several years ago. Now I can only pray for them and wish them to be safe.”

I asked German how he was coping with virtual school. “It’s really annoying,” he said. “I miss my friends. I am really in love with maths, but now I don’t understand anything because it’s all online.” He missed being able to meet up with his classmates in the centre of town, but now it was too dangerous.

“Before the war, he went to volleyball, karate, chess and swimming,” Anna explained. “But now all his time is spent at home. He has some problems with his eyes, so we have to reduce the time he spends on the computer, but there is nothing else to do.” She asked Anya, who was playing with a magic water painting set, what was happening in Kramatorsk.

“War.”

“She understands it,” Anna said, “but in her little childish world, how does she see it? I don’t know.” She tried again. “Anichka, what does the war mean?”

“Bombs are flying,” the little girl said.

Back in Pokrovsk, a group of workers was painting the bridge over the railway tracks with a fresh coat of blue and yellow, a small act of defiance against Putin’s attempts to crush the Ukrainian identity. On the platform, two families were waiting with cardboard boxes and plastic bags to board the evacuation train to Dnipro in central Ukraine (the national railway company runs a free evacuation service from front-line areas every day). They were from Toretsk, a small town further east where there has been intense fighting. Two children had been killed by shelling recently, and a volunteer rescue service had driven them out in a minibus. “Maybe it wasn’t much,” said Oksana of what they had left behind. “But we didn’t want to leave our homes.”

She had two boys, Lev, nine, and Oleksandr, 11. I asked how much they understood about what was happening. “Everything,” she said. “They were born in 2012 and 2014 so they have only ever known the war.” They could recognise the sounds of the various munitions better than she could, she said, “which is shelling, which is tanks, what is going in and going out”. Standing beside her, the two boys mimicked the sounds – the “shhoooo… BOOM” sound of the missiles, and the heavy thunderclap of the artillery. “Show us the place where there is no shelling, where there are no bangs,” Oksana said, “and we will start again.”

A message flashed up on my phone from Iryna Rybinkina, the British-Ukrainian doctor. “I’m alive. All good.”

Life in Pokrovsk was hard enough before the latest attack. Just over 80,000 people lived here before the war, according to the regional military administration, but that number was down to around 26,000 by the end of last year. (Local officials insist that many are now coming back.) Like so many other communities in the Donbas it is primarily a mining town, with rows of modest, single-storey homes clustered around ageing, Soviet-era apartment blocks. There has been no drinking water since an earlier strike destroyed a pumping station, but the city’s most vulnerable residents still need care.

In a neat, whitewashed building, Maria welcomed me into the Mercy Centre – a day centre for children and young adults with special needs. An effervescent woman with bright blonde hair wearing a cream dress embroidered with red poppies, she proudly showed off the ride-on plastic cars and specialist walkers for the students and the new light table that had been donated by someone in Kyiv. The missile strike earlier in the week meant many families had kept their children at home, she explained. Only five students had come today. She introduced me to Zhenya, an 18-year-old with a serious demeanour and a yellow T-shirt that said, “Rock ’n’ Roll”. “He’s our philosopher,” she said. “He’s a really intelligent guy.”

“Sometimes I am scared by the noises, and I worry about the planes,” Zhenya told me. He said he had been thinking a lot lately about what job he would like to do when he was older, but it was hard to choose. “Actually, right now,” he said, “my dream is to go to Legoland.”

Maria did everything she could to keep things as normal as possible for the students inside the centre but said sometimes it was impossible to block out the war. “They get really frightened when they hear the sound of the shelling,” Maria said. “Sometimes they hide under the table.” She had been relentlessly cheerful all morning, at times bursting into song, but now she lowered her voice and spoke urgently. “Please tell the world about what is happening here,” she said. “We are a front-line city, and the war is very close, but we need to keep doing this work. If we don’t, who will?”

No one in Pokrovsk expects this war to end soon. The reports from the front lines further east are of heavy fighting and heavy casualties. The most optimistic scenarios I heard involved Putin’s sudden demise, but most people here are preparing for a long, gruelling war that will be measured in years, not months. There will be more terrible attacks on civilians. But the Russian president appears to have underestimated the people he is trying to destroy. Despite everything, Maria and many others like her are determined to keep going. “We are not ready to give up,” she said, “so please don’t give up on us.”

As she showed me out, she told me that her son was fighting near Bakhmut, where some of the fiercest battles are taking place. I asked her how he was, and her eyes filled with tears. “We believe in the Ukrainian army,” she said at last. “We believe in the victory. Everything will be Ukraine.”

[See also: “The guy I was before the Russian captured me has died”]

This article appears in the 16 Aug 2023 issue of the New Statesman, Russia’s War on the Future